I Went Through Hell Switching Databases: Surviving with Hexagonal Architecture

1. "Can't We Just Rewrite the Queries?"

In the early days of my service, I kept telling myself "Faster, Faster!" as I dashed through development.

That was why we chose MongoDB as our database. Since we didn't need to define a schema in advance, we could add or remove fields whenever the product specs changed, which was incredibly convenient for a startup finding its product-market fit.

However, a year later, as the service exploded in size, the Relationships between data became crucial.

MongoDB's denormalization strategy made it increasingly difficult to maintain data integrity. As complex join queries became necessary for analytics and back-office features, performance issues started to bubble up.

Eventually, I decided to migrate to PostgreSQL to ensure ACID transactions and structured data relationships.

I confidently told myself,

"Don't worry. I'll just find all the db.collection.findOne calls in the code and replace them with SQL. It shouldn't take more than a week."

...That was my biggest miscalculation and the incantation that opened the gates of hell.

When I actually opened the code, the situation was far more terrible than I imagined.

// ❌ Example of Code from Hell (Legacy)

async function createOrder(userId, items) {

// 1. Ghost of MongoDB hiding deep within business logic

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({ _id: new ObjectId(userId) });

if (!user) throw new Error('User not found');

// 2. External API calls mixed in (Exchange rate)

const exchangeRate = await axios.get('https://api.exchangerate.com/usd-krw');

// 3. True Business Logic (Price calculation)

const order = {

_id: new ObjectId(), // Why is MongoDB ID generation logic here?

userId: user._id,

amount: items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + item.price, 0) * exchangeRate.data.rate,

createdAt: new Date()

};

// 4. Saving to DB again (MongoDB syntax)

await db.collection('orders').insertOne(order);

// 5. Even sending email...

await sendgrid.send({ to: user.email, text: 'Order Complete' });

}

In this single function, business logic, DB access (MongoDB dependency), External API (Exchange Rate), and Email sending were mixed together like Bibimbap.

MongoDB-specific codes like ObjectId, findOne, insertOne were embedded deep into the business logic, so changing the DB meant "Rewriting the code from scratch".

What about tests? Of course, since they were written connecting directly to the DB, switching the DB meant all tests would fail.

In despair, I was googling when I encountered Hexagonal Architecture, also known as the Ports and Adapters pattern.

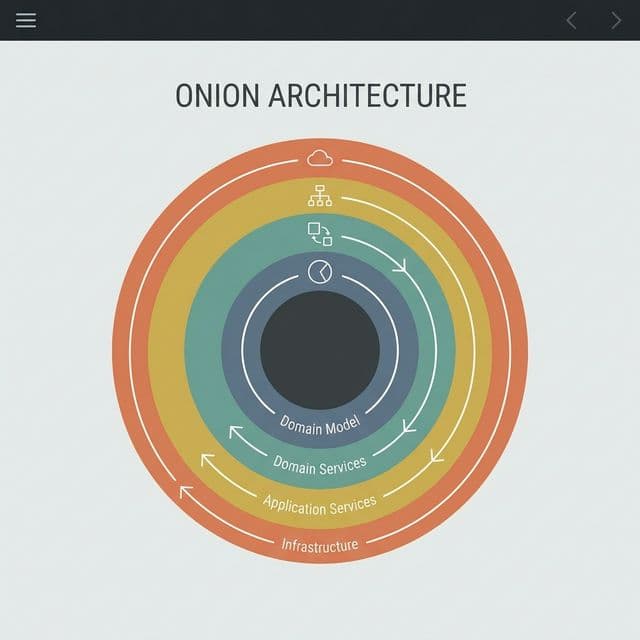

2. Protect the Donut Hole: The Core Concept

The core philosophy of Hexagonal Architecture is remarkably simple.

"Keep the precious things in the center, and push the changeable things to the outside."

It's called Hexagonal because diagrams often draw it as a hexagon, but I prefer to compare it to a "Donut".

- Center (Core, Donut Dough): Our Business Logic (Order calculation, Discount application, Inventory check, etc.). Core value that must never change.

- Outside (Out, Topping/Sugar): DB, UI, External APIs, Frameworks. Tools that can change anytime.

We eat donuts for the delicious dough (business logic), not for the sugar on the outside (DB).

