GPU VRAM: The Graphics Card's Dedicated Memory

Ever hit 'CUDA Out of Memory' while training a deep learning model? Understanding the difference between VRAM and regular RAM.

Ever hit 'CUDA Out of Memory' while training a deep learning model? Understanding the difference between VRAM and regular RAM.

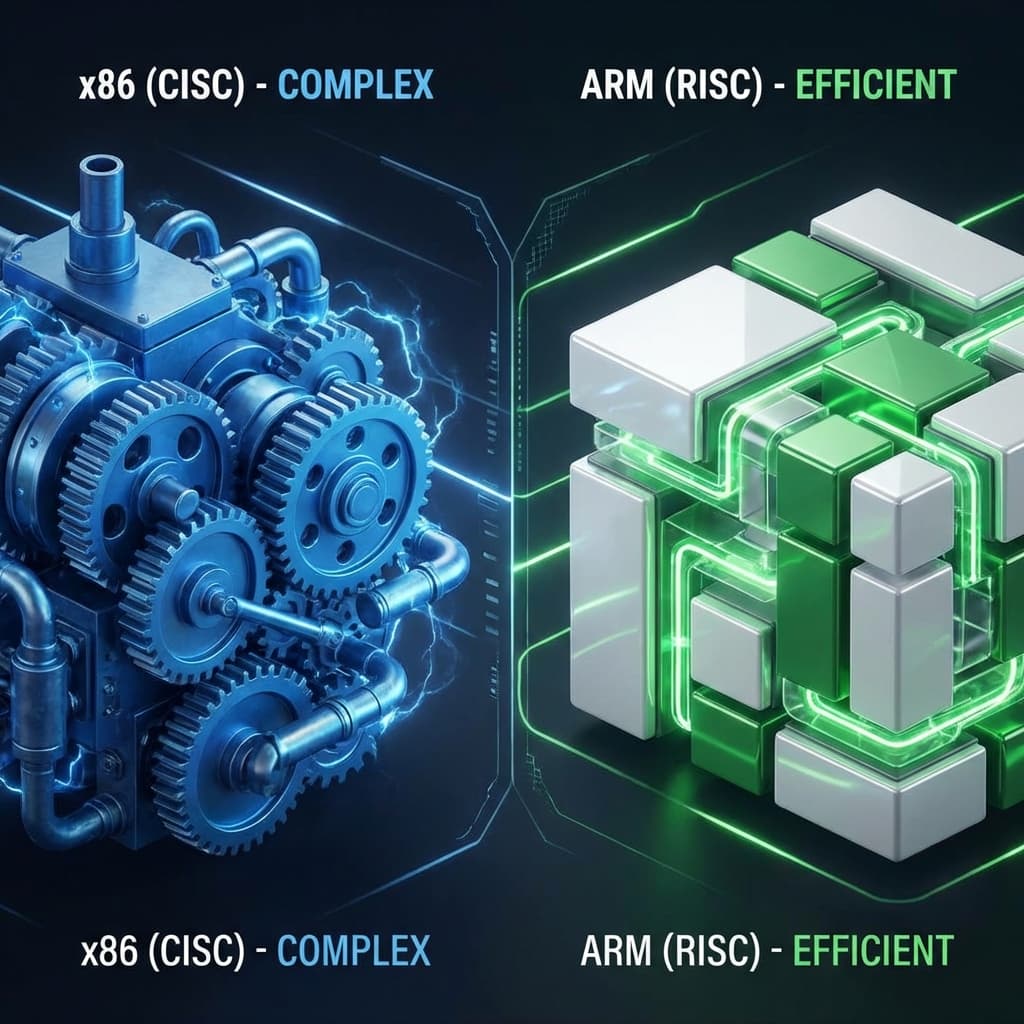

Why does MacBook battery last long? Should I use AWS Graviton? A deep dive into the philosophy of CISC (Complex) vs RISC (Simple) architectures.

