SSD vs HDD: How Storage Devices Work

LP records vs USB drives. Why physically spinning disks are inherently slow, and how SSDs made servers 100x faster.

LP records vs USB drives. Why physically spinning disks are inherently slow, and how SSDs made servers 100x faster.

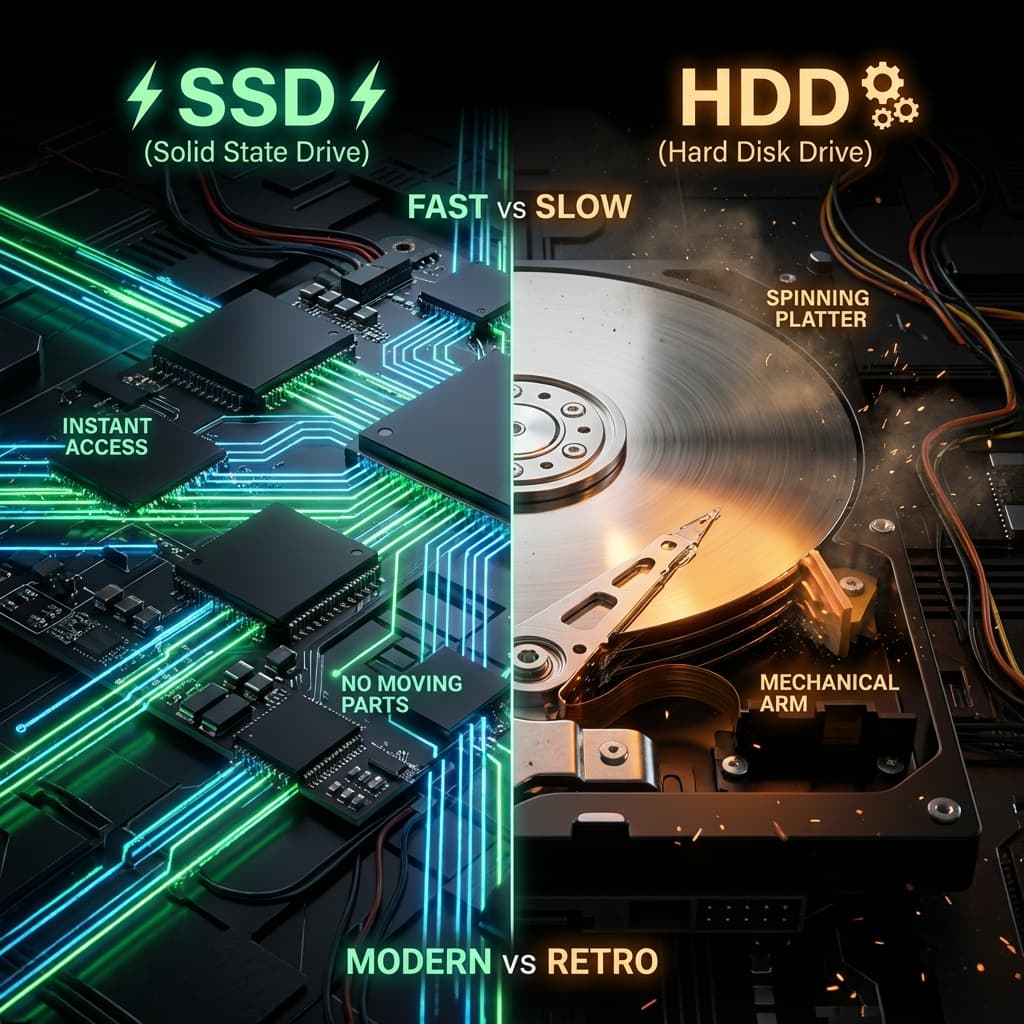

Why does MacBook battery last long? Should I use AWS Graviton? A deep dive into the philosophy of CISC (Complex) vs RISC (Simple) architectures.

The gold mine of AI era, NVIDIA GPUs. Why do we run AI on gaming graphics cards? Learn the difference between workers (CUDA) and matrix geniuses (Tensor Cores).