Just because we switch the sugar topping to chocolate, the donut shouldn't turn into a bagel, right?

But in my code, the sugar (MongoDB) was mixed into the dough (Business Logic), so trying to remove the sugar meant crumbling the entire bread.

3. Port: "We Need These Features"

The first step of refactoring was drawing boundaries.

The first thing I did was define the window through which business logic talks to the outside world, that is, the Interface (Port).

It's like declaring, "I don't care if you are MongoDB or Postgres, I just need save and findById capabilities."

// core/ports/OrderRepository.ts (Inside the Donut)

// Interface is pure TypeScript syntax, so it doesn't depend on any specific DB.

export interface OrderRepository {

save(order: Order): Promise<void>;

findById(id: string): Promise<Order | null>;

findAllByUserId(userId: string): Promise<Order[]>;

}

// core/ports/EmailPort.ts

export interface EmailPort {

sendConfirmation(email: string, message: string): Promise<void>;

}

These interface files are pure TypeScript files. You can't find import mongo or import pg anywhere even if you wash your eyes and look.

This is the beginning of Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP).

Business logic now depends only on abstract interfaces, not concrete DB technologies.

4. Adapter: "I'll Fit In"

Now we create Adapters that implement these interfaces. This is the area outside the donut, the Infrastructure layer.

This is where we shove the dirty(?) DB connection codes or API call codes.

// infrastructure/adapters/PostgresOrderRepository.ts (Outside the Donut)

import { Pool } from 'pg'; // Only here do we use the pg library!

import { OrderRepository } from '../../core/ports/OrderRepository';

export class PostgresOrderRepository implements OrderRepository {

constructor(private db: Pool) {}

async save(order: Order): Promise<void> {

// Dirty SQL queries go here.

// Converting Domain Object (Order) to DB Schema also happens here.

const query = 'INSERT INTO orders (id, user_id, amount, created_at) VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4)';

const values = [order.id, order.userId, order.amount, order.createdAt];

await this.db.query(query, values);

}

async findById(id: string): Promise<Order | null> {

const res = await this.db.query('SELECT * FROM orders WHERE id = $1', [id]);

if (res.rows.length === 0) return null;

return this.mapToDomain(res.rows[0]); // Convert DB data to Domain Object

}

}

Now the business logic doesn't even know PostgresOrderRepository exists. It only talks to the shell called OrderRepository.

Want to change DB again later? Just make a MySqlOrderRepository and swap it. Business logic doesn't need a single line of change.

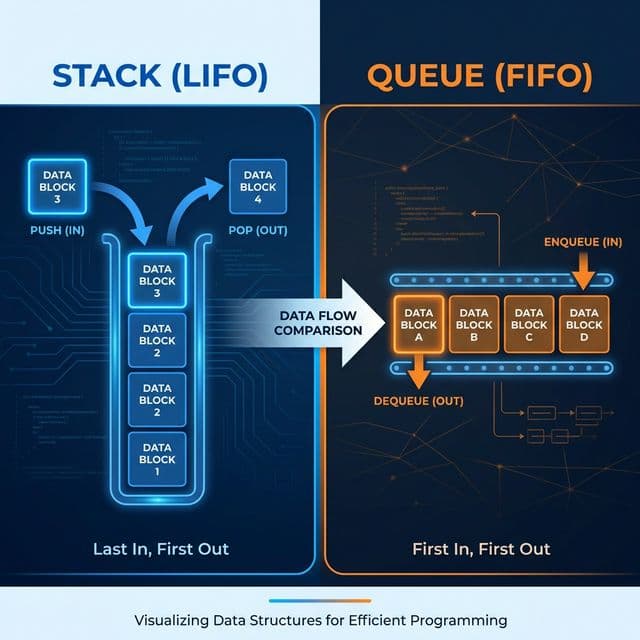

5. DTO Mapping: "Show Your Passport at the Border"

Doing Hexagonal Architecture involves a task that is annoying but essential. That is Data Mapping.

When a request comes from outside (Web Request) or data comes from DB (DB Entity) into the Domain area (Core), it must change clothes into a form the Domain understands (DTO).

Example of Structured Folder Organization

src/

├── core/ # 🟢 Inside Donut (Business Logic)

│ ├── domain/ # Core Domain Models (Order, User, etc.)

