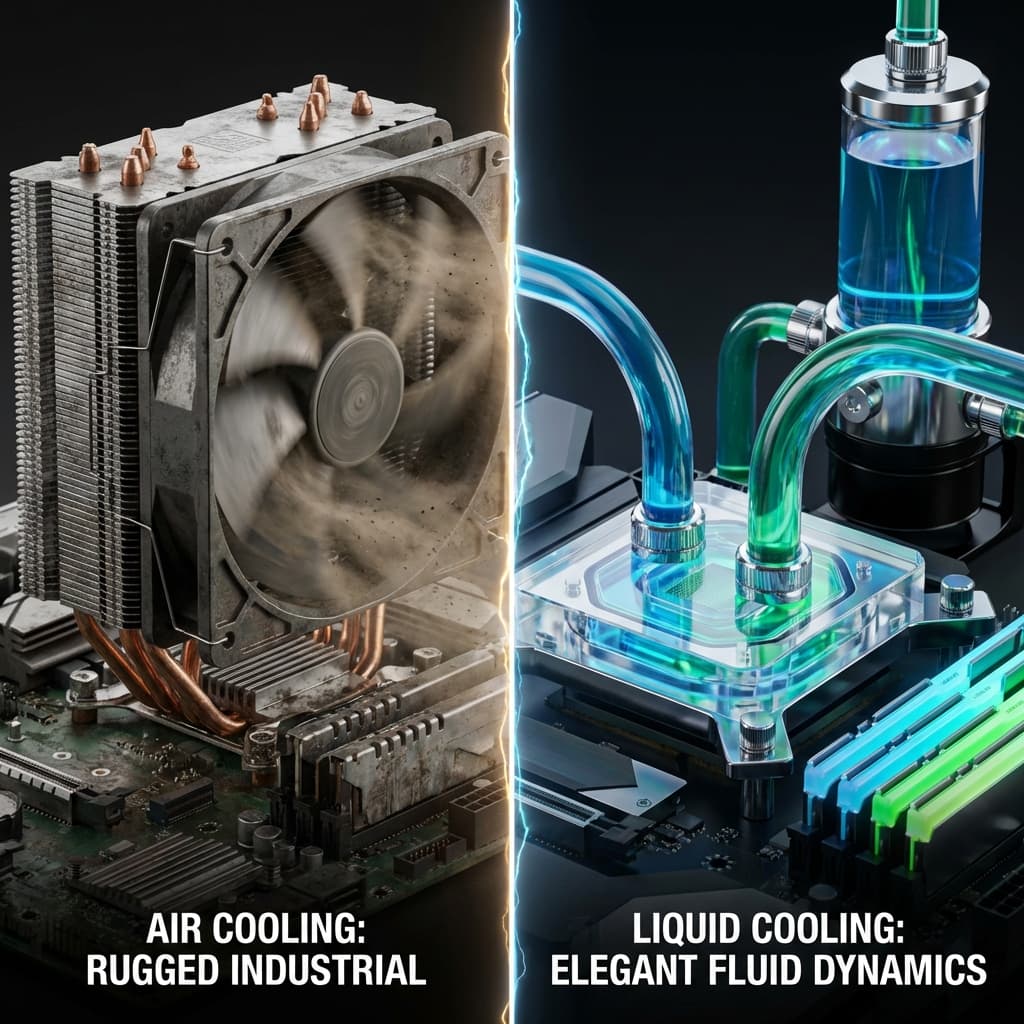

Cooling Systems: Air Cooling vs Liquid Cooling

Why does my PC sound like a jet engine every summer? Choosing between a fan breeze and a cold water shower for your CPU.

Why does my PC sound like a jet engine every summer? Choosing between a fan breeze and a cold water shower for your CPU.