The gold mine of AI era, NVIDIA GPUs. Why do we run AI on gaming graphics cards? Learn the difference between workers (CUDA) and matrix geniuses (Tensor Cores).

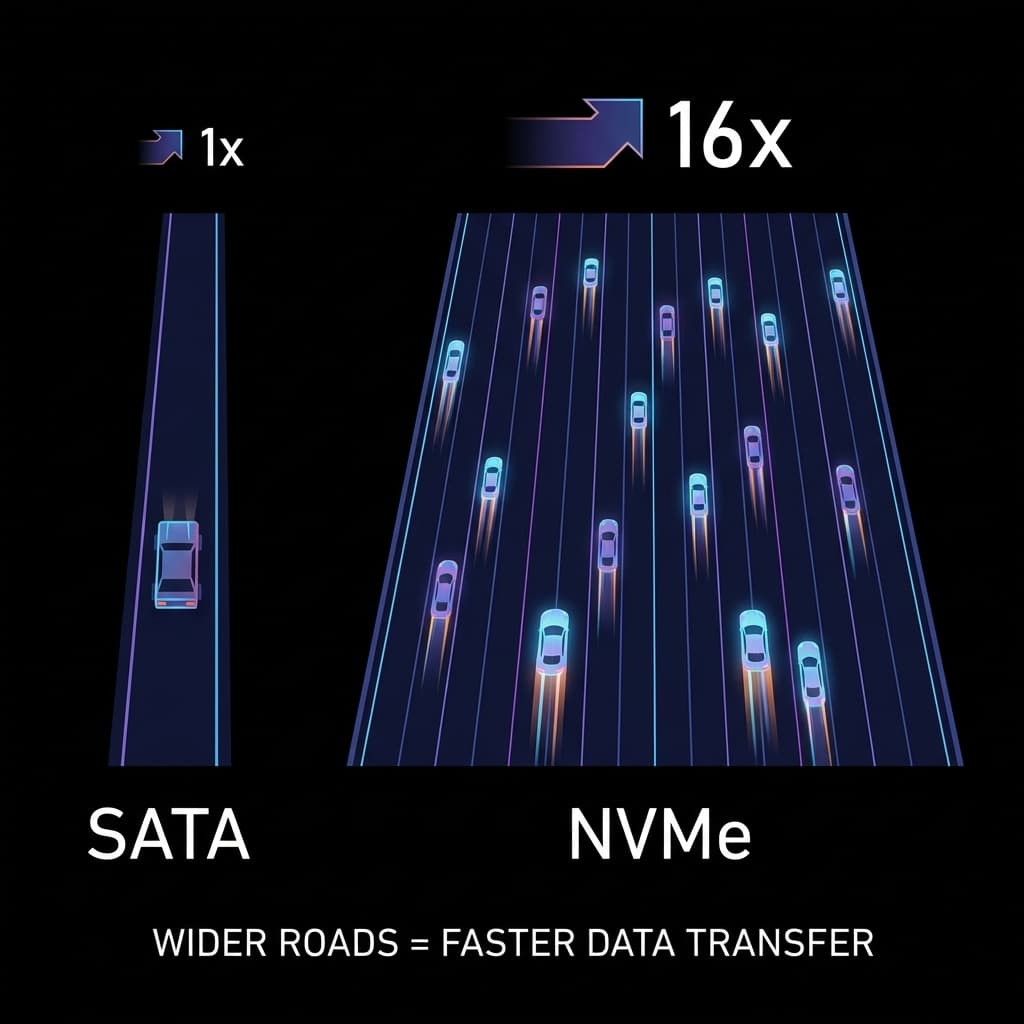

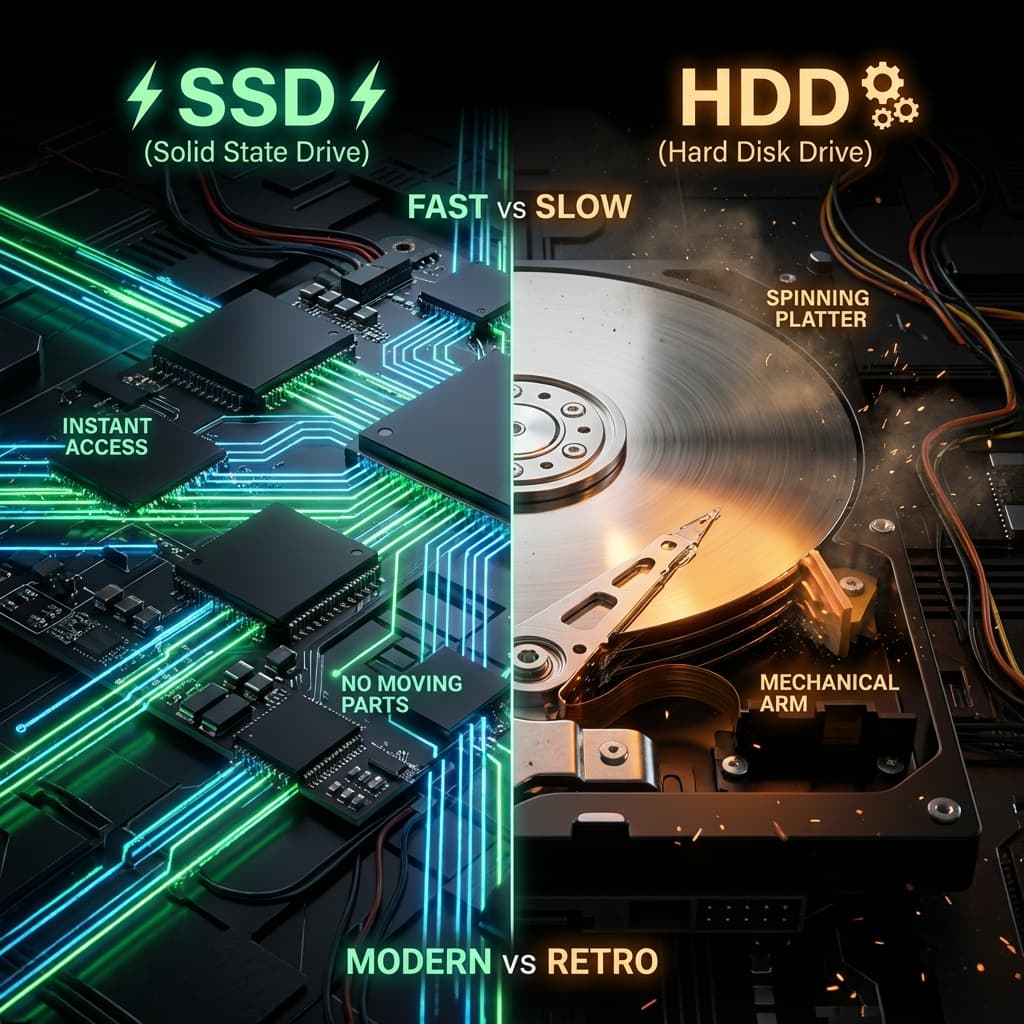

Bought a fast SSD but it's still slow? One-lane country road (SATA) vs 16-lane highway (NVMe).

LP records vs USB drives. Why physically spinning disks are inherently slow, and how SSDs made servers 100x faster.

I was excitingly coding to run an AI model (Stable Diffusion) on my local machine.

As soon as I hit run, I got this error:

RuntimeError: CUDA out of memory.

My PC has 32GB of RAM. Why is it saying memory is insufficient? That's when I learned for the first time: GPU only eats from its own bowl (VRAM).

At first, I was confused. "What's so special about GPU that it needs separate memory?" But as I dug deeper, I understood this wasn't just GPU being stubborn. It was a physically inevitable design choice.

To understand this, the "Kitchen Analogy" works best again.