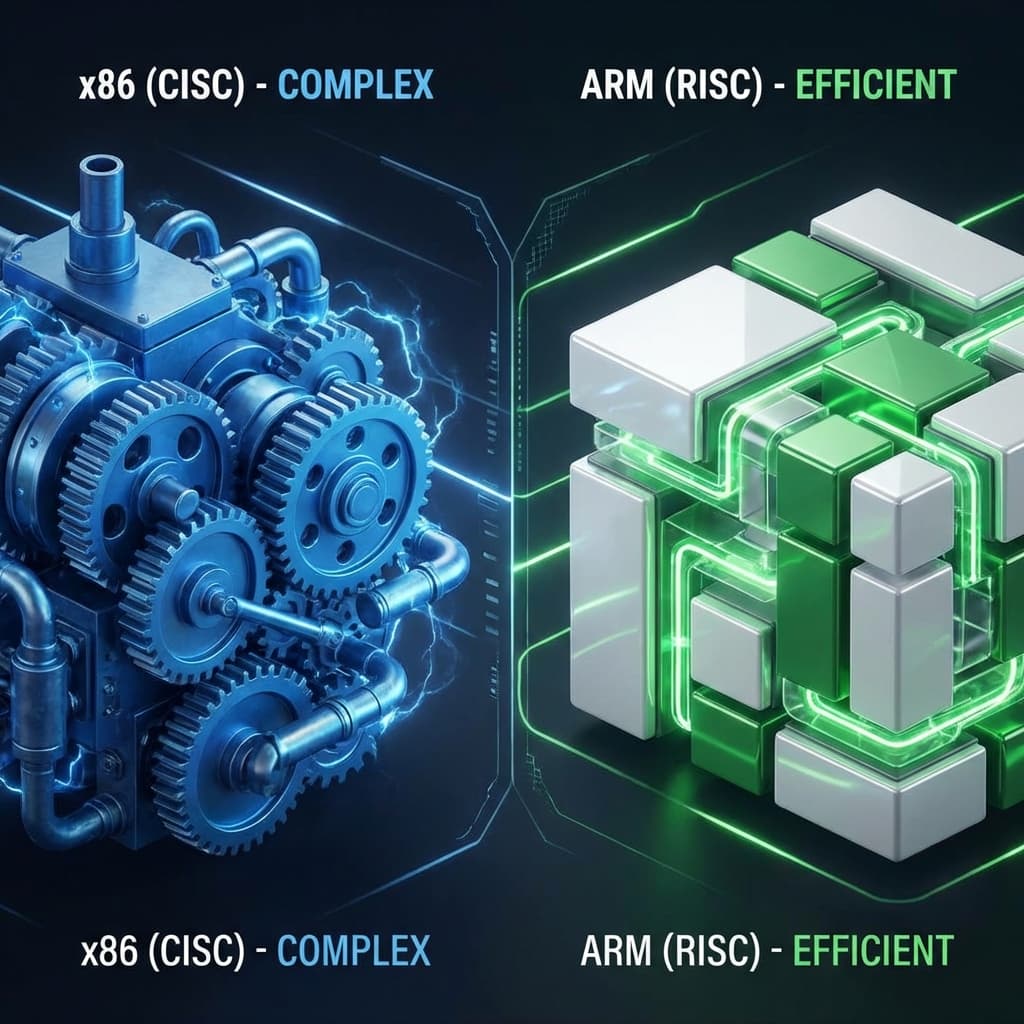

Bought a fast SSD but it's still slow? One-lane country road (SATA) vs 16-lane highway (NVMe).

I thought the motherboard was just a board to plug things into. Then I learned what a chipset does.

Back when I was a junior, my service slowed down. My senior asked, "What storage is the DB running on?" "Probably... just a hard drive?" He looked at me with pity and told me to switch to an SSD. Like magic, all problems vanished. I had spent all night tuning SQL queries, but it was just hardware lag.