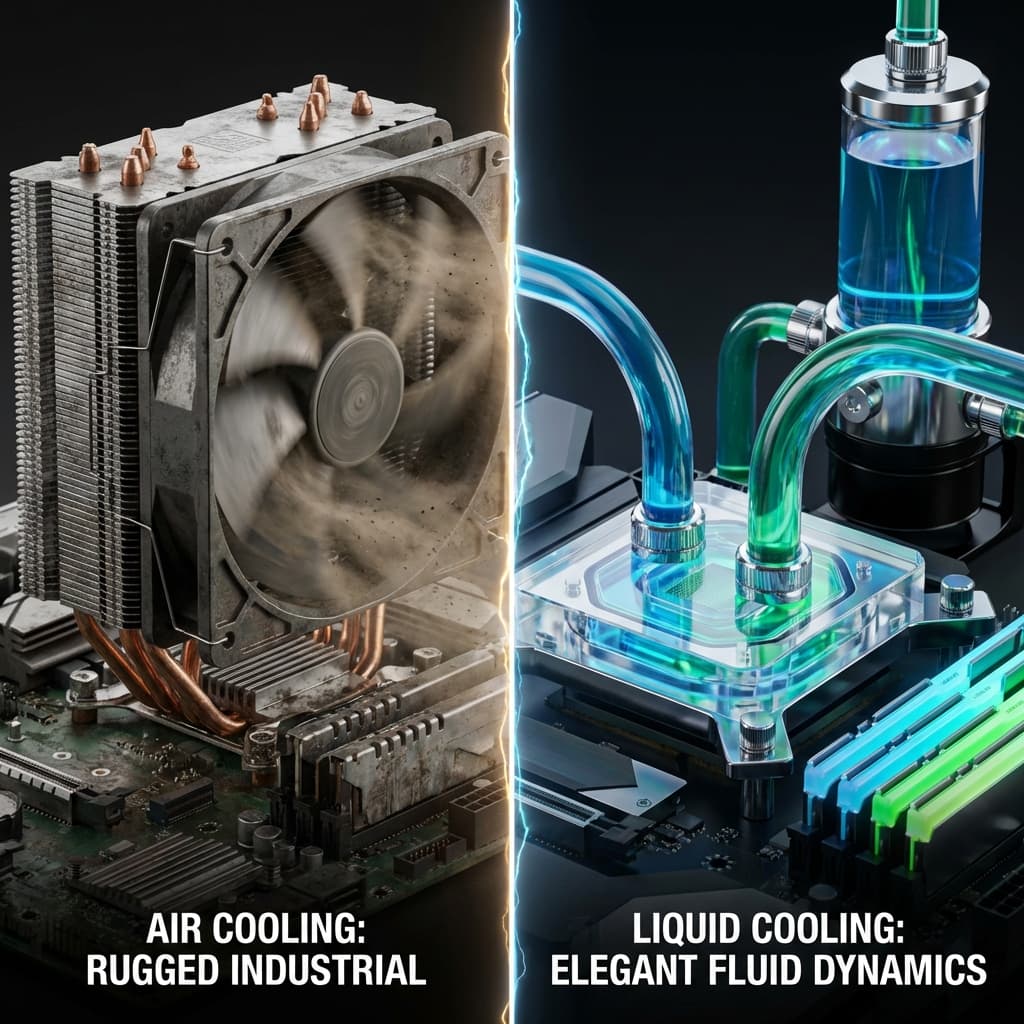

Why does MacBook battery last long? Should I use AWS Graviton? A deep dive into the philosophy of CISC (Complex) vs RISC (Simple) architectures.

The gold mine of AI era, NVIDIA GPUs. Why do we run AI on gaming graphics cards? Learn the difference between workers (CUDA) and matrix geniuses (Tensor Cores).

