RBAC vs ABAC: Designing Fine-Grained Access Control

Started with admin/user roles but requirements grew complex. When RBAC isn't enough, ABAC provides attribute-based fine-grained control.

Started with admin/user roles but requirements grew complex. When RBAC isn't enough, ABAC provides attribute-based fine-grained control.

A comprehensive deep dive into client-side storage. From Cookies to IndexedDB and the Cache API. We explore security best practices for JWT storage (XSS vs CSRF), performance implications of synchronous APIs, and how to build offline-first applications using Service Workers.

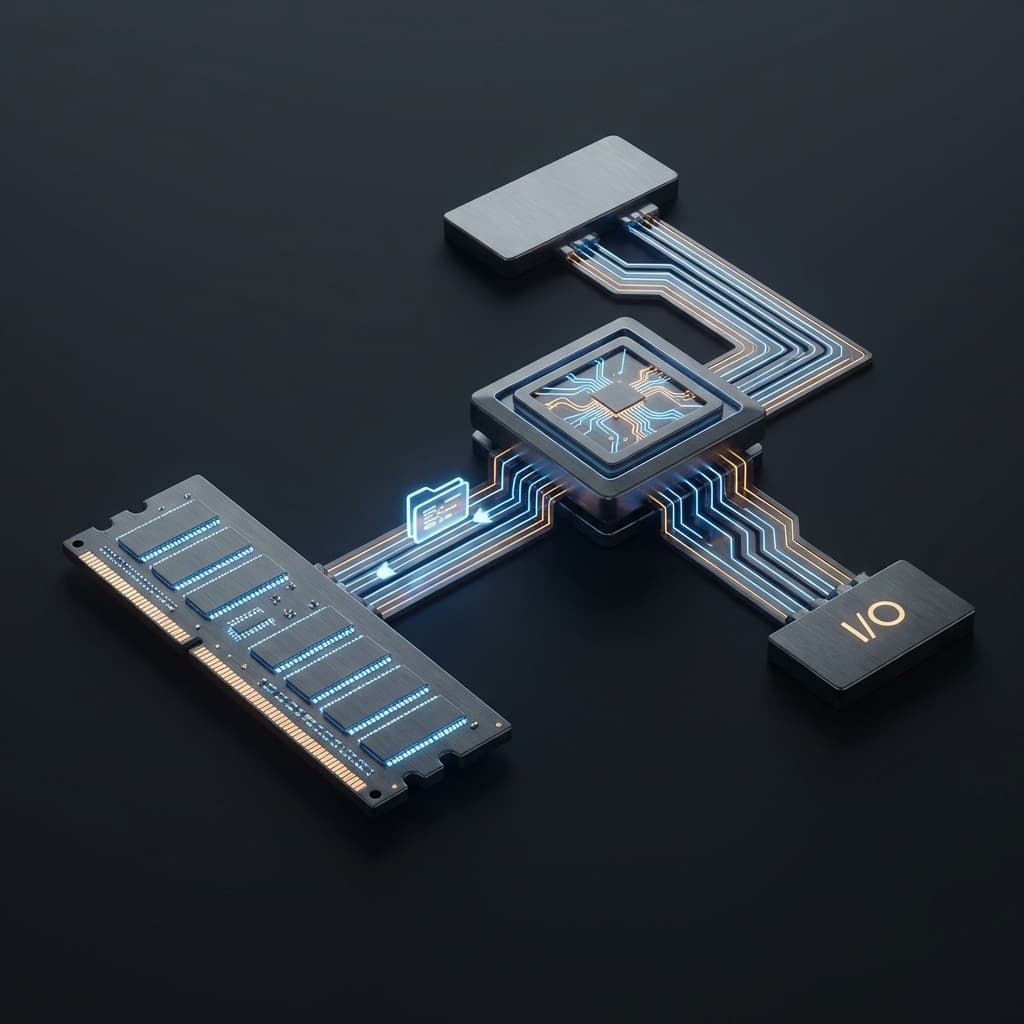

Why is the CPU fast but the computer slow? I explore the revolutionary idea of the 80-year-old Von Neumann architecture and the fatal bottleneck it left behind.