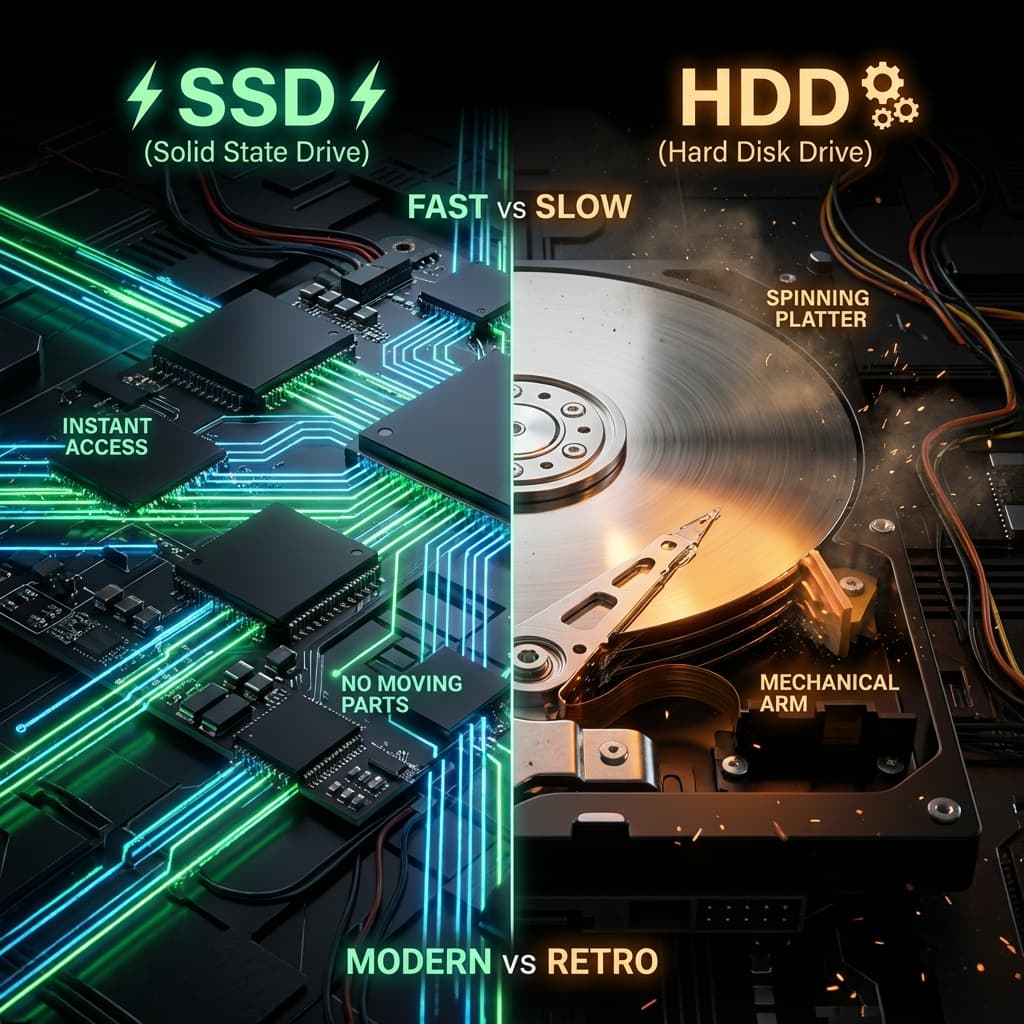

What is the difference between SSD and HDD that creates such a gap? It's the difference between a Vinyl Record and a USB Thumb Drive.

At first I thought HDD was just "a slower SSD." Same kind of storage, different speed. I was wrong. The mechanism itself was completely different.

HDD is a Vinyl Record (LP).

Because of this "Physical Movement," there is a definite speed limit.

I thought of a librarian analogy. An HDD is a librarian walking to fetch books from shelves. The farther the book, the slower. If 10 books are scattered across different shelves? The librarian has to walk back and forth 10 times.

That's why using an HDD for a DB server is a disaster. Databases often "read 1,000 tiny pieces of data one at a time." The HDD needle goes crazy trying to find all 1,000 locations.

SSD is a USB Thumb Drive.

I imagined a teleporting librarian. The moment the librarian knows where a book is, they teleport there and grab it. 10 scattered books? No problem. Just teleport 10 times.

This is when it clicked. "SSD is fast at random access, HDD is fast at sequential access."

SSD is not magic. It traps electrons in semiconductor chips, but this "electron prison" isn't eternal.

NAND Flash, the core of SSDs, comes in types. It depends on how many bits you store per cell.

| Type | Bits/Cell | Lifespan (P/E Cycles) | Speed | Price | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC (Single-Level Cell) | 1 | 100,000 | Fastest | Very expensive | Enterprise servers, industrial |

| MLC (Multi-Level Cell) | 2 | 10,000 | Fast | Expensive | High-end laptops, workstations |

| TLC (Triple-Level Cell) | 3 | 3,000 | Moderate | Affordable | Consumer SSDs (most of us) |

| QLC (Quad-Level Cell) | 4 | 1,000 | Slow | Cheap | High-capacity storage (read-heavy) |

P/E Cycles means Program/Erase Cycles. Simply put, "how many times can you write and erase?"