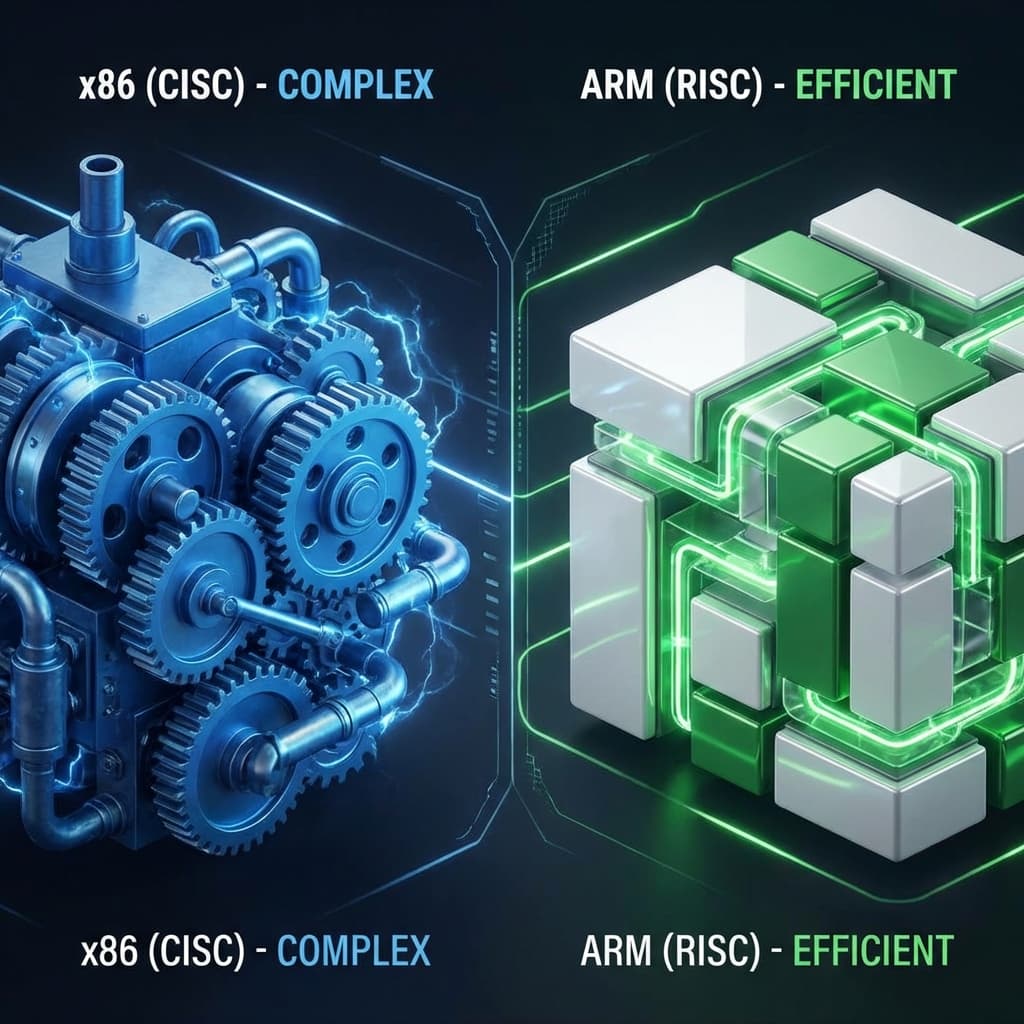

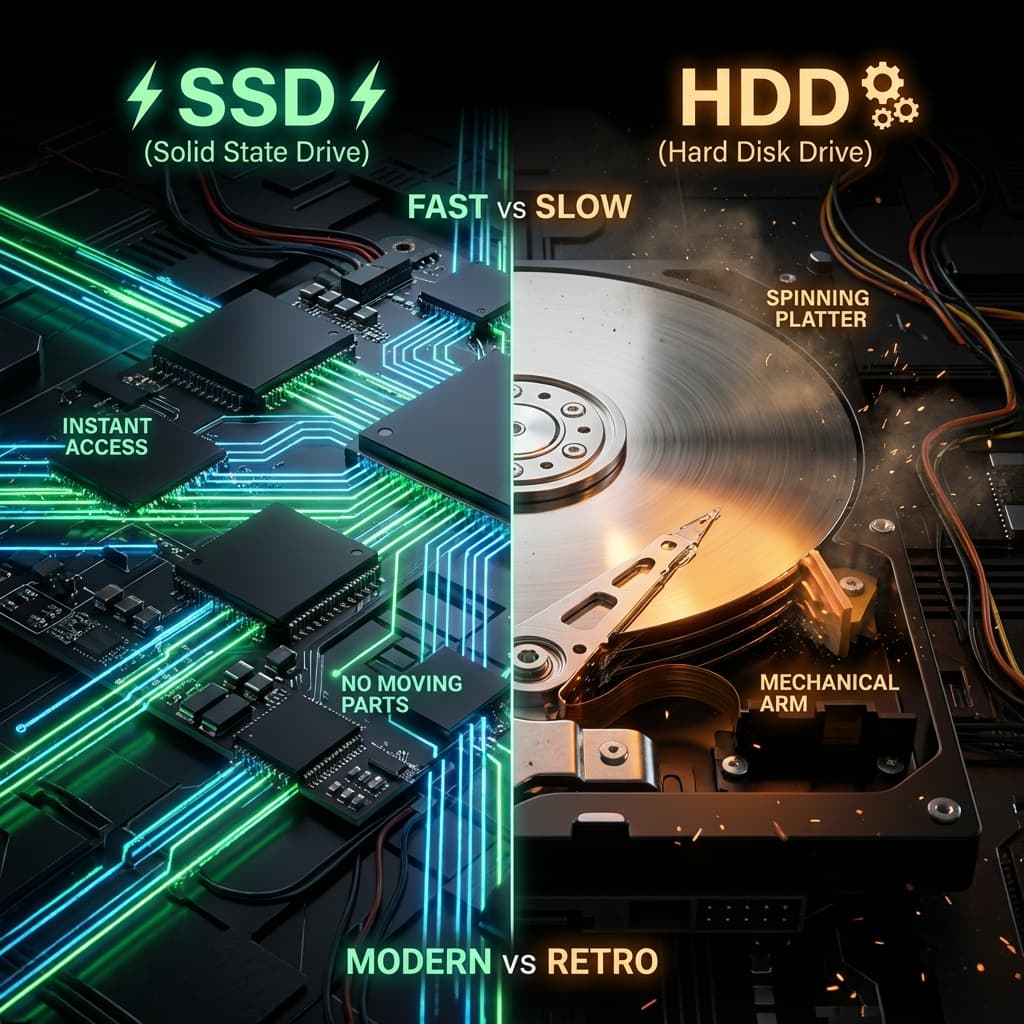

Bought a fast SSD but it's still slow? One-lane country road (SATA) vs 16-lane highway (NVMe).

LP records vs USB drives. Why physically spinning disks are inherently slow, and how SSDs made servers 100x faster.

One scorching summer afternoon, I was deep into a high-end gaming session when my PC started shutting down every 30 minutes. I opened the side panel and was hit by a wave of heat, like opening an oven door. I checked the CPU temperature: 95°C. That was the moment I truly understood the importance of cooling.

Computer components consume electricity and excrete heat as a byproduct. If you don't dispose of this waste heat quickly, components protect themselves by throttling performance or shutting down entirely. I learned this the hard way when compiling large projects on my development laptop. The build would slow to a crawl halfway through, not because of bad code, but because thermal throttling kicked in and my CPU clocked itself down to avoid melting.

This wasn't just a gaming problem. This was a fundamental constraint of all computing.

To understand cooling, we need to revisit high school physics. Heat always flows from hot to cold. There are exactly three mechanisms for this transfer:

Conduction: Touch a hand warmer and you feel warmth, right? Heat travels directly through solid materials. This is how heat moves from the CPU die to the heatsink base. Metals like copper and aluminum have high thermal conductivity, which is why they're used in coolers.