│ ├── ports/ # Interface Definitions (OrderRepository, EmailPort)

│ └── service/ # Logic Implementation (OrderService)

│

└── infrastructure/ # 🔴 Outside Donut (Technical Implementation)

├── adapters/ # Port Implementations (PostgresRepo, SendGridAdapter)

├── database/ # DB Connection Config

├── web/ # Express/NestJS Controllers

└── dtos/ # Data Transfer Objects

Even at the Controller level, strictly speaking, user input shouldn't go directly into Domain Objects but should be received as DTOs (Data Transfer Objects) like CreateOrderRequest, validated, and then passed to the Service.

This prevents the disaster where "Adding a column to a DB table" forces you to modify "Business Logic Classes". It effectively isolates changes.

6. Dependency Injection (DI): Who Assembles It?

So, we made ports and adapters. Who connects them?

OrderService is shouting that it needs an OrderRepository interface, and PostgresOrderRepository is ready.

We need a matchmaker to link these two. This is Dependency Injection (DI).

If you use a framework like NestJS, it's very easy.

// app.module.ts (NestJS Example)

@Module({

providers: [

OrderService,

{

provide: 'OrderRepository', // Interface Name (Token)

useClass: PostgresOrderRepository, // Actual Implementation

},

],

})

export class AppModule {}

If you use Vanilla Node.js without a framework, you can assemble it manually in the entry file (main.ts).

// main.ts

const dbPool = new Pool(...);

const orderRepo = new PostgresOrderRepository(dbPool); // Create Adapter

const emailService = new SendGridEmailService(apiKey);

// Inject Adapter into Service (Plug in)

const orderService = new OrderService(orderRepo, emailService);

// Now start server

server.start(orderService);

The completion of Hexagonal comes when you only mention concrete classes (Postgres...) in the entry point main.ts, and make specific logic solely look at interfaces. This centralization of dependency configuration is key to maintainability.

7. Heaven of Testing

The real charm of this structure explodes in Testing.

Before, to test a single order creation logic, I had to spin up local MongoDB, insert/delete data... executing tests took 10 seconds. It was slow and painful.

Now, I can just create a Mock Adapter and test.

// tests/InMemoryOrderRepo.ts

// Fake implementation storing in memory array without DB

class InMemoryOrderRepo implements OrderRepository {

private orders: Order[] = [];

async save(order: Order) {

this.orders.push(order);

}

async findById(id: string) {

return this.orders.find(o => o.id === id) || null;

}

}

test('Order Creation Test', async () => {

const fakeRepo = new InMemoryOrderRepo();

const service = new OrderService(fakeRepo, new FakeEmailService());

await service.createOrder('user1', [item1]);

// Can verify "Save" was called without a DB!

expect(fakeRepo.orders.length).toBe(1);

});

Tests run in less than 0.1 seconds. Because there is no DB. No network usage.

Thanks to this, I could actually practice TDD (Test Driven Development) instead of just pretending. I could run hundreds of test cases in seconds, giving me immediate feedback on my logic.

8. But There Are Downsides (No Silver Bullet)

Of course, Hexagonal Architecture isn't unconditional truth. Here are the downsides I felt deeply.

- Files Triple: Interface files, implementation files, DTO files... for a simple CRUD app, it's a massive over-investment. You might feel like you are writing more boilerplate than actual logic.

- Complex Structure: Junior devs ask, "Why simply

db.save()? Why complicate with port and adapter?" There is a high cost of explaining design intent and onboarding new team members.

- Boilerplate Code: Converting data from DB format to Domain format, Domain to DTO... writing mapping code makes you feel like "Am I a mapping machine?" It can be tedious.

So I only apply this architecture to "Projects where core business logic is complex and needs long-term maintenance."

For simple admin pages or one-off event sites, I just code quickly with MVC pattern. (That's better for mental health.)

9. Conclusion: How to Pay Off Technical Debt

The database migration was eventually successful.

By severing the dependencies of spaghetti code with Hexagonal Architecture and plugging in a new PostgreSQL adapter, we transitioned smoothly without major accidents.

Now, even if the Exchange Rate API changes or Email Service switches, I'm not afraid. I just need to make another adapter and swap it.

We often ignore design with the excuse "We need to develop fast."

But that "speed" later returns as a massive "Technical Debt" holding us back.

