Overclocking: Principles and Risks

You can make your CPU faster for free? The story of how I almost fried my CPU pushing past factory limits.

You can make your CPU faster for free? The story of how I almost fried my CPU pushing past factory limits.

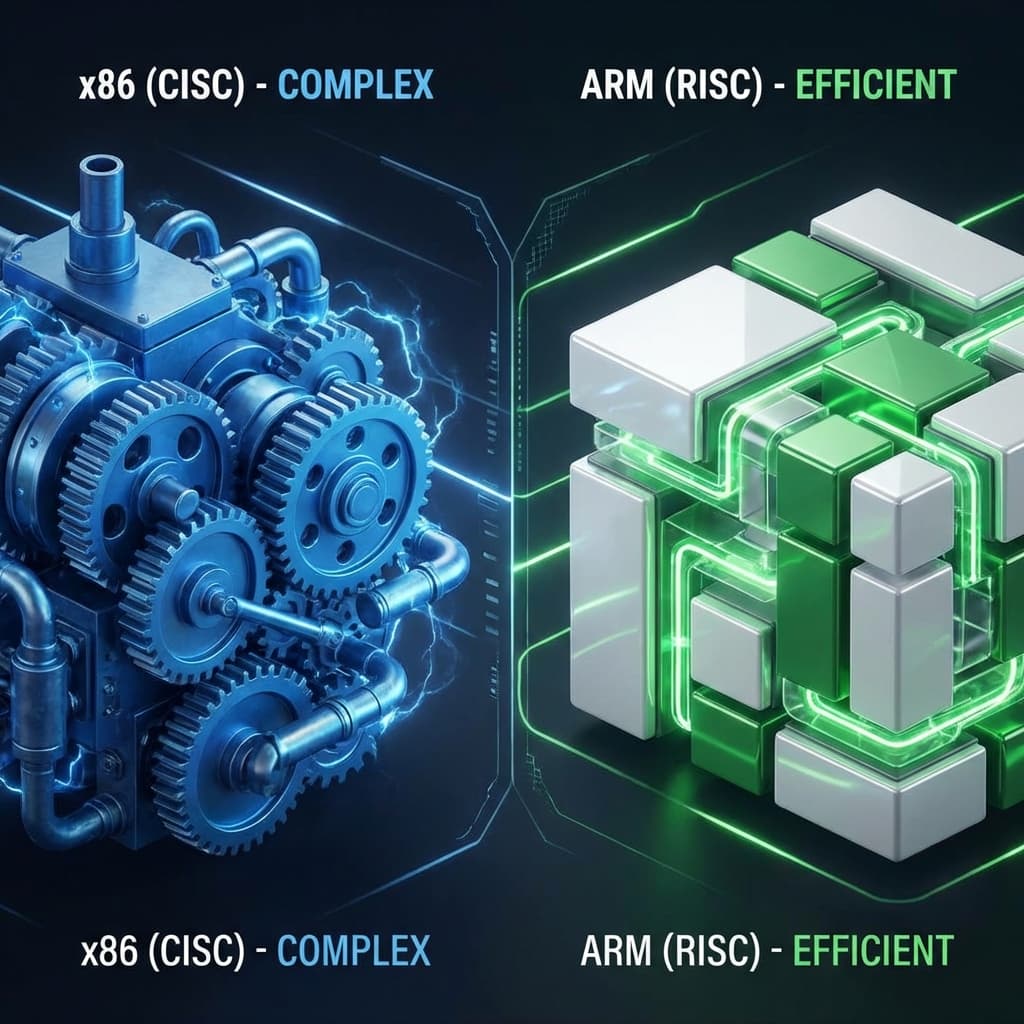

Why does MacBook battery last long? Should I use AWS Graviton? A deep dive into the philosophy of CISC (Complex) vs RISC (Simple) architectures.

The gold mine of AI era, NVIDIA GPUs. Why do we run AI on gaming graphics cards? Learn the difference between workers (CUDA) and matrix geniuses (Tensor Cores).

