Von Neumann Architecture: The Design Principles of Modern Computers

Why is the CPU fast but the computer slow? I explore the revolutionary idea of the 80-year-old Von Neumann architecture and the fatal bottleneck it left behind.

Why is the CPU fast but the computer slow? I explore the revolutionary idea of the 80-year-old Von Neumann architecture and the fatal bottleneck it left behind.

Why does my server crash? OS's desperate struggle to manage limited memory. War against Fragmentation.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

Fast by name. Partitioning around a Pivot. Why is it the standard library choice despite O(N²) worst case?

Establishing TCP connection is expensive. Reuse it for multiple requests.

I bought a brand new MacBook Air with the M3 chip a few months ago. I was hyped. "Finally, no more heat issues, right? This thing should fly."

Wrong.

Within a week, I had my usual setup running: thirty Chrome tabs open, a few Docker containers spinning, VS Code indexing files. And there it was again — that familiar warmth radiating from the bottom of the laptop.

"Wait a second. Isn't this supposed to be cutting-edge? Why is it still heating up?"

At first, I blamed myself. "I must be pushing it too hard." But then I dug into computer architecture, and I discovered something mind-blowing.

The CPU wasn't overheating because it was working too hard. It was overheating because it was waiting.Waiting for what? Data. Data stuck in traffic on a narrow road between the memory and the processor.

Every computer you've ever touched — your phone, your gaming rig, even a supercomputer — is built on a blueprint designed in 1945 called the Von Neumann Architecture. And that blueprint, brilliant as it was, came with a fatal flaw baked into its very foundation.

Today, I want to walk you through what the genius mathematician John von Neumann gave us, and what he left behind: a performance problem we're still wrestling with eighty years later.

Let me paint you a picture of how computers worked before Von Neumann's breakthrough.

Imagine you're working with ENIAC, one of the earliest electronic computers. You want it to add 1 + 1. Simple, right?

Not quite.

You'd have to physically rewire the machine. Engineers would crawl around this massive room-sized computer, plugging and unplugging cables to connect the right circuits for addition. Then, if you wanted to switch from addition to subtraction? Start over. Unplug everything. Rewire the whole thing for the subtraction circuit. This could take hours, sometimes days.

It's like if every time you wanted to switch from Safari to Spotify, you had to disassemble your iPhone and resolder the circuit board.

Programs weren't software. They were hardware configurations. The instructions were literally hard-wired into the machine.

Von Neumann saw this inefficiency and had a radical idea:

"What if we stop rewiring the machine every time, and instead store the instructions as numbers in memory?"

Here's what made Von Neumann's idea revolutionary:

This was the birth of the Stored-Program Computer.

Suddenly, you didn't need to rewire anything. Want to run a different program? Just overwrite the file in memory. Done.

This is the moment software became independent from hardware. It's why you can download an app from the internet instead of buying a custom-built machine for every task.