If your project is turning into spaghetti, or if you fear external system changes, stop for a moment and consider adopting Hexagonal Architecture.

The solid stability that "No matter how the outside world changes, our core logic remains unshaken" will save you from overtime work.

title_en: "I Went Through Hell Switching Databases: Surviving with Hexagonal Architecture"

description: "서비스 초기, MongoDB를 쓰다가 RDB로 마이그레이션 해야 할 순간이 왔습니다. 하지만 비즈니스 로직과 DB 코드가 뒤엉켜 있어 지옥을 경험했죠. 헥사고날 아키텍처(포트와 어댑터)를 도입하여 비즈니스 로직을 순수하게 지켜내고, 기술 부채로부터 탈출한 경험을 공유합니다."

description_en: "When our service grew, migrating from MongoDB to PostgreSQL became inevitable. But our code was a spaghetti mess of business logic and database queries. I share my journey of adopting Hexagonal Architecture (Ports and Adapters) to decouple the core logic from external tools, turning a nightmare migration into a manageable task."

date: "2025-08-20"

tags: ["Architecture", "Hexagonal Architecture", "Clean Code", "Refactoring", "Design Patterns"]

category: "architecture"

published: true

coverImage: "/images/blog/hexagonal-architecture/cover.png"

1. "그냥 쿼리만 바꾸면 되는 거 아냐?"

서비스 초기, 저희는 빠르게 개발하기 위해 MongoDB를 선택했습니다. 스키마가 없으니 자유롭게 데이터를 넣고 뺄 수 있어서 편했죠.

하지만 1년 뒤, 데이터 간의 관계가 복잡해지면서 PostgreSQL로 마이그레이션 해야 할 순간이 왔습니다.

저는 속으로 자신 있게 생각했습니다.

"뭐, 코드에서 db.collection.findOne 같은 것만 찾아서 SQL로 바꾸면 금방 끝나겠는데요?"

...그건 저의 가장 큰 오산이었습니다.

막상 코드를 열어보니 상황은 심각했습니다.

// ❌ 지옥의 코드 예시

async function createOrder(userId, items) {

// 1. 비즈니스 로직 사이에 숨어있는 MongoDB의 망령

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({ _id: new ObjectId(userId) });

if (!user) throw new Error('User not found');

// 2. 외부 API 호출도 섞여 있음

const exchangeRate = await axios.get('https://api.exchangerate.com/usd-krw');

const order = {

_id: new ObjectId(), // MongoDB ID 생성

userId: user._id,

amount: items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + item.price, 0) * exchangeRate.data.rate, // 비즈니스 로직

createdAt: new Date()

};

// 3. 다시 DB 저장

await db.collection('orders').insertOne(order);

// 4. 이메일 발송까지...

await sendgrid.send({ to: user.email, text: '주문 완료' });

}

이 함수 하나에 비즈니스 로직, DB 접근, 외부 API 호출, 이메일 발송이 비빔밥처럼 섞여 있었습니다.

DB를 바꾸려면 이런 함수 수십 개를 처음부터 다시 짜야 했습니다. 테스트 코드는요? 당연히 다 깨집니다.

이때 헥사고날 아키텍처(Hexagonal Architecture), 다른 말로 포트와 어댑터(Ports and Adapters) 패턴을 만났습니다.

2. 도넛 구멍을 지켜라

헥사고날 아키텍처의 핵심 철학은 "소중한 것은 가운데에 두고, 변하기 쉬운 것은 바깥으로 밀어내라"입니다.

- 가운데 (Core): 우리의 비즈니스 로직 (주문 계산, 할인 적용 등). 절대 변하지 않아야 함.

- 바깥 (Out): DB, UI, 외부 API. 언제든 바뀔 수 있음.

저는 이걸 "도넛"에 비유하고 싶습니다.

우리가 먹고 싶은 건 도넛의 빵(비즈니스 로직)이지, 겉에 묻은 설탕(DB)이나 포장지(UI)가 아닙니다.

설탕을 초콜릿으로 바꾼다고 해서 도넛이 베이글이 되면 안 되잖아요?

3. 포트(Port): "우리는 이런 기능이 필요해요"

가장 먼저 한 일은 비즈니스 로직이 외부와 대화하는 인터페이스(Port)를 정의하는 것이었습니다.