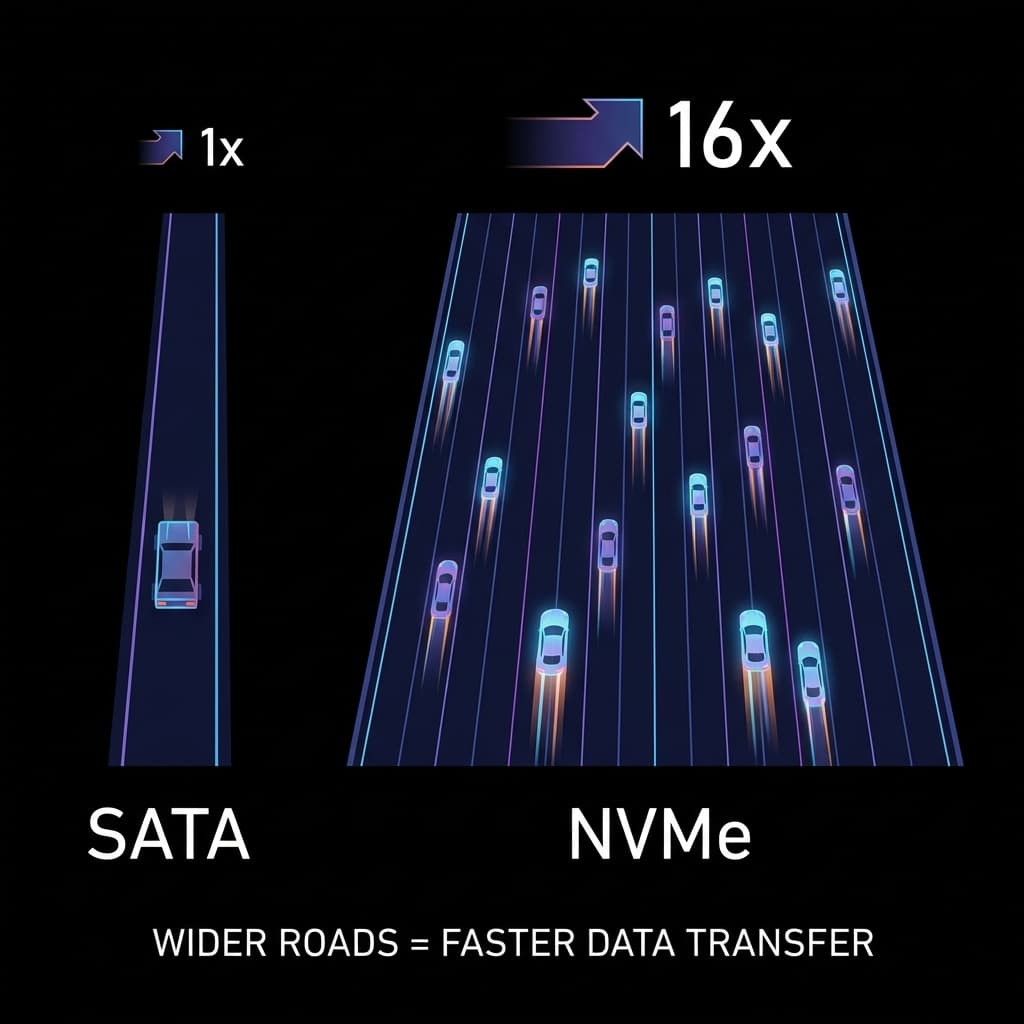

Bought a fast SSD but it's still slow? One-lane country road (SATA) vs 16-lane highway (NVMe).

