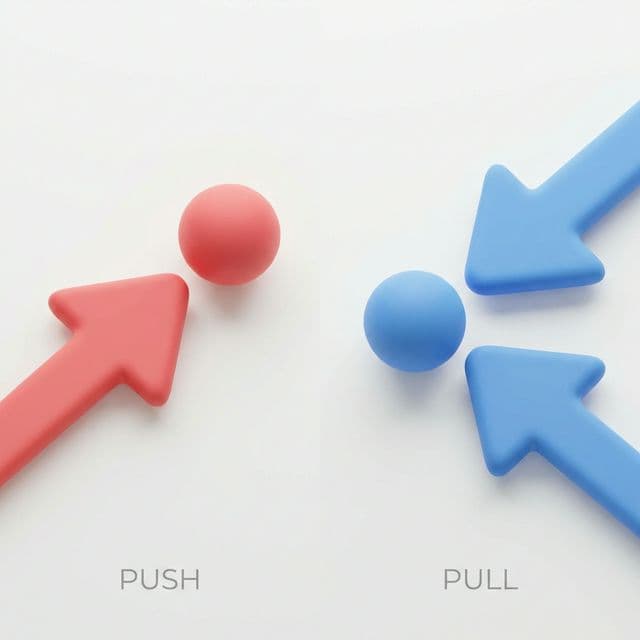

News Feed System Design: Push vs Pull and the Fan-out Problem

Building a feed like Instagram sounds simple until a user with 1M followers posts. Understanding push vs pull models and fan-out strategies.

Building a feed like Instagram sounds simple until a user with 1M followers posts. Understanding push vs pull models and fan-out strategies.

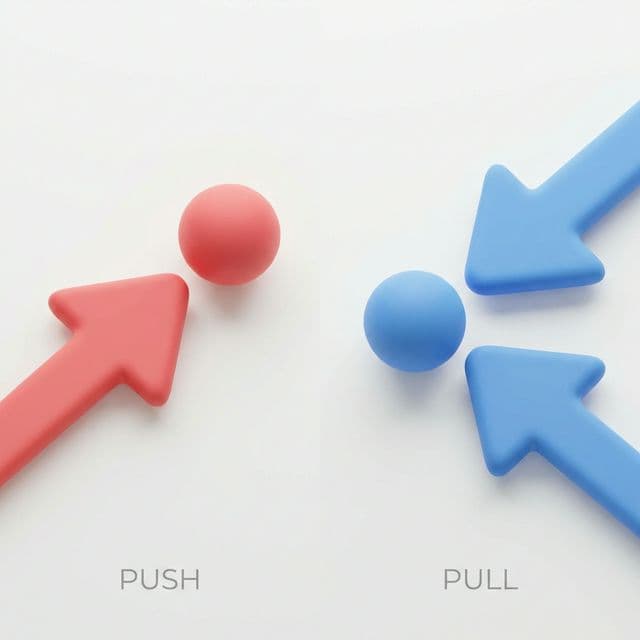

Why is the CPU fast but the computer slow? I explore the revolutionary idea of the 80-year-old Von Neumann architecture and the fatal bottleneck it left behind.

ChatGPT answers questions. AI Agents plan, use tools, and complete tasks autonomously. Understanding this difference changes how you build with AI.

Integrating a payment API is just the beginning. Idempotency, refund flows, and double-charge prevention make payment systems genuinely hard.

When you don't want to go yourself, the proxy goes for you. Hide your identity with Forward Proxy, protect your server with Reverse Proxy. Same middleman, different loyalties.

When I started building a social media project, the feed was the first thing I needed to tackle. "Just show recent posts from people I follow," I thought. Simple enough, right? But when I actually sat down to implement it, things got complicated fast.

My initial approach was naive. Every time a user opens their feed, fetch all posts from everyone they follow and sort by time. Done. And honestly, it worked fine when following 10 or 100 people.

But then scale hit me. What if a celebrity with 1 million followers posts? What if a user follows 1,000 people? Suddenly, database queries crawled to a halt and servers started groaning under the load.

That's when it clicked. A feed isn't just a simple read operation—it's a system design problem about choosing the right trade-off between reads and writes.

My initial implementation was the Pull model. Fetch data in real-time whenever a user requests their feed.

-- Typical Pull model query

SELECT posts.*

FROM posts

WHERE user_id IN (

SELECT followed_id

FROM follows

WHERE follower_id = 'current_user_id'

)

ORDER BY created_at DESC

LIMIT 20;

Think of it like going to a library. You walk in with a list of your favorite authors, then manually search for their latest books on the shelves. Every single visit, you repeat the entire search process.

But as my user base grew, the cracks started showing.

// Feed loading time for user following 1000 people

const startTime = Date.now();

const feed = await getFeedPull(userId);

const loadTime = Date.now() - startTime;

console.log(`Load time: ${loadTime}ms`); // 3000ms... way too slow!