"나는 네가 MongoDB인지 Postgres인지는 관심 없고, 그냥 save랑 findById만 있으면 돼."라고 선언하는 거죠.

// ports/OrderRepository.ts (도넛 안쪽)

export interface OrderRepository {

save(order: Order): Promise<void>;

findById(id: string): Promise<Order | null>;

}

// ports/EmailService.ts

export interface EmailService {

sendConfirmation(email: string): Promise<void>;

}

이 인터페이스들은 순수한 TypeScript 파일입니다. import mongo 같은 건 전혀 없습니다.

이게 바로 의존성 역전(DIP)의 시작입니다.

4. 어댑터(Adapter): "제가 맞춰드릴게요"

이제 인터페이스를 구현하는 어댑터(Adapter)를 만듭니다. 이건 도넛 바깥쪽 영역입니다.

여기에 더러운(?) DB 코드나 API 코드를 몰아넣습니다.

// adapters/PostgresOrderRepository.ts (도넛 바깥쪽)

import { Pool } from 'pg';

export class PostgresOrderRepository implements OrderRepository {

constructor(private db: Pool) {}

async save(order: Order): Promise<void> {

// 여기에 지저분한 SQL 쿼리가 들어갑니다

await this.db.query('INSERT INTO orders ...', [order.id, ...]);

}

async findById(id: string): Promise<Order | null> {

const res = await this.db.query('SELECT * ...');

return this.mapToDomain(res.rows[0]);

}

}

이제 비즈니스 로직은 PostgresOrderRepository의 존재를 모릅니다. 그저 OrderRepository라는 껍데기와 대화할 뿐이죠.

나중에 DB를 바꾸고 싶으면? MongoOrderRepository를 만들어서 갈아 끼우기만 하면 됩니다.

5. 비즈니스 로직의 순수성 회복

이제 아까 그 지옥 같던 createOrder 함수를 청소해 봅시다.

// core/OrderService.ts (도넛 안쪽)

export class OrderService {

constructor(

private orderRepo: OrderRepository, // 인터페이스 주입!

private emailService: EmailService

) {}

async createOrder(userId: string, items: Item[]) {

// 1. 순수한 비즈니스 로직만 남음

const order = Order.create(userId, items);

// 2. 포트를 통해 저장 (구현체는 모름)

await this.orderRepo.save(order);

// 3. 포트를 통해 발송

await this.emailService.sendConfirmation(userId);

}

}

코드가 아름다워졌습니다.

collection이니 findOne이니 하는 DB 용어가 싹 사라졌습니다. 오직 "주문 생성", "저장", "발송"이라는 비즈니스 언어만 남았습니다.

6. 테스트의 천국

이 구조의 진짜 매력은 테스트에서 터집니다.

예전에는 주문 생성 로직 하나 테스트하려면 로컬에 DB 띄우고, 데이터 넣었다 뺐다... 엄청 느리고 힘들었죠.

이제는 가짜 어댑터(Mock Adapter)를 만들어서 테스트하면 됩니다.

// 테스트용 가짜 DB

class InMemoryOrderRepo implements OrderRepository {

private orders = [];

async save(order) { this.orders.push(order); }

async findById(id) { return this.orders.find(o => o.id === id); }

}

test('주문 생성 테스트', async () => {

const fakeRepo = new InMemoryOrderRepo();

const service = new OrderService(fakeRepo, ...);

await service.createOrder('user1', []);

// DB 없이도 "저장"이 호출됐는지 확인 가능!

expect(fakeRepo.orders.length).toBe(1);

});

테스트 속도가 0.1초도 안 걸립니다. DB가 없으니까요.

이 덕분에 TDD(테스트 주도 개발)를 제대로 할 수 있게 되었습니다.

7. 하지만 단점도 있다 (은탄환은 없다)

물론 헥사고날 아키텍처가 무조건 정답은 아닙니다. 제가 느낀 단점은 이렇습니다.

- 파일이 3배로 늘어난다: 인터페이스 만들고, 구현체 만들고, DTO 변환하고... 간단한 CRUD 앱에는 과투자가 될 수 있습니다.

- 구조가 복잡하다: 신입 개발자가 오면 "그냥 저장하면 되지 왜 interface를 거쳐요?"라고 물어봅니다. 설계 의도를 설명하는 비용이 듭니다.