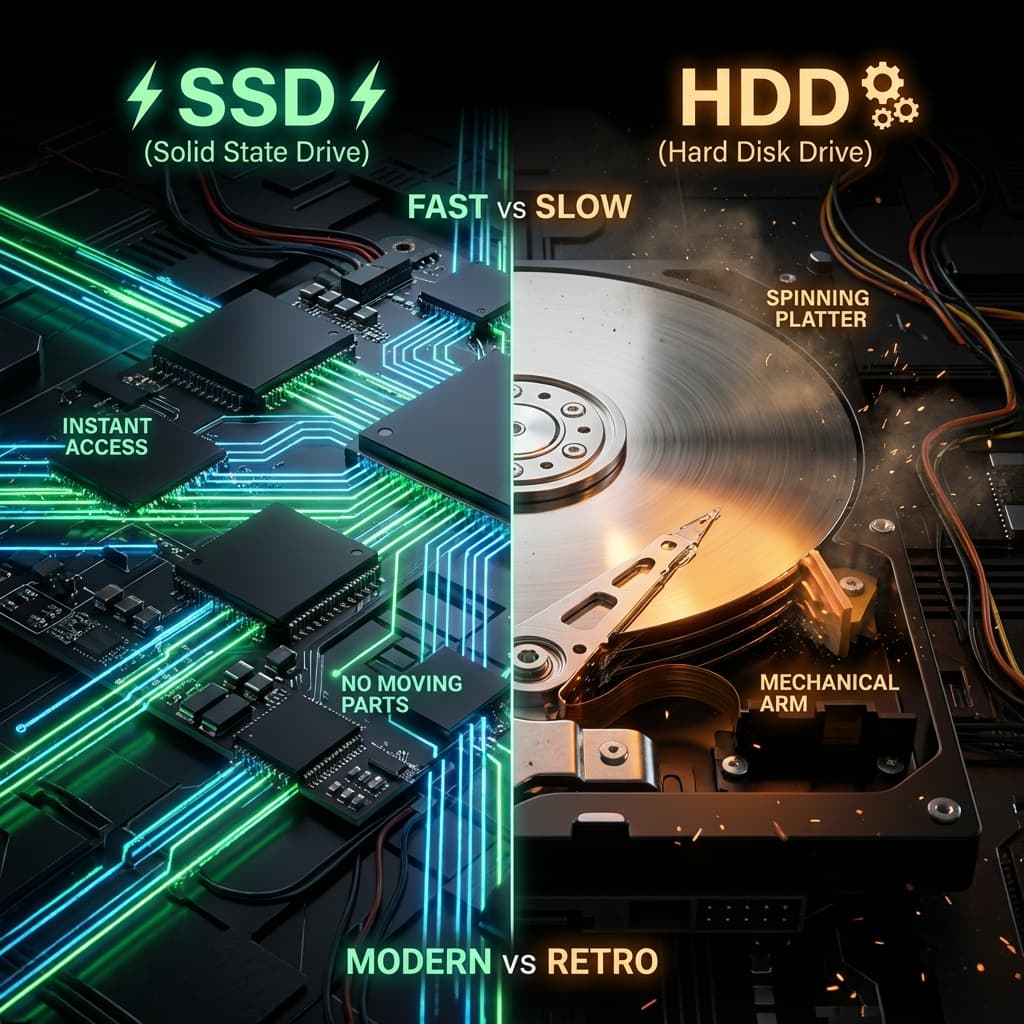

LP records vs USB drives. Why physically spinning disks are inherently slow, and how SSDs made servers 100x faster.

When I first built my PC, I heard this tempting rumor: "Just do a basic overclock, and you get 10% more performance for free." My ears perked up. Getting the performance of a more expensive CPU without spending a dime? This seemed like a no-brainer.

I had bought an i5-9600K, and I read online that "K-series CPUs are unlocked for overclocking." What's so special about the K suffix? Curious, I entered the BIOS and started tweaking numbers.

I bumped it from 3.7GHz to 4.0GHz. Reboot. It worked! Then I pushed it to 4.3GHz. Reboot. Still running! So I got greedy. I cranked it up to 4.6GHz.

10 minutes later, my screen turned blue. (BSOD) That's when I learned: "There is no such thing as a free lunch."

The best way I understood Overclocking was through the "Galley Ship" analogy.

At Base Clock, the drum beats at a reasonable pace. The rowers row rhythmically without exhausting themselves. The 3.7GHz speed is what Intel guarantees as "safe for all ships (CPUs) to sail."

But I (the user) want to go faster, so I start beating the drum frantically. (Increasing Clock Speed).