I realized Pull alone couldn't scale to Instagram or Twitter levels.

That's when I discovered the Push model. A completely different approach: pre-compute and insert posts into every follower's feed the moment they're created.

It's like newspaper delivery. When the press prints a new paper, they deliver it to every subscriber's mailbox in advance. Subscribers just open their mailbox—instant access.

// Push model: fan-out on write

async function createPost(userId: string, content: string) {

// 1. Create the post

const post = await db.posts.create({

user_id: userId,

content: content,

created_at: new Date()

});

// 2. Fan-out to all followers

const followers = await db.follows.findMany({

where: { followed_id: userId }

});

// 3. Insert into each follower's feed table

const feedInserts = followers.map(follower => ({

user_id: follower.follower_id,

post_id: post.id,

created_at: post.created_at

}));

await db.feeds.createMany({ data: feedInserts });

return post;

}

// Reading the feed is blazing fast

async function getFeedPush(userId: string) {

return await db.feeds.findMany({

where: { user_id: userId },

include: { post: true },

orderBy: { created_at: 'desc' },

take: 20

});

}

But implementing Push exposed me to the fan-out problem. This was a real headache.

// What if a celebrity with 1M followers posts?

const celebrity = { id: 'celeb_123', followers: 1_000_000 };

await createPost(celebrity.id, 'Hello everyone!');

// Need to insert 1 MILLION database records...

// This could take minutes!

Fan-out is when a single post "explodes" into thousands or millions of feed entries. The more followers someone has, the more expensive each post becomes to write.

Storage is another concern. If 1 million followers each store 20 posts in their feed, that's 20 million records—most of which will never even be read.

The real insight came here: "Why did I think I had to choose just one?"

Studying how Twitter actually works taught me this. They use different strategies for different user types.

// Hybrid model: strategy based on user type

async function createPostHybrid(userId: string, content: string) {

const post = await db.posts.create({

user_id: userId,

content: content,

created_at: new Date()

});

const user = await db.users.findUnique({ where: { id: userId } });

// Strategy depends on follower count

if (user.followers_count > 100_000) {

// Celebrity: no push, handle with pull

console.log('Celebrity post - will be pulled on demand');

return post;

}

// Regular user: push (fan-out)

const followers = await db.follows.findMany({

where: { followed_id: userId }

});

const feedInserts = followers.map(follower => ({

user_id: follower.follower_id,

post_id: post.id,

created_at: post.created_at

}));

await db.feeds.createMany({ data: feedInserts });

return post;

}

// Hybrid feed retrieval

async function getFeedHybrid(userId: string) {

// 1. Get pushed feed (posts from regular users)

const pushedFeed = await db.feeds.findMany({

where: { user_id: userId },

include: { post: { include: { user: true } } },

orderBy: { created_at: 'desc' },

take: 50

});

// 2. Pull celebrity posts in real-time

const celebritiesFollowed = await db.follows.findMany({

where: {

follower_id: userId,

followed: { followers_count: { gte: 100_000 } }

}

});

const celebrityPosts = await db.posts.findMany({

where: {

user_id: { in: celebritiesFollowed.map(f => f.followed_id) },

created_at: { gte: new Date(Date.now() - 7 * 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000) }

},

include: { user: true },

orderBy: { created_at: 'desc' }

});

// 3. Merge and sort

const merged = [...pushedFeed, ...celebrityPosts]

.sort((a, b) => b.created_at.getTime() - a.created_at.getTime())

.slice(0, 20);

return merged;

}

The key insight is the Pareto Principle. Most users have few followers. Only 1% of celebrities have hundreds of thousands. So handle 99% efficiently with Push, and just 1% with Pull.

It's like a restaurant kitchen. Popular dishes are pre-prepped (Push), while special orders are made-to-order (Pull). You can't prep everything in advance, and you can't make everything to order.

// Feed table design

interface FeedItem {

id: string;

user_id: string; // Owner of this feed

post_id: string; // Post reference

author_id: string; // Post author

created_at: Date; // Post creation time

inserted_at: Date; // When inserted into feed

}

// Indexes are crucial

// CREATE INDEX idx_feeds_user_created ON feeds(user_id, created_at DESC);

Why store both inserted_at and created_at? Because you might need to regenerate feeds or adjust ordering later.

Chronological order alone isn't enough. Like Instagram or Facebook, you need to consider engagement.