- 데이터 변환 비용: DB 모델과 도메인 모델을 분리하다 보니, 데이터를 읽어올 때마다 매핑(Mapping)하는 과정이 필요합니다.

그래서 저는 "핵심 비즈니스 로직이 복잡한 경우"에만 이 아키텍처를 적용합니다. 단순한 게시판 댓글 기능 같은 건 그냥 합니다.

8. 마치며: 기술 부채를 갚는 방법

데이터베이스 마이그레이션은 결국 성공했습니다.

기존 코드의 의존성을 끊어내고, 새 어댑터를 끼우는 방식으로 진행했더니 큰 사고 없이 PostgreSQL로 넘어갈 수 있었습니다.

우리는 종종 "빨리 개발해야 하니까"라는 핑계로 설계를 무시합니다.

하지만 그 "빠름"이 나중에는 발목을 잡는 '기술 부채'가 되어 돌아옵니다.

여러분도 프로젝트가 점점 스파게티가 되어간다면, 잠시 멈추고 헥사고날 아키텍처를 도입해 보세요.

"외부 세상이 아무리 변해도, 우리의 핵심 로직은 흔들리지 않는다"는 안정감을 느낄 수 있을 겁니다.

I Went Through Hell Switching Databases: Surviving with Hexagonal Architecture

1. "Can't We Just Rewrite the Queries?"

In the early days of our service, we chose MongoDB for rapid development. The schemaless nature allowed us to insert and retrieve data freely, which was convenient.

However, a year later, as data relationships became complex, the moment came to migrate to PostgreSQL.

I confidently told my team,

"Well, we just need to find db.collection.findOne calls and replace them with SQL, right? It won't take long."

...That was my biggest miscalculation.

When I opened the code, the situation was dire.

// ❌ Example of Code from Hell

async function createOrder(userId, items) {

// 1. Ghost of MongoDB hiding in business logic

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({ _id: new ObjectId(userId) });

if (!user) throw new Error('User not found');

// 2. External API calls mixed in

const exchangeRate = await axios.get('https://api.exchangerate.com/usd-krw');

const order = {

_id: new ObjectId(), // MongoDB ID generation

userId: user._id,

amount: items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + item.price, 0) * exchangeRate.data.rate, // Business Logic

createdAt: new Date()

};

// 3. Saving to DB again

await db.collection('orders').insertOne(order);

// 4. Even sending email...

await sendgrid.send({ to: user.email, text: 'Order Complete' });

}

In this single function, business logic, DB access, external API calls, and email sending were mixed like Bibimbap.

To change the DB, I had to rewrite dozens of such functions from scratch. And the test codes? Of course, they all broke.

That's when I encountered Hexagonal Architecture, also known as Ports and Adapters pattern.

2. Protect the Donut Hole

The core philosophy of Hexagonal Architecture is "Keep the precious things in the center, and push the changeable things to the outside."

- Center (Core): Our Business Logic (calculating orders, applying discounts). Must never change.

- Outside (Out): DB, UI, External APIs. Can change anytime.

I like to compare this to a "Donut".

What we want to eat is the donut dough (business logic), not the sugar on the outside (DB) or the packaging (UI).

Just because we switch sugar to chocolate, the donut shouldn't turn into a bagel, right?

3. The Port: Defining the "What", Ignoring the "How"

The first step of the refactoring was drawing strict boundaries.

in Hexagonal Architecture, the core logic defines "Interfaces" (Ports) for everything it needs from the outside world.

It's like declaring:

"I don't care if you use MongoDB, PostgreSQL, or even a text file. I just need a way to save an order and findById."

3.1. Repository Port (Output Port)

// core/ports/OrderRepository.ts (Inside the Donut - Core)

// This interface is pure TypeScript. No DB dependencies allowed.

export interface OrderRepository {

// Save the order state.

// Notice we use the Domain Entity 'Order', not a DB Schema.

save(order: Order): Promise<void>;

// Retrieve an order by ID.

findById(id: string): Promise<Order | null>;

// Find all orders for a specific user.

findAllByUserId(userId: string): Promise<Order[]>;

}

3.2. Service Port (Input Port / Use Case)

We also define how the outside world (UI, API) talks to us.