At first, the rowers struggle but keep up. The ship moves faster (Performance Boost). But if the beat gets too fast, rowers trip over each other, drop their oars, or faint from exhaustion. This is System Instability (Blue Screen).

What I learned here is that there are two ways to increase clock speed.

Base Clock (BCLK) is literally the 'base drumbeat.' It's usually fixed at 100MHz. The final CPU speed is calculated like this:

Final Speed = Base Clock × Multiplier

3.7GHz = 100MHz × 37

Touching the Base Clock affects not just the CPU, but also memory, PCIe, and even USB. It's like changing the fundamental rhythm. I avoided this method because it was too risky.

Most overclocking uses this method. The key feature of K-series CPUs is the "unlocked multiplier."

4.6GHz = 100MHz × 46

Keep the Base Clock at 100MHz, and only raise the multiplier from 37 to 46. This way, other components are unaffected, and only the CPU runs faster.

I understood this as "removing the factory speed limiter on a race car." The car can go 200km/h, but the factory limits it to 150km/h for safety. The K-series is a car where you can remove that limiter.

I raised the multiplier to 46, but I kept getting blue screens. I thought, "Isn't raising the clock enough?" But I was wrong.

The rowers wanted to keep up with the drumbeat, but they didn't have the stamina.So I increased the Voltage. The default CPU voltage is usually around 1.2V. I raised it to 1.25V.

It definitely worked. With more energy, they could sustain the faster beat. But a new problem arose. Eating more and working harder made them generate massive amounts of heat.

That's when I learned this scary formula:

Power Consumption = Voltage² × Frequency

If I raise the voltage from 1.2V to 1.3V (about 8% increase), the power consumption increases by 17%. That's because voltage is squared in the equation.

At first, I didn't understand. "Why doesn't it increase linearly? Why squared?" When I looked up electrical engineering concepts, I learned that Power = Voltage (V) × Current (I), and when you raise voltage, current also increases. So it becomes V × I = V × (V/R) = V²/R.

Understanding this formula explained "why overclocking increases my electricity bill."

When I raised the voltage, CPU temperatures shot up. I ran Prime95, a stress-testing program, and temperatures hit 90°C.

Suddenly, the clock speed dropped from 4.6GHz to 3.5GHz. This was Thermal Throttling.

CPUs have a self-protection mechanism. When temperatures get too high (usually 90~100°C), they automatically lower the clock to reduce heat. Like rowers threatening to go on strike because "it's too hot to work."

I monitored real-time temperatures using HWMonitor.

# On Linux, you can check with the sensors command

sensors

# Sample output:

coretemp-isa-0000

Adapter: ISA adapter

Package id 0: +92.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

Core 0: +91.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

Core 1: +93.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

As you can see, the package temperature hit 92°C. At this point, throttling kicks in.

So I installed a tower-style air cooler, and eventually, a liquid cooler. Liquid coolers circulate water to remove heat.

With the liquid cooler, the same 4.6GHz overclock kept temperatures around 75°C. Without throttling, performance stayed stable.

Finally, with the combo of "Fast Beat (High Clock) + More Food (High Voltage) + Strong Cooling (Good Cooler)", I succeeded.

I wondered, "Are Intel or AMD stupid? Why didn't they sell it at this speed from the start?" This question was answered when I learned about the 'Silicon Lottery' and 'Binning'.

Semiconductors aren't identical. Even chips stamped from the same wafer vary wildly in quality. Chips from the same wafer can have drastically different performance.

Intel or AMD tests each chip after stamping them from the wafer.

Testing Process:

1. Apply various voltages and clocks to each chip

2. Run stability tests (measure temperature, error rates)

3. Sort by performance (Binning)

Results:

- Top tier: i9 (can handle 5.0GHz+)

- High tier: i7 (can handle 4.5GHz+)

- Mid tier: i5 (can handle 4.0GHz+)

- Low tier: i3 (can handle 3.5GHz+)

What's shocking is that physically, these chips are nearly identical, but testing results determine whether it becomes an i3 or i9.

Manufacturers set the official spec to a speed where "even the weakest chip runs safely." This minimizes warranty claims.