// Simple ranking score

function calculateFeedScore(post: Post, user: User): number {

const ageInHours = (Date.now() - post.created_at.getTime()) / (1000 * 60 * 60);

// Recency: exponential decay over time

const recencyScore = Math.exp(-ageInHours / 24);

// Popularity: likes, comments, shares

const popularityScore =

post.likes_count * 1.0 +

post.comments_count * 2.0 +

post.shares_count * 3.0;

// Affinity: past interactions with author

const affinityScore = calculateAffinity(user, post.author);

// Weighted sum

return (

recencyScore * 0.5 +

Math.log(1 + popularityScore) * 0.3 +

affinityScore * 0.2

);

}

// Sort feed by score

async function getRankedFeed(userId: string) {

const rawFeed = await getFeedHybrid(userId);

const user = await db.users.findUnique({ where: { id: userId } });

return rawFeed

.map(item => ({

...item,

score: calculateFeedScore(item.post, user)

}))

.sort((a, b) => b.score - a.score)

.slice(0, 20);

}

I initially used offset-based pagination and ran into problems.

// Offset approach (bad)

async function getFeedOffset(userId: string, page: number) {

return await db.feeds.findMany({

where: { user_id: userId },

orderBy: { created_at: 'desc' },

skip: page * 20,

take: 20

});

}

// Problem: if new posts arrive while user is viewing page 2,

// page 3 will have duplicates or missing items!

The solution was cursor-based pagination.

// Cursor approach (good)

async function getFeedCursor(userId: string, cursor?: string) {

const where: any = { user_id: userId };

if (cursor) {

// Only fetch items after the cursor (last item's created_at)

where.created_at = { lt: new Date(cursor) };

}

const items = await db.feeds.findMany({

where,

orderBy: { created_at: 'desc' },

take: 21 // Fetch one extra to check if more pages exist

});

const hasMore = items.length > 20;

const feed = items.slice(0, 20);

const nextCursor = hasMore ? feed[feed.length - 1].created_at.toISOString() : null;

return { feed, nextCursor, hasMore };

}

Feeds are perfect for caching, especially in the Push model.

// Redis-based feed caching

import Redis from 'ioredis';

const redis = new Redis();

async function getCachedFeed(userId: string): Promise<FeedItem[]> {

const cacheKey = `feed:${userId}`;

// 1. Check cache

const cached = await redis.get(cacheKey);

if (cached) {

return JSON.parse(cached);

}

// 2. Fetch from DB

const feed = await getFeedHybrid(userId);

// 3. Store in cache (5 min TTL)

await redis.setex(cacheKey, 300, JSON.stringify(feed));

return feed;

}

// Invalidate cache when new post is pushed

async function invalidateFeedCache(userId: string) {

await redis.del(`feed:${userId}`);

}

// Better approach: Redis Sorted Set

async function pushToFeedCache(userId: string, postId: string, timestamp: number) {

const cacheKey = `feed:${userId}`;

// Add to sorted set (timestamp as score)

await redis.zadd(cacheKey, timestamp, postId);

// Keep only latest 1000 items

await redis.zremrangebyrank(cacheKey, 0, -1001);

// Set TTL

await redis.expire(cacheKey, 3600);

}

async function getFeedFromCache(userId: string, limit: number = 20) {

const cacheKey = `feed:${userId}`;

// Get in reverse chronological order

const postIds = await redis.zrevrange(cacheKey, 0, limit - 1);

if (postIds.length === 0) {

return null; // Cache miss

}

// Batch fetch post data

const posts = await db.posts.findMany({

where: { id: { in: postIds } },

include: { user: true }

});

// Maintain original order

const postMap = new Map(posts.map(p => [p.id, p]));

return postIds.map(id => postMap.get(id)).filter(Boolean);

}

Using Redis Sorted Sets lets you manage feeds memory-efficiently. Store only post IDs, and batch-fetch actual data when needed.

Twitter switched from pure Pull to Hybrid in 2012. Their engineering blog taught me a lot.

Interestingly, Twitter built a separate "Timeline Service" microservice. The feed generation logic became so complex they had to isolate it.

Instagram is a bit different. With photo-heavy content, media loading optimization is more critical.

What's interesting about Instagram is they manage "Stories" as a completely separate system. The 24-hour expiration requires different strategies.

The key lessons from building feed systems:

No perfect solution: Neither Pull nor Push is optimal for all cases. Hybrid is the pragmatic choice.

Design for scale: Start simple, but if you plan to grow, think about your migration path early.

Measurement matters: Monitor feed load times, write latency, cache hit rates to find bottlenecks.

Caching is essential: Memory is cheap. Aggressive Redis usage solves many problems.

Use cursor-based pagination: Offset-based pagination breaks with real-time feeds.

Make fan-out async: Post creation can't be slow. Handle fan-out in background jobs.

Ultimately, feed systems are about finding the balance between reads and writes. Understand user behavior patterns, decide where to store data, and when to compute it.

The realistic path is: start with Pull for simplicity, gradually introduce Push as traffic grows, and evolve to Hybrid as you scale further.

Now when I build a feed in my next project, I'll design it with confidence.