// core/ports/OrderUseCase.ts

export interface OrderUseCase {

createOrder(command: CreateOrderCommand): Promise<Order>;

cancelOrder(orderId: string): Promise<void>;

}

These interface files are pure. You won't find import mongoose or import typeorm here.

This complies with the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP): High-level modules (Business Logic) should not depend on low-level modules (DB). Both should depend on abstractions.

4. The Adapter: "I Will Adapt to Your Needs"

Now we create Adapters that implement these interfaces. This sits in the Infrastructure Layer (Outside the Donut).

This is where the "dirty" technical details live—SQL queries, HTTP calls, AWS SDKs.

4.1. PostgreSQL Adapter

// infrastructure/adapters/PostgresOrderRepository.ts (Outside the Donut)

import { Pool } from 'pg'; // Only here do we import the specific driver!

import { OrderRepository } from '../../core/ports/OrderRepository';

import { OrderMapper } from '../mappers/OrderMapper';

export class PostgresOrderRepository implements OrderRepository {

constructor(private db: Pool) {}

async save(order: Order): Promise<void> {

// 1. Convert Domain Entity to DB Schema (DTO)

const entity = OrderMapper.toPersistence(order);

// 2. Execute dirty SQL

const query = `

INSERT INTO orders (id, user_id, amount, status, created_at)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4, $5)

ON CONFLICT (id) DO UPDATE SET status = $4

`;

const values = [entity.id, entity.userId, entity.amount, entity.status, entity.createdAt];

await this.db.query(query, values);

}

async findById(id: string): Promise<Order | null> {

const res = await this.db.query('SELECT * FROM orders WHERE id = $1', [id]);

if (res.rows.length === 0) return null;

// 3. Convert DB Schema back to Domain Entity

return OrderMapper.toDomain(res.rows[0]);

}

}

Now the Business Logic doesn't even know PostgresOrderRepository exists. It only talks to the generic OrderRepository.

If we want to switch to MySQL later? We just create MysqlOrderRepository and swap it in the dependency injection container. The Business Logic relies on the contract, not the implementation.

5. DTO Mapping: The Cost of Purity

Adopting Hexagonal Architecture comes with a price: Boilerplate.

Since the Core doesn't know about the DB structure, we can't just pass database rows around. We must convert them.

- Request DTO: Incoming JSON from API -> Converted to Command Object.

- Domain Entity: The pure business object.

- Persistence DTO: The object that represents a DB row.

The Mapper Pattern

// infrastructure/mappers/OrderMapper.ts

export class OrderMapper {

static toDomain(row: any): Order {

// Reconstruct the domain object from raw DB data

return new Order({

id: row.id,

userId: row.user_id, // Snake_case to camelCase

amount: new Money(row.amount), // Value Object

status: row.status as OrderStatus,

createdAt: new Date(row.created_at)

});

}

static toPersistence(order: Order): any {

// Flatten domain object for the DB

return {

id: order.id,

user_id: order.userId,

amount: order.amount.getValue(),

status: order.status,

created_at: order.createdAt

};

}

}

This mapping layer acts as a Border Control. It ensures that no "Database Concerns" (like weird column names or specific types) leak into the clean Domain logic.

6. Dependency Injection: The Glue

We have the Interface (Port) and the Implementation (Adapter). Who connects them?

We need a Dependency Injection (DI) container.

In pure Node.js, it looks like this:

// main.ts (The Composition Root)

import { Pool } from 'pg';

import { OrderService } from './core/services/OrderService';

import { PostgresOrderRepository } from './infrastructure/adapters/PostgresOrderRepository';

import { SendGridEmailAdapter } from './infrastructure/adapters/SendGridEmailAdapter';

async function bootstrap() {

// 1. Initialize Infrastructure

const dbPool = new Pool({ connectionString: process.env.DB_URL });

// 2. Create Adapters

const orderRepo = new PostgresOrderRepository(dbPool);

const emailAdapter = new SendGridEmailAdapter(process.env.API_KEY);

// 3. Inject Adapters into the Service (Core)

// The Service expects interfaces, we pass implementations.

const orderService = new OrderService(orderRepo, emailAdapter);

// 4. Start the Application

const server = new HTTPServer(orderService);

await server.listen(3000);

}

bootstrap();

Only the bootstrap function knows about the concrete classes. The rest of the application lives in blissfull ignorance of the database technology.