Convection: When you blow on hot soup to cool it down, you're using convection. Fluids (air or water) circulate and carry heat away. This is how heat moves from heatsink fins to the surrounding air. Stronger airflow means faster heat removal.

Radiation: Feel warm standing near a fireplace? That's thermal radiation, heat traveling as infrared light without needing a medium. This plays a minor role in computer cooling but does occur from case surfaces to the environment.

Understanding these three principles made cooling systems click for me. The entire chain follows this pattern: CPU → thermal paste (conduction) → heat pipes (conduction) → heatsink fins (conduction + convection) → air/water (convection) → outside case (convection + radiation). Every cooling solution is just optimizing this chain.

"Can't I just slap the cooler onto the CPU?" Absolutely not. Under a microscope, metal surfaces look like the lunar surface, full of peaks and valleys. Trapped between these microscopic gaps is air, which is an excellent insulator (think of why down jackets keep you warm—it's the trapped air).

Thermal paste is a thermally conductive compound that fills these microscopic air gaps. Apply a pea-sized amount to the CPU, and the temperature drops by 20°C. Without it, your CPU would thermal-throttle or shut down within a minute.

I once applied way too much thermal paste on my first build. It oozed out the sides and got all over the motherboard. Spent an hour cleaning it off with isopropyl alcohol. The golden rule: pea-sized amount, center of the CPU, let the cooler's mounting pressure spread it naturally. Too little leaves gaps. Too much actually reduces thermal conductivity because the paste itself isn't as conductive as metal-to-metal contact.

Thermal paste comes in various formulations: silicone-based, metal-based (liquid metal), ceramic-based. Liquid metal has the highest thermal conductivity but corrodes aluminum, so it's only safe with copper heatsinks. Use it wrong and your cooler literally dissolves. Learning these details made me feel like I'd leveled up in the hardware enthusiast skill tree.

Air cooling is the most common method:

Heat pipes are borderline magical. They contain a small amount of liquid that evaporates when heated and condenses when cooled. Capillary action circulates the fluid, transferring heat incredibly efficiently without requiring any power. It's passive cooling at its finest.

Advantages:I ran air cooling for years on mid-range builds. It worked fine until I upgraded to a high-end CPU and started running intensive workloads. The fan noise during builds was unbearable, and temps consistently hit the 80-85°C range under load.

When air cooling couldn't keep up, I invested in an AIO (All-In-One) liquid cooler. The principle is identical to a car radiator or home heating system:

The difference was night and day. If air cooling is like fanning yourself, liquid cooling is like stepping into a cold shower. It was quieter and significantly more powerful. But I couldn't shake the nagging fear: "What if it leaks and fries everything?"

AIO coolers are sealed units designed to last 5-7 years. Eventually, the pump wears out or liquid slowly permeates through tubing. When that happens, you replace the whole unit.

The coolant is typically distilled water mixed with corrosion inhibitors and dye. AIOs are sealed, so you can't refill them. Custom loops require periodic maintenance—you drain and refill the coolant every 1-2 years. Skip this and you'll grow algae or corrosion inside the tubes. I've seen transparent tubing turn murky green. That's game over.

Advantages:In real-world scenarios, you need to verify your cooling is working. Here's how to monitor temperatures on a Linux system:

# Install lm-sensors (Ubuntu/Debian)

sudo apt-get install lm-sensors

# Detect sensors (first-time setup)

sudo sensors-detect

# Check temperatures

sensors

# Sample output:

# coretemp-isa-0000

# Adapter: ISA adapter

# Package id 0: +52.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

# Core 0: +49.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

# Core 1: +51.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

# Core 2: +50.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

# Core 3: +52.0°C (high = +80.0°C, crit = +100.0°C)

This command shows real-time temperatures. "Package id 0" is the overall CPU temperature. Each core shows individually. If you're consistently hitting 80°C under load, your cooling needs attention. At 100°C, thermal throttling kicks in.