It didn't matter that my RAM was huge (32GB). The GPU Chef is stubborn: "I only cook what's on MY cutting board (VRAM)." My graphics card was an RTX 3060 with 12GB VRAM. Even if RAM is full of ingredients, if they don't fit on the 12GB cutting board, the Chef refuses to cook.

Initially, I thought it was "inflexible design." But once I understood why, I realized "If they didn't design it this way, GPU wouldn't work at all."

I complained, "Can't they just share? Why so rigid?" But I understood once I saw the 'Speed (Bandwidth)' difference.

If fetching data from RAM is like a water tap, Fetching data from VRAM is like a Firehose blasting water.

The GPU needs to crunch billions of calculations per second. It can't wait for data to trickle in from slow RAM. That's why they soldered this "Insanely fast and expensive dedicated memory (GDDR)" right next to the chip.

Bandwidth clicked for me with the highway analogy.

GPU wins by "how much data it can process at once." A narrow road simply can't compete, so "building a wide highway right next to the chip" is what VRAM is all about.

I thought all VRAM was the same. But comparing graphics cards, I kept seeing terms like "GDDR6" and "HBM2". What's the difference?

Most gaming GPUs (RTX 3060, 4090, etc.) use this.

When RTX 3060 says "12GB GDDR6," it means "12GB capacity of GDDR6 memory." I used to only look at capacity numbers, but now I understand "what type of memory" matters too.

Used in datacenter GPUs (A100, H100) or some AMD cards.

HBM is overkill for gaming, but essential for "data-intensive tasks like AI training." Why Nvidia A100 costs tens of thousands of dollars? HBM is the answer.

This explained "why server GPUs cost way more than gaming GPUs." It's not just about core count. The memory itself is a different league.

"Compromise your graphic settings" in games basically means managing VRAM. 4K Textures are massive. If they don't fit on the VRAM cutting board, the GPU stops cooking or forcibly lowers quality.

Same with AI. Large Language Models (LLM) or Image models are gigabytes in size. You must Load them onto VRAM to run Inference.

When I first ran Stable Diffusion, the model file itself was around 4GB. But running it consumed over 8GB of VRAM. "Wait, the file is 4GB, why does it use 8GB?"

Turns out when you load a model onto VRAM, intermediate computation results (Activations) also occupy space. In cooking terms, it's not just the ingredients (model file), but also the chopped ingredients (intermediate results) on the cutting board.

So thinking "4GB model = 4GB VRAM needed" is naive. Actually, you need 2~3x the model size in VRAM. I learned this the hard way.

Now I understand why "Model Quantization" (dieting the model) is so popular. It's a desperate effort to shrink the ingredients so they fit on the expensive, limited VRAM cutting board.

Deep learning model numbers (weights) are stored as FP32 (32-bit floating point) by default. Each number takes 32 bits (4 bytes).

For example, a model with 1 billion parameters:

This difference determines "whether I can run it on my GPU or not." RTX 3060 (12GB VRAM) can't handle FP32 models, but compressed to INT8, it's doable.

The "photo resolution reduction" analogy clicked for me.

Same with AI models. FP16 or INT8 often have almost no practical accuracy loss. That's why most deployed models now offer FP16 or INT8 versions.

This freed me from thinking "Out of VRAM = buy expensive GPU." Now I know "compress the model" is a viable option.

After hitting CUDA Out of Memory errors multiple times, I realized "knowing how much VRAM I'm using" is crucial.

On Linux or Windows, open a terminal and type nvidia-smi to see current GPU status.

nvidia-smi

Sample output:

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| NVIDIA-SMI 525.105.17 Driver Version: 525.105.17 CUDA Version: 12.0 |

|-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

| GPU Name Persistence-M| Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap| Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

|===============================+======================+======================|

| 0 NVIDIA GeForce ... Off | 00000000:01:00.0 On | N/A |

| 30% 45C P8 15W / 170W | 8234MiB / 12288MiB | 2% Default |

+-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

The key part is Memory-Usage.

8234MiB / 12288MiB means "using 8GB out of 12GB."

Seeing this, I could judge: "Oh, I have 4GB headroom. I can increase batch size a bit."