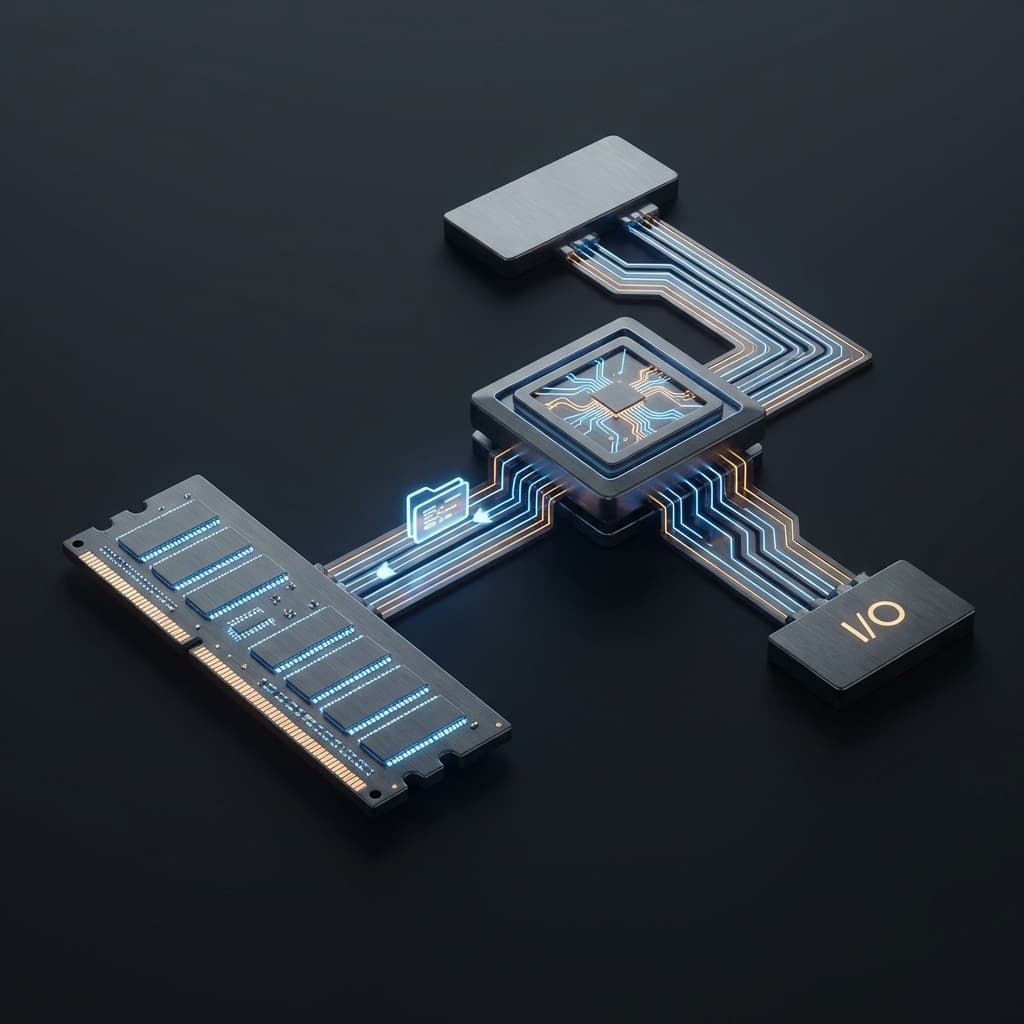

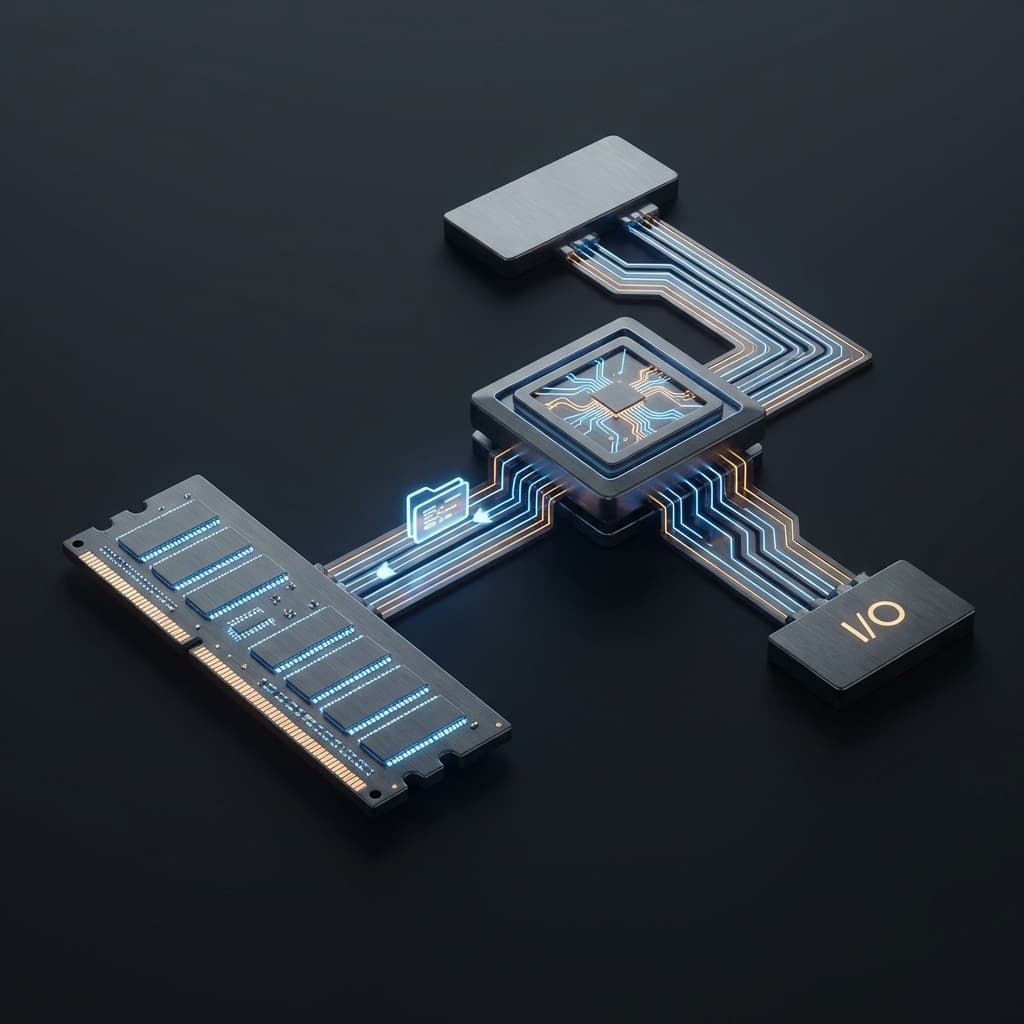

Von Neumann's design breaks down into three core components. If you've ever built a PC or looked at a computer spec sheet, you've seen these:

graph TD

subgraph CPU

CU[Control Unit]

ALU[Arithmetic Logic Unit]

Reg[Registers]

end

Memory[Memory\n(Program + Data)]

Bus[System Bus]

CPU <==> Bus

Bus <==> Memory

It looks elegant. Modular. Easy to upgrade. You can swap out parts, rewrite software, and the whole system just works.

But there's a catch.

A big one.

Here's the problem with modern technology: it doesn't evolve evenly.

Over the last few decades, CPUs have gotten thousands of times faster. Intel's 8086 from 1978 ran at 5 MHz. Today's chips run at 5 GHz — a thousand times faster. And that's not even counting multi-core parallelism or instruction-level optimizations.

But memory (DRAM) hasn't kept up. It's gotten bigger, sure, but not proportionally faster.

So here's the analogy that made it click for me:

Your CPU can execute 5 billion operations per second (5 GHz). But if the bus can only deliver 100 million pieces of data per second, what happens?

The CPU idles.It doesn't just sit there peacefully. It burns power while waiting. This is where heat comes from. This is where performance tanks.

This is the Von Neumann Bottleneck.

Instructions and data share the same bus. They're stuck in the same traffic jam. No matter how fast your CPU is, it's only as fast as the data it can fetch.

When I learned about the Von Neumann Bottleneck, I had a flashback to every backend performance issue I've ever debugged.

Your web server (the CPU) processes logic blazingly fast. But where does it always slow down?

Fetching data from the database.The network connection between your server and your database is the bus. The database is the memory. And if you're making too many trips, you're stuck in traffic.

Here's a classic example:

// The infamous N+1 problem

const users = await db.query('SELECT * FROM users'); // 1 trip to the DB

for (const user of users) {

// N more trips — one for EACH user

const orders = await db.query('SELECT * FROM orders WHERE user_id = ?', [user.id]);

process(orders);

}

This code isn't slow because JavaScript is slow. It's slow because you're taking the bus too many times.

The principle is identical whether you're talking about hardware (CPU and RAM) or software (server and database). The bottleneck isn't in the processing — it's in the fetching.

CPUs aren't sitting idle while we complain about bottlenecks. They've developed clever tricks to overlap work and reduce waiting time. One of the most important optimizations is instruction pipelining.