You can also control fan speeds:

# Install fancontrol

sudo apt-get install fancontrol

# Run the PWM configuration wizard

sudo pwmconfig

# Check fan speeds

sensors | grep fan

# fan1: 1200 RPM

# fan2: 1500 RPM

# Manually adjust fan speed (0-255, 255=100%)

echo 150 | sudo tee /sys/class/hwmon/hwmon0/pwm1

I was sick of my laptop fan screaming during builds, so I wrote a script to control fan speed based on temperature. Below 60°C, run quiet. Above 80°C, go full throttle. This hands-on control deepened my understanding of the cooling-performance tradeoff.

#!/bin/bash

# Simple temperature-based fan control script

while true; do

TEMP=$(sensors | grep 'Package id 0' | awk '{print $4}' | sed 's/+//;s/°C//')

if (( $(echo "$TEMP < 60" | bc -l) )); then

echo 100 | sudo tee /sys/class/hwmon/hwmon0/pwm1 > /dev/null

elif (( $(echo "$TEMP < 80" | bc -l) )); then

echo 180 | sudo tee /sys/class/hwmon/hwmon0/pwm1 > /dev/null

else

echo 255 | sudo tee /sys/class/hwmon/hwmon0/pwm1 > /dev/null

fi

sleep 5

done

This script checks CPU temperature every 5 seconds and adjusts fan speed accordingly. Low temps get quiet operation, high temps get maximum cooling. Running this taught me more about thermal management than reading a dozen articles.

Google, Facebook, and Amazon data centers spend 40% of their electricity bill on cooling. When you have tens of thousands of servers running 24/7, heat becomes a serious engineering challenge.

Server racks aren't randomly placed. They're arranged so cold air and hot air never mix. Cold aisles face the fronts of servers where cool air gets sucked in. Hot aisles face the backs where hot exhaust blows out. Some facilities add containment—physical barriers that separate cold and hot air completely. This design alone improves cooling efficiency by 30%+.

I once toured a data center, and stepping into the hot aisle was like entering a sauna. Easily 60°C+, almost suffocating. The cold aisle, by contrast, was like standing in front of an industrial AC unit. I needed a jacket. The temperature difference was dramatic and eye-opening.

PUE measures data center efficiency: Total Facility Power / IT Equipment Power. A PUE of 1.0 means 100% of power goes to IT equipment with zero overhead for cooling. In reality:

For example, if IT equipment draws 100kW and cooling systems draw 50kW, PUE = 1.5. Google and Facebook achieve PUE around 1.1-1.2 by using free cooling—pulling in cold outside air during winter instead of running chillers. This is why so many data centers are built in cold climates like Iceland, Finland, or northern Canada.

Large data centers deploy hundreds of temperature sensors across ceilings to generate real-time heat maps. Operators can instantly spot hot spots. If one rack runs abnormally hot, it signals potential server or fan failure. Watching these monitoring systems in action showed me that data center operations are pure engineering science.

Enthusiasts design custom loops with reservoirs, pumps, waterblocks, radiators, and tubing. Add RGB lighting and clear tubing and it's a work of art. But assembly is a nightmare. Measure tubing wrong and you get leaks. Screw up one fitting and coolant spills everywhere.

A friend built a custom loop and during first power-on, a loose fitting leaked coolant onto his graphics card. $800 down the drain. He switched back to AIO coolers after that. Beautiful but risky.

Submerge entire servers in non-conductive liquid like 3M Novec fluid or mineral oil. Heat conductivity is 1000x better than air, eliminating the need for fans. Utterly silent and incredibly efficient.

Cryptocurrency mining farms and supercomputers use this. I've seen footage of mainboards submerged in oil with bubbles rising as heat dissipates. Zero noise. Maximum efficiency.

Downside: maintenance is hell. Swapping a component requires draining the tank, cleaning the part, reinstalling, and refilling. The fluid is expensive too. Not practical for consumer use.