For example, the i5-9600K's spec of 3.7GHz means "all i5-9600K chips are 100% stable at 3.7GHz." But some chips can run at 4.8GHz, while others become unstable at 4.2GHz.

I got lucky. My chip ran stably at 4.6GHz with 1.25V. But my friend bought the same i5-9600K, and his needed 1.32V to hit 4.6GHz.

Same product, but why the difference? Microscopic differences in silicon crystal structure, position on the wafer (edge vs. center), tiny variables in the manufacturing process—all these factors matter.

This is the Silicon Lottery. You pay the same price, but some people get great chips, and some get mediocre ones.

Overclocking is eating into this "Safety Margin". If you're lucky (Silicon Lottery winner), you hit the jackpot. If not, it crashes.

Overclocking success doesn't end at booting. You need to verify "Is it actually stable?" It's not enough to just boot up—it needs to run for hours under full load without errors.

Prime95 is a program that stress-tests the CPU by putting it under 100% load. It calculates prime numbers while maxing out all cores.

I ran it for 8 hours. Left it running overnight and checked in the morning.

Prime95 Test Results:

- 4.6GHz, 1.25V

- Test Duration: 8 hours

- Errors: 0

- Max Temperature: 78°C

- Average Temperature: 72°C

If no errors occur, you can consider it a "stable overclock."

Prime95 tests stability, while Cinebench measures actual performance. It runs 3D rendering tasks and scores the results.

Cinebench R20 Results:

- Stock (3.7GHz): 2,450 points

- Overclocked (4.6GHz): 3,050 points

- Performance Gain: ~24%

A 24% performance gain is significant. But I realized this wasn't free.

Beyond programs like Prime95, I created my own stress test script.

import multiprocessing

import time

import psutil

def stress_test_worker():

"""Function to max out one CPU core"""

end_time = time.time() + 60 # Run for 60 seconds

while time.time() < end_time:

# Repeat meaningless calculations to spike CPU usage

_ = sum([i**2 for i in range(10000)])

def run_stress_test():

"""Load all CPU cores"""

cpu_count = multiprocessing.cpu_count()

print(f"CPU Core Count: {cpu_count}")

print("Starting stress test...")

# Assign processes to all cores

processes = []

for _ in range(cpu_count):

p = multiprocessing.Process(target=stress_test_worker)

p.start()

processes.append(p)

# Monitor CPU temperature and usage

for i in range(60):

cpu_percent = psutil.cpu_percent(interval=1)

temps = psutil.sensors_temperatures()

if 'coretemp' in temps:

core_temps = [t.current for t in temps['coretemp']]

avg_temp = sum(core_temps) / len(core_temps)

print(f"[{i+1}s] CPU Usage: {cpu_percent}% | Avg Temp: {avg_temp:.1f}°C")

# Terminate processes

for p in processes:

p.join()

print("Stress test complete")

if __name__ == "__main__":

run_stress_test()

Running this script maxes out all CPU cores at 100% and shows temperatures climbing. After overclocking, running this shows whether throttling occurs and how high temperatures get.

After understanding overclocking, this analogy clicked:

"Removing the factory-imposed 150km/h limit on a race car that can actually hit 200km/h on the highway."The car (CPU) can go 200km/h. The engine is strong, the structure is solid. But the manufacturer (Intel) imposes a 150km/h limit to "prevent potential accidents."

But the driver (user) decides, "I have a good highway (cooling system) and I drive well (monitoring), so I can safely go 200km/h," and removes the limit.

Of course, there are risks:

But if done correctly, you get "free" (sort of) performance.

As a server developer, I realized there's no such thing as overclocking in cloud environments (AWS). In servers where stability is everything, trading a 1% crash risk for 24% performance is insanity.

But for personal PCs—especially gaming or video editing rigs—it's still an attractive option.

Through this experience, I came to understand a few things:

Through this experience, I internalized that "Performance, Power, Heat, and Stability" are always locked in a trade-off relationship.

Raise one, and another falls:

In the end, this is what I learned: "There's no such thing as free. But if you do it right, it can be worth it."