When I first saw these numbers, I panicked. "TLC can only handle 3,000 writes? Won't it break soon?"

Turns out Wear Leveling makes it fine.

SSD controllers are smart. They don't keep writing to the same cells. They use all cells evenly.

For example, say you write and delete a 10GB file daily on a 256GB SSD. The controller writes this file to a different physical location each time. It rotates through the entire 256GB.

Result: A TLC SSD (3,000 P/E Cycles, 256GB) can theoretically write 256GB × 3,000 = 768TB. If you write 10GB per day? You can use it for 210 years.

Now I get it. SSDs last way longer than I thought.

But SSDs have one more trap. If you write 1GB, you actually write 1.5GB.

Why? SSDs can't overwrite in place.

A block contains multiple pages.

To modify a 4KB file?

You modified 4KB but wrote 256KB. This is Write Amplification.

This problem is mitigated by the TRIM command.

When you delete a file, the OS doesn't actually erase the data. It just marks the space as "free" in the file table.

Problem: The SSD doesn't know this. It still thinks valid data exists there. When you try to write new data to that space? You go through the "read → modify → erase → write" process.

TRIM command tells the SSD: "These blocks are no longer used. You can erase them in advance."

The SSD erases these blocks during idle time. Writing new data later becomes much faster.

Checking if TRIM is enabled on Linux:

# Check if TRIM schedule is active

systemctl status fstrim.timer

# Manually run TRIM (when SSD performance drops)

sudo fstrim -v /

I once had an SSD slow down after a few months because I didn't know this. One TRIM run brought it back to full speed.