App crashes only in Release mode? It's likely ProGuard/R8. Learn how to debug obfuscated stack traces, use `@Keep` annotations, and analyze `usage.txt`.

ChatGPT answers questions. AI Agents plan, use tools, and complete tasks autonomously. Understanding this difference changes how you build with AI.

It started simple. Two roles: admin and user. Admin gets everything, user gets read-only. Clean, clear, done.

Then the real requirements came in. "Users should only be able to edit their own posts." I paused. If I give the user role 'edit post' permission, they can edit everyone's posts. If I don't, they can't edit even their own.

Roles alone couldn't express "who can access whose resources." Using a hotel key card metaphor, role-based permissions like "access all rooms on floor 3" are easy. But "only access the room I booked" is a conditional that a simple key card can't encode.

That's when the difference between RBAC (Role-Based Access Control) and ABAC (Attribute-Based Access Control) finally clicked.

Let me clear up the confusion first.

Both RBAC and ABAC are authorization methodologies.

The hotel key card metaphor is spot-on. Front desk staff get master keys (admin), housekeeping gets full floor access (manager), guests get their own room only (guest).

// RBAC structure

interface User {

id: string;

name: string;

roles: Role[]; // A user can have multiple roles

}

interface Role {

id: string;

name: string; // 'admin', 'manager', 'user'

permissions: Permission[];

}

interface Permission {

id: string;

resource: string; // 'posts', 'users', 'comments'

action: string; // 'create', 'read', 'update', 'delete'

}

You bundle permissions into roles. When a new manager joins, just assign the 'manager' role. No need to configure individual permissions.

Role hierarchy is also possible. admin > manager > user, where higher roles inherit all permissions from lower roles.

// RBAC permission check example

function canUpdatePost(user: User, post: Post): boolean {

return user.roles.some(role =>

role.permissions.some(perm =>

perm.resource === 'posts' && perm.action === 'update'

)

);

}

// Problem: This checks for update permission on ANY post

// It doesn't check "is this MY post?"

This is where the limitation shows. RBAC expresses "who can do what." It struggles with conditional permissions like "who can do what to whose resources under what conditions."

ABAC decides permissions based on attributes instead of roles. It considers user attributes, resource attributes, and environment attributes.

Think of it like bank vault access. You don't enter just because you're an "executive." You need: "executive role + business hours + your branch + two-factor auth complete." Multiple attributes must all be satisfied.

// ABAC policy example

interface Policy {

id: string;

name: string;

effect: 'allow' | 'deny';

conditions: Condition[];

}

interface Condition {

attribute: string; // 'user.id', 'resource.ownerId', 'environment.time'

operator: string; // 'equals', 'greaterThan', 'in'

value: any;

}

// "Users can only edit their own posts" policy

const editOwnPostPolicy: Policy = {

id: 'edit-own-post',

name: 'Edit Own Post',

effect: 'allow',

conditions: [

{ attribute: 'user.id', operator: 'equals', value: 'resource.authorId' },

{ attribute: 'resource.type', operator: 'equals', value: 'post' },

{ attribute: 'action', operator: 'equals', value: 'update' }

]

};

Now "edit only your own posts" is expressible. Check if user.id matches resource.authorId.

-- users table

CREATE TABLE users (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

email VARCHAR(255) UNIQUE NOT NULL,

name VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

);

-- roles table

CREATE TABLE roles (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

name VARCHAR(50) UNIQUE NOT NULL, -- 'admin', 'manager', 'user'

description TEXT,

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

);

-- permissions table

CREATE TABLE permissions (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

resource VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL, -- 'posts', 'users'

action VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL, -- 'create', 'read', 'update', 'delete'

description TEXT,

UNIQUE(resource, action)

);

-- role_permissions: assign permissions to roles

CREATE TABLE role_permissions (

role_id UUID REFERENCES roles(id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

permission_id UUID REFERENCES permissions(id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

PRIMARY KEY (role_id, permission_id)

);

-- user_roles: assign roles to users

CREATE TABLE user_roles (

user_id UUID REFERENCES users(id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

role_id UUID REFERENCES roles(id) ON DELETE CASCADE,

PRIMARY KEY (user_id, role_id)

);

This structure gives you flexible role and permission management. Add new permissions to the permissions table and connect them to the roles that need them.