Overclockers chasing world records pour liquid nitrogen at -196°C directly onto CPUs. This reduces electron resistance to nearly zero, enabling clock speeds above 7GHz.

But it only lasts minutes. LN2 constantly evaporates, requiring continuous pouring. Spill it on your hand and you get frostbite. Watch overclocking competitions and you'll see people in gloves constantly refilling nitrogen. It's pure spectacle with zero practicality.

You can lower temperatures without spending a dime through undervolting. The idea: "Hey CPU, you're eating too much voltage. Let's trim it." CPUs are manufactured with voltage headroom for reliability. You can reduce this margin without losing performance.

Here's how to undervolt on Linux:

# Install intel-undervolt (Intel CPUs only)

sudo apt-get install intel-undervolt

# Edit configuration

sudo nano /etc/intel-undervolt.conf

# Example settings (reduce voltage in millivolts)

# undervolt 0 'CPU' -100

# undervolt 1 'GPU' -75

# undervolt 2 'CPU Cache' -100

# Apply settings

sudo intel-undervolt apply

# Stress test for stability

stress-ng --cpu 4 --timeout 60s

sensors

I undervolted my laptop and saw temperatures drop from 85°C to 75°C under full load. Fan noise decreased noticeably. Battery life increased by 30 minutes. Free performance gains.

But push it too far and you'll crash. Start at -100mV and increase in -10mV increments, testing stability after each step. Blue screen means you went too aggressive. Dial it back.