7. The Ultimate Benefit: Testing Heaven

The real ROI of this architecture is Testing.

Before, testing createOrder meant spinning up a Docker container with MongoDB, seeding data, running the test, and cleaning it up. Slow and flaky.

Now? We use Fakes.

// tests/fakes/InMemoryOrderRepository.ts

// A simple array-based implementation for testing

export class InMemoryOrderRepository implements OrderRepository {

private orders: Map<string, Order> = new Map();

async save(order: Order): Promise<void> {

this.orders.set(order.id, order);

}

async findById(id: string): Promise<Order | null> {

return this.orders.get(id) || null;

}

}

// core/services/OrderService.spec.ts

test('should create an order successfully', async () => {

// Arrange

const fakeRepo = new InMemoryOrderRepository();

const fakeEmail = new FakeEmailAdapter();

const service = new OrderService(fakeRepo, fakeEmail);

// Act

await service.createOrder('user-123', items);

// Assert

const savedOrder = await fakeRepo.findById(generatedId);

expect(savedOrder).toBeDefined();

expect(savedOrder.amount).toBe(1000);

});

These tests run in milliseconds.

Because they test pure logic without touching the file system or network.

This enables true TDD (Test-Driven Development).

8. When to Use (and When NOT to)

Hexagonal Architecture is not a Silver Bullet.

Cons

- Complexity: It requires more boilerplate (Ports, Adapters, Mappers, DTOs).

- Learning Curve: Newcomers might ask "Why can't I just call the DB directly in the controller?"

- Over-engineering: For a simple CRUD app or a prototype, this is overkill.

Pros

- Maintainability: Business logic is isolated and protected.

- Testability: You can test the core logic without infrastructure.

- Flexibility: agonizing over "RabbitMQ vs Kafka"? Just define a

MessagePort and decide the implementation later.

I recommend this for Long-term projects with complex business rules.

For a hackathon or a simple admin dashboard? Stick to MVC.

9. Folder Structure Deep Dive

A common question is: "So where do I put my files?"

Here is the folder structure I use for my Node.js (NestJS/Express) projects.

src/

├── core/ # Inside the Donut (Pure Business Logic)

│ ├── entities/ # Domain Objects (Order, User)

│ ├── ports/ # Interfaces (OrderRepository, EmailService)

│ ├── services/ # Use Cases (OrderService)

│ └── exceptions/ # Domain Exceptions (OrderNotFoundException)

│

├── infrastructure/ # Outside the Donut (Adapters)

│ ├── adapters/ # Implementations

│ │ ├── persistence/ # Database Adapters (TypeORM, Mongoose)

│ │ └── external/ # 3rd Party APIs (Stripe, SendGrid)

│ ├── config/ # Environment Variables

│ └── mappers/ # DTO <-> Entity Converters

│

├── interface/ # Driving Adapters (Entry Points)

│ ├── http/ # REST Controllers

│ ├── graphql/ # Resolvers

│ └── cron/ # Scheduled Jobs

│

└── main.ts # Application Bootstrap (Dependency Injection)

Key Takeaways

- Core depends on nothing: The

core folder should verify that it has Zero dependencies on infrastructure or interface.

- Mappers are the border patrol: Never use an Entity in a Controller. Never use a DB Schema in a Service. Always map.

- Ports are the contract: If you want to know what the application does, look at the

services and ports. If you want to know how it does it, look at adapters.

[!TIP]

Start Small: You don't need all these folders from day one. Start with core and infrastructure. Split them further only when the complexity hurts. Premature optimization is the root of all evil, and premature architecture is the root of all confusion.

10. Conclusion: Breaking Free from the "DB-First" Mindset

Refactoring to Hexagonal Architecture allowed us to migrate from MongoDB to PostgreSQL with Zero downtime and Zero logic bugs.

We simply built a new Adapter, tested it against the contract, and swapped it in.

We often start projects by designing the Database Schema first. "What tables do we need?"

Hexagonal Architecture forces you to think: "What Behavior do we need?"

If your code feels like it's glued to the database, or if you are afraid to touch legacy code because "it might break something else", try drawing a hexagon.

Protect your core. Push the details to the edge.

That peace of mind is worth every extra file you create.