Supabase's Row Level Security (RLS) is a real-world ABAC implementation. You set policies on each table to control access at the row level.

-- posts table

CREATE TABLE posts (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT gen_random_uuid(),

title VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

content TEXT NOT NULL,

author_id UUID REFERENCES users(id) NOT NULL,

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

);

-- Enable RLS

ALTER TABLE posts ENABLE ROW LEVEL SECURITY;

-- Policy 1: Anyone can read all posts

CREATE POLICY "Anyone can read posts"

ON posts FOR SELECT

TO authenticated, anon

USING (true);

-- Policy 2: Users can only update their own posts

CREATE POLICY "Users can update own posts"

ON posts FOR UPDATE

TO authenticated

USING (auth.uid() = author_id)

WITH CHECK (auth.uid() = author_id);

-- Policy 3: Users can only delete their own posts

CREATE POLICY "Users can delete own posts"

ON posts FOR DELETE

TO authenticated

USING (auth.uid() = author_id);

-- Policy 4: Admins can do anything

CREATE POLICY "Admins can do anything"

ON posts FOR ALL

TO authenticated

USING (

EXISTS (

SELECT 1 FROM user_roles ur

JOIN roles r ON ur.role_id = r.id

WHERE ur.user_id = auth.uid() AND r.name = 'admin'

)

);

The auth.uid() = author_id condition is the key. It compares the currently logged-in user ID with the post author ID. This is attribute-based judgment, the essence of ABAC.

Backend permission checks are crucial, but you also need to conditionally show UI elements on the frontend. CASL.js handles that.

import { createMongoAbility, AbilityBuilder } from '@casl/ability';

// Define user abilities

function defineAbilitiesFor(user: User) {

const { can, cannot, build } = new AbilityBuilder(createMongoAbility);

if (user.roles.includes('admin')) {

can('manage', 'all'); // Admin can do everything

} else {

can('read', 'Post');

can('create', 'Post');

can('update', 'Post', { authorId: user.id }); // Only own posts

can('delete', 'Post', { authorId: user.id }); // Only own posts

}

return build();

}

// Use in React component

function PostActions({ post, user }) {

const ability = defineAbilitiesFor(user);

return (

<div>

{ability.can('update', 'Post', { authorId: post.authorId }) && (

<button onClick={handleEdit}>Edit</button>

)}

{ability.can('delete', 'Post', { authorId: post.authorId }) && (

<button onClick={handleDelete}>Delete</button>

)}

</div>

);

}

By passing the { authorId: post.authorId } condition, you check permissions ABAC-style. Even the frontend can determine "is this my post?"

In practice, you mix both. Use RBAC for broad permissions, ABAC for fine-grained conditions.

// Hybrid permission check

async function canAccessResource(

user: User,

resource: Resource,

action: string

): Promise<boolean> {

// Step 1: RBAC check (role-based broad permissions)

const hasRolePermission = await checkRolePermission(user, resource.type, action);

if (hasRolePermission && user.roles.includes('admin')) {

return true; // Admins always pass

}

// Step 2: ABAC check (attribute-based fine-grained conditions)

const policies = await getPoliciesForAction(resource.type, action);

for (const policy of policies) {

if (evaluatePolicy(policy, user, resource)) {

return policy.effect === 'allow';

}

}

return false; // Default deny

}

In real projects, the pattern that made sense was: "Use roles for the big picture, use policies for exceptions."

RBAC is the foundation of permission management. Define roles, assign permissions, and management stays simple. But fine-grained requirements like "own resources only" or "under specific conditions" are hard to express.

ABAC judges permissions based on user, resource, and environment attributes. It's flexible but policy management can get complex.

In practice, a hybrid approach works best: RBAC for broad permissions, ABAC for exceptions and conditions. Strengthen database-level security with Supabase RLS, and control frontend UI conditionally with CASL.js. Together, they create a robust permission system.

The initial thought "won't admin/user be enough?" collapsed at the first complex requirement. But thanks to that, I gained a deeper understanding of access control design.