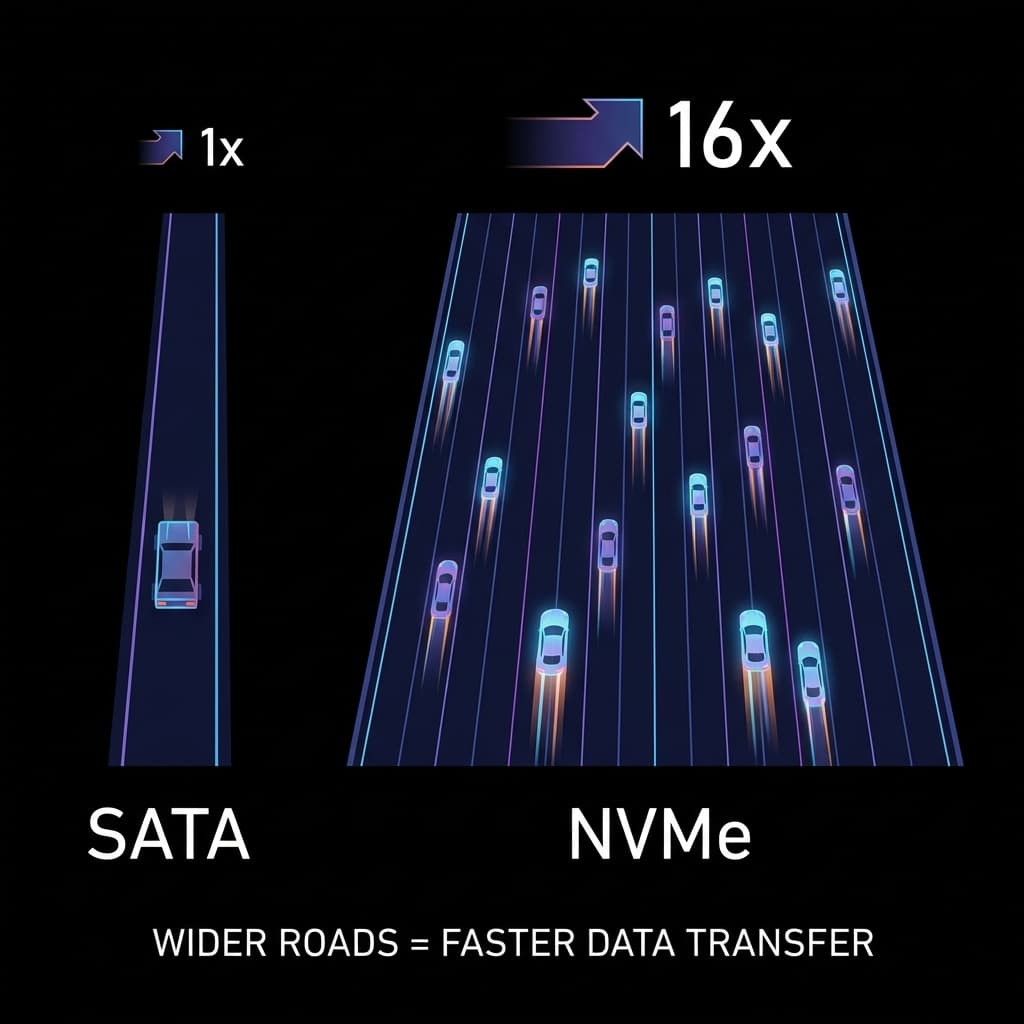

| Type | Air Cooling | Liquid Cooling |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | Air | Liquid (Coolant) |

| Noise | Loud at high RPM | Quieter (pump noise exists) |

| Risk | None (Semi-permanent) | Leak risk, pump failure |

| Price | $20-$50 (tower cooler) | $100-$250 (AIO) |

| Best For | General users, servers (reliability) | Hardcore gamers, overclockers |

Now I understand why server rooms blast AC and are filled with deafening fan noise. Leaks are catastrophic in production environments, so air cooling dominates (though immersion cooling is gaining traction). I also learned why my MacBook runs so quietly—the aluminum unibody acts as a giant heatsink. Apple minimized fans and maximized passive cooling through the chassis itself.

A: When CPU temperature exceeds safe limits (typically 100°C), the processor automatically reduces clock speed to lower heat generation and prevent physical damage. This is the #1 cause of sudden FPS drops in games or slow builds in development.

A: Fan RPM (revolutions per minute) directly affects airflow, but noise increases logarithmically with speed. A large fan (140mm) spinning slowly produces more airflow and less noise than a small fan (80mm) spinning fast. Bigger, slower fans are superior for quiet, efficient cooling.

A: For every 100kW used by IT equipment, only 10kW goes to cooling and infrastructure overhead. This is world-class efficiency. Most data centers operate at PUE 1.5-2.0. Google and AWS achieve 1.1-1.2 through aggressive optimization like free cooling and hot/cold aisle containment.

A: Heat pipes contain small amounts of liquid that evaporates at the hot end and condenses at the cold end. Capillary action circulates the fluid, enabling efficient passive heat transfer without requiring external power. They're the backbone of modern air cooling.

A: Metal surfaces are microscopically rough with air-filled gaps. Air is an excellent insulator, blocking heat transfer. Thermal paste fills these gaps, dramatically improving thermal conductivity. Without it, temperatures can spike 20°C or more.

"Cool head, warm heart." For developers, this should be literal: keep your CPU cold and your passion hot. If your machine is screaming with fan noise, maybe today's the day to clean out the dust.

Cooling isn't just about lowering temperatures. It extends component lifespan, maximizes performance, and reduces power consumption. Ever worked with a laptop on your lap and felt it get uncomfortably warm? That's insufficient cooling. Add a cooling pad or prop it up with a book to improve airflow, and you'll see temps drop significantly.

I've now fully internalized cooling principles. Conduction, convection, radiation. Thermal paste, heat pipes, radiators. The trade-offs between air and liquid cooling. Data center PUE metrics. Undervolting tricks. It all points to one goal: dissipate heat quickly, efficiently, and quietly.

Whether you're building a gaming rig, deploying servers, or just trying to keep your laptop from thermal throttling during a compile, understanding cooling is fundamental. It's not glamorous, but it's the unsung hero keeping every computer on Earth running without literally catching fire.

Now go clean that dust out of your heatsink. Your CPU will thank you.