You can also check VRAM usage inside your code.

import torch

# Check currently allocated VRAM (in bytes)

allocated = torch.cuda.memory_allocated()

print(f"Allocated memory: {allocated / 1024**3:.2f} GB")

# Total VRAM reserved by CUDA

reserved = torch.cuda.memory_reserved()

print(f"Reserved memory: {reserved / 1024**3:.2f} GB")

# Clear VRAM cache

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

Initially, I thought "just reduce batch size when error happens." But monitoring memory usage in real-time made training much more efficient.

Especially torch.cuda.empty_cache() "cleans up unused memory," and calling it periodically drastically reduced Out of Memory errors.

Studying GPU VRAM, I found a completely different approach: Apple M series and AMD APU.

Standard PCs have separate RAM for CPU and VRAM for GPU. Every time CPU sends data to GPU, it must "Copy" it.

But Apple M1/M2 share a single memory pool between CPU and GPU.

At first, I thought "Why is this better? It's slower, right?" But "no copy time" turned out to be a bigger win than expected.

Especially in video editing or 3D rendering, CPU and GPU frequently exchange data, where unified memory shines.

Traditional architecture is a "bucket brigade."

Unified memory is "one big barrel."

This analogy made me understand "why Apple M series emphasizes memory capacity." Since it's unified, choosing 16GB means CPU and GPU share it. If GPU uses 12GB, CPU only gets 4GB.

That's why when buying M series Macs, "don't just think VRAM, get plenty of total memory." Lesson learned.

After countless CUDA Out of Memory errors, I compiled some workarounds.

Most immediate fix.

# Original

train_loader = DataLoader(dataset, batch_size=32)

# Low VRAM

train_loader = DataLoader(dataset, batch_size=16) # Half

Reducing batch size lowers data processed at once, significantly cutting VRAM usage. But training slows down a bit.

Small batch size can make training unstable. Use "accumulate gradients multiple times before updating."

accumulation_steps = 4

for i, (images, labels) in enumerate(train_loader):

loss = model(images, labels)

loss = loss / accumulation_steps

loss.backward()

if (i + 1) % accumulation_steps == 0:

optimizer.step()

optimizer.zero_grad()

Batch size is 8, but accumulating 4 times "effectively acts like batch size 32." Save VRAM while maintaining training stability. Clever trick.

Using FP16 instead of FP32 cuts VRAM in half.

from torch.cuda.amp import autocast, GradScaler

scaler = GradScaler()

for images, labels in train_loader:

with autocast(): # Auto-convert to FP16

loss = model(images, labels)

scaler.scale(loss).backward()

scaler.step(optimizer)

scaler.update()

PyTorch's autocast automatically converts to FP16.

Accuracy stays nearly the same, VRAM usage drops dramatically. Magic.

Sometimes you have no choice but to shrink the model itself.

This is a "last resort," but almost mandatory for deployment.

| Type | System RAM | GPU VRAM |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Motherboard Slot | Soldered on GPU PCB (Not replaceable) |

| Speed (Bandwidth) | Fast (Tens of GB/s) | Insanely Fast (Hundreds of GB/s ~ 1TB/s) |

| Type | DDR4/DDR5 | GDDR6 (Gaming) / HBM3 (Server) |

| Analogy | Public Table | Chef's Private Board |

VRAM capacity determines "How big of a task you can handle at once." That's why Deep Learning practitioners hunt for expensive Nvidia GPUs, especially the VRAM monsters like the 3090 or 4090.

It all comes down to a simple truth: "You need a big cutting board to handle a big fish."

And I escaped from the "must buy expensive GPU" mindset. Compress models with Quantization, train with Mixed Precision, leverage unified memory architectures—"there's plenty you can do with limited VRAM." I've accepted that.

VRAM isn't just a number. It's the core spec determining "what work I can do." Now when choosing GPUs, I don't just look at core count. I also check VRAM capacity and type (GDDR vs HBM).