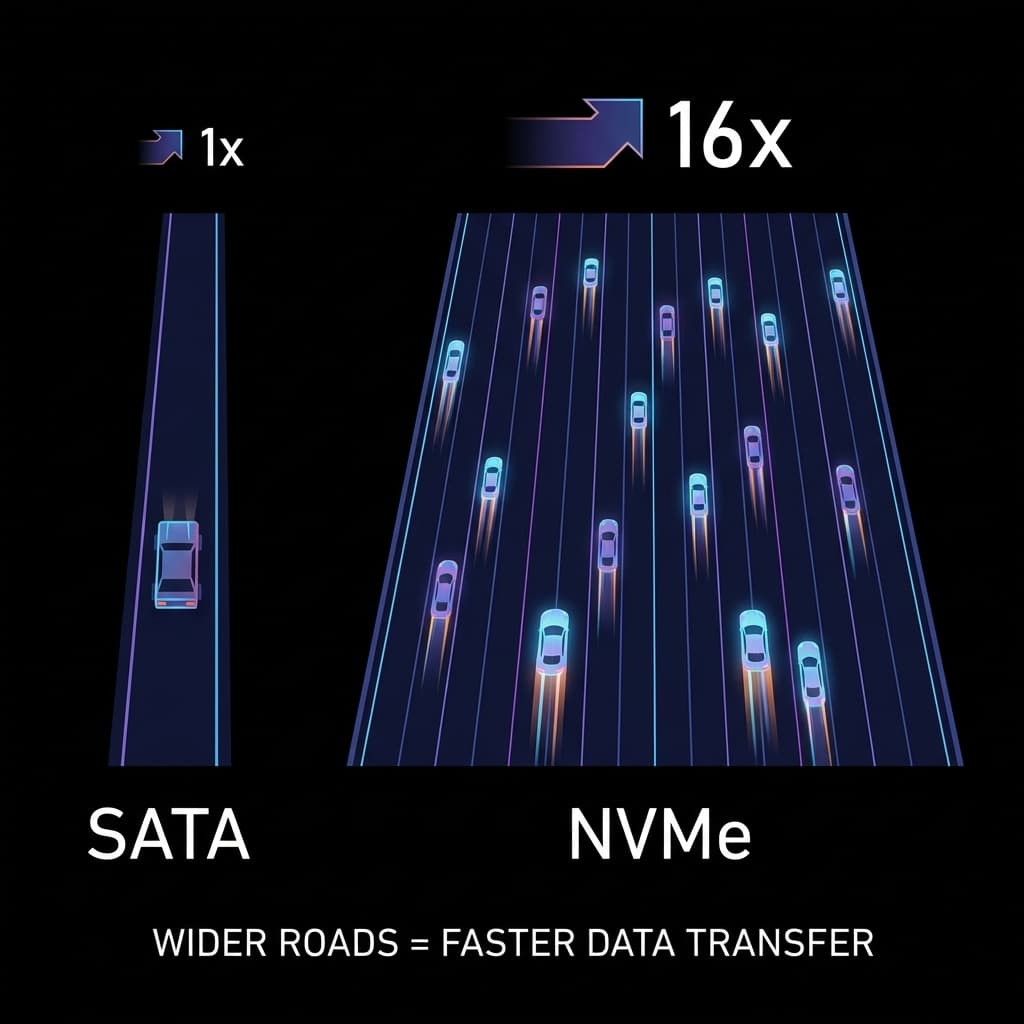

One of the most critical metrics in server performance is IOPS (Input/Output Operations Per Second). Simply put: "How many times can you read/write per second?"

Do you see it? 100 vs 50,000. Running a DB (which reads/writes tiny data constantly) on an HDD is like putting a Ferrari engine (CPU) on a car with millstones for wheels (HDD).

When you run a server on AWS, you have to choose an EBS (Elastic Block Store) volume. At first I didn't know what this was, so I just used the default (gp2).

Later I realized IOPS affects pricing dramatically.

| Type | IOPS | Throughput | Use Case | Price (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gp3 (General Purpose SSD) | 3,000 ~ 16,000 (configurable) | 125 ~ 1,000 MB/s | Most workloads | Cheap (default) |

| gp2 (Old General Purpose SSD) | 100 ~ 16,000 (scales with size) | 250 MB/s | Old default | More expensive than gp3 |

| io1 (Provisioned IOPS) | Up to 64,000 | 1,000 MB/s | DB servers, high performance | Very expensive |

| io2 (Next-gen io1) | Up to 64,000 | 1,000 MB/s | Mission-critical DB | Even more expensive (99.999% durability) |

| st1 (HDD) | 500 | 500 MB/s | Logs, big data | Cheap |

| sc1 (Cold HDD) | 250 | 250 MB/s | Archives, backups | Cheapest |

Key insight:

In my experience, gp3 was enough for most cases. Unless your DB server handles tens of thousands of queries per second.

If RDS performance is slow, first check IOPS usage in CloudWatch.

# Monitor disk I/O on EC2 instance

iostat -x 1

# Check which process is using disk the most

sudo iotop

I didn't know these commands at first. When my server slowed down, I only checked CPU and memory, then discovered disk I/O was the bottleneck way too late.

"Is my server SSD actually fast?" I sometimes wonder. Especially with cloud servers, since they're invisible.

You can benchmark directly with fio (Flexible I/O Tester).

# Install fio (Ubuntu)

sudo apt install fio

# Random read IOPS test (4KB blocks)

fio --name=random-read \

--ioengine=libaio \

--iodepth=64 \

--rw=randread \

--bs=4k \

--direct=1 \

--size=1G \

--numjobs=4 \

--runtime=60 \

--group_reporting

# Random write IOPS test (4KB blocks)

fio --name=random-write \

--ioengine=libaio \

--iodepth=64 \

--rw=randwrite \

--bs=4k \

--direct=1 \

--size=1G \

--numjobs=4 \

--runtime=60 \

--group_reporting

Interpreting results:

read: IOPS=12345 in the output.I ran this test once and realized: "Oh, my local MacBook SSD is genuinely fast. AWS gp3 is slower than I thought."

Cloud uses shared storage, so if a neighboring server uses disk heavily, my performance drops too. That's why provisioned IOPS (io1/io2) is expensive. It guarantees dedicated performance.

So is SSD always the answer? The problem is Cost. HDD is overwhelmingly cheaper per gigabyte.

So you have to separate storage based on "how often you use the data."

How I applied this in practice:

1. RDS DB ServerThis cut storage costs by 60%.

| Type | HDD | SSD |

|---|---|---|

| Analogy | Vinyl Record (LP) | Smartphone Memory |

| Mechanism | Physical Rotation (Motor) | Semiconductor (Chips) |

| IOPS | 100 ~ 200 | 50,000+ |

| Use Case | Backups, Video Archives | OS, DB, Web Server |

Remembering just this will prevent half of your server outages.

And one more thing. "Separate storage based on how often you use the data."

HDD is slow but cheap. Perfect for Cold Data. SSD is fast but expensive. Use it only for Hot Data to avoid cost explosion.

From my trial-and-error experience, following these two rules eliminates most storage problems.