Here's how a CPU executes an instruction:

The old way was to do these steps one at a time, sequentially. Finish instruction A completely, then start instruction B.

But that's wasteful. While you're decoding instruction A, the fetch unit is just sitting there doing nothing.

Modern CPUs use a pipeline — like an assembly line in a factory. Each stage handles a different instruction simultaneously:

Time 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

────────────────────────────────────────

Inst A F D E W

Inst B F D E W

Inst C F D E W

Inst D F D E W

In theory, this means the CPU can finish one instruction per clock cycle, even though each instruction takes multiple cycles to complete.

But there's a catch: data dependencies.

ADD R1, R2, R3 ; R1 = R2 + R3

SUB R4, R1, R5 ; R4 = R1 - R5 (Uh oh, R1 isn't ready yet!)

If instruction B needs the result of instruction A, the pipeline stalls. The CPU has to wait. And we're right back to the bottleneck.

This is why raw clock speed doesn't tell the whole story. A 5 GHz CPU that stalls constantly can be slower than a 3 GHz CPU with better pipelining and cache efficiency.

Over the decades, computer scientists have thrown everything at this problem. Here are the big ones:

The idea: "If going all the way to RAM is too slow, why not stash frequently used data right next to the CPU?"

That's what cache memory is. Modern CPUs have three levels:

When the CPU needs data, it checks L1 first. If it's there (a cache hit), great — ultra-fast access. If not (a cache miss), it checks L2, then L3, and finally goes to main memory.

This is exactly why we use Redis or Memcached in web apps. Same principle. Keep hot data close to the processor (your server), avoid expensive trips to the database (main memory).

The bottleneck exists because instructions and data share the same bus.

Harvard Architecture solves this by physically splitting them. You get:

This allows the CPU to fetch the next instruction while processing data from the current one. No more waiting in line.

Pure Harvard Architecture is rare in general-purpose computers (it's expensive and inflexible), but modern CPUs use a Modified Harvard Architecture internally. L1 cache is split into instruction cache (I-cache) and data cache (D-cache), giving you the benefits of Harvard at the cache level while keeping the external memory system simple.

In a pure Von Neumann system, the CPU is the middleman for everything. Want to read a file from disk into memory? The CPU has to copy it, byte by byte.

That's insane.

DMA lets devices (like your hard drive or network card) write directly to memory without bothering the CPU.

Before DMA:

Disk → CPU registers → RAM (CPU does all the lifting)

With DMA:

Disk → (DMA controller) → RAM (CPU is free to do other work)

This is why file transfers don't peg your CPU at 100%. DMA handles the heavy lifting in the background.

Traditional PCs have separate memory for the CPU (RAM) and GPU (VRAM). When you're editing a video, the CPU processes some data, then copies it to the GPU's memory. The GPU renders, then copies the result back.

All that copying? Bottleneck city.

Apple's M1, M2, and M3 chips use Unified Memory Architecture. The CPU and GPU share the same physical memory pool. No copying. No waiting.

I tested this myself. I ran the same 4K video encoding task on:

The difference isn't just clock speed. It's zero-copy architecture. The GPU doesn't wait for data to be transferred. It's already there.

This is why Apple Silicon crushes it in video editing, machine learning, and graphics work. The bottleneck has been architected away.

Understanding the Von Neumann Bottleneck changed how I write code.

I used to think performance was about clever algorithms and tight loops. And sure, those matter. But most performance problems aren't in the computation — they're in the data movement.

Here's what I keep in mind now:

Whether it's hitting a database, calling an API, or reading from disk — batch your requests.

Bad:

for (const id of userIds) {

const user = await fetchUser(id); // 100 users = 100 requests

}

Good:

const users = await fetchUsersBatch(userIds); // 1 request

If you're fetching the same data repeatedly, cache it.

In hardware, that's L1/L2/L3 cache. In software, that's Redis, CDN, or even in-memory variables.

Modern CPUs are fast when you access memory sequentially. When you jump around randomly (pointer chasing, hash table lookups), cache efficiency tanks.

Arrays are faster than linked lists not because of Big-O notation, but because of cache locality.

When your code is waiting for I/O (disk, network, database), it's idling — just like a CPU waiting on the bus.

Async programming lets you overlap waiting time with useful work, just like instruction pipelining in a CPU.

When I first heard the term "Von Neumann Architecture," I thought it was just some old historical trivia. Dead guy's name attached to a textbook diagram.

But the more I learned, the more I realized: this is the blueprint for everything. Every phone, laptop, server, and supercomputer follows this design.

And the bottleneck Von Neumann introduced in 1945? We're still fighting it.

Cache hierarchies. Pipelining. DMA. Unified memory. Harvard modifications. These aren't just cool features — they're workarounds for a fundamental design limitation.

All code boils down to three steps:

And the slowest step, almost always, is step 1.

Your code isn't slow because your algorithm is bad. It's slow because it's waiting for data.

So the next time your app feels sluggish, ask yourself: where is my CPU (or server) stuck waiting? What's my bottleneck? And how can I reduce the trips to the warehouse?

Because at the end of the day, we're all just trying to outsmart an 80-year-old traffic problem.

Here are the key terms I wish someone had explained to me when I first started learning about computer architecture.

The revolutionary idea that programs (instructions) and data can both be stored in the same memory, as opposed to hard-wiring instructions into hardware. This is the foundation of software as we know it.

The communication pathway connecting the CPU, memory, and peripherals. Data, addresses, and control signals all travel through the bus. In Von Neumann systems, instructions and data share the same bus, causing contention.

The performance limitation caused by the shared bus architecture. No matter how fast the CPU is, it can only process data as fast as it can fetch it from memory.

A technique where the CPU overlaps the execution of multiple instructions by breaking them into stages (fetch, decode, execute, write-back) and processing different instructions at different stages simultaneously.

Small, ultra-fast memory located on or near the CPU. It stores frequently accessed data to reduce trips to slower main memory. Organized into levels (L1, L2, L3).

A computer architecture with separate memory and buses for instructions and data, allowing simultaneous access to both. Reduces the Von Neumann Bottleneck but adds cost and complexity.

A feature that allows hardware devices (like disk controllers or network cards) to transfer data directly to/from memory without involving the CPU, freeing the CPU to do other work.

A design (used in Apple Silicon) where the CPU and GPU share the same physical memory, eliminating the need to copy data between separate memory pools and reducing latency.

These are frequently asked questions, or things I was genuinely confused about when learning this material.

Von Neumann: Instructions and data share the same memory and bus. Simpler, more flexible, but suffers from the bottleneck.

Harvard: Separate memory and buses for instructions and data. Faster, but more expensive and complex. Common in embedded systems (like microcontrollers).

Real-world hybrid: Most modern CPUs use a Modified Harvard Architecture — external memory is Von Neumann, but internal cache is split (I-cache and D-cache).

Because of the Von Neumann Bottleneck. If your CPU goes from 3 GHz to 6 GHz, but memory speed stays the same, the CPU just spends more time waiting. This is why, after the mid-2000s, CPU clock speeds plateaued. Instead of faster clocks, we got more cores, bigger caches, and better parallelism.

Cache only helps if the data you need is already there (a cache hit). If the CPU needs data that's not in cache (a cache miss), it has to go all the way to main memory.

Workloads with poor cache locality (random access patterns, pointer chasing, large datasets) still suffer from bottlenecks. This is why arrays are faster than linked lists in practice, even if they have the same Big-O complexity.

Before it, changing a program meant physically rewiring the computer. It could take days. With stored programs, you just load different code into memory. This is the foundation of general-purpose computing and why you can run millions of different apps on the same hardware.

On traditional systems:

CPU Memory → (copy over PCIe bus) → GPU Memory

This copy step is expensive and slow. With Unified Memory:

CPU and GPU both access the same memory (no copy needed)

For tasks that require heavy CPU-GPU collaboration (video editing, 3D rendering, machine learning), this is a massive win. It's not magic — it's eliminating a bottleneck by design.

Absolutely. Especially when:

The hardware bottleneck and the software bottleneck are the same problem: moving data is expensive. Minimize it.