Clean Architecture: The Dependency Rule and Separation of Concerns

1. Don't Be a Slave to Frameworks

When starting a project, we often say: "We are building a Django app" or "This is a React project."

Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob) argues that this is fundamentally wrong.

"Architecture is not about frameworks. Architecture is about intentions."

A good architecture screams its purpose. When you look at the folder structure of a library management system, it should look like "Books, Members, Loans," not "Controllers, Views, Models."

Frameworks (Spring, Rails, React) are just details. They are tools to interact with the mechanism, but they should not dictate the structure of your business rules.

If your architecture is coupled to a framework, you are a slave to it. When the framework changes versions or becomes obsolete, your entire system dies.

Clean Architecture is about organizing your code so that the business logic is the master, and the framework is just a tool.

2. The Dependency Rule

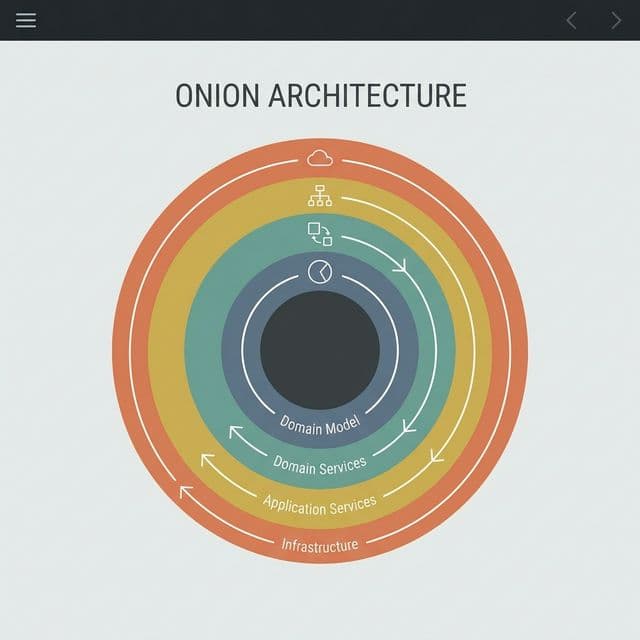

The most important concept in Clean Architecture is the Dependency Rule, visualized by concentric circles.

Rule: Source code dependencies must only point INWARD, towards higher-level policies.

- Inner Circles: Policies, High-level Business Rules, Entities. (Stable)

- Outer Circles: Mechanisms, I/O, UI, DB, Frameworks, Web. (Volatile)

Nothing in an inner circle can know anything at all about something in an outer circle.

The name of a database, the format of a web request, the HttpServletRequest object, or the structure of a JSON response should not appear in the inner circles. This is absolute.

3. The Layers

Usually, it consists of 4 layers, but you can have more. The principle matters more than the number.

3.1. Entities (The Core)

- Encapsulate Enterprise-wide Business Rules.

- Entities are plain objects (POJOs in Java) with methods. Use simplest data structures.

- They are the least likely to change when something external changes. (e.g., Changing page navigation or security security doesn't change what a "Loan" entity is).

3.2. Use Cases (Application Business Rules)

- Encapsulate Application-specific Business Rules.

- They implement all the use cases of the system (e.g., "Create Order", "Add Friend").

- They orchestrate the flow of data to and from the entities.

- They assume data is provided by a generic repository interface, knowing nothing about SQL or external APIs.

3.3. Interface Adapters

- This is the translation layer.

- It converts data from the format most convenient for the use cases and entities, to the format most convenient for some external agency like the Database or the Web.

- This layer contains the Controllers (input), Presenters (output), and Gateways (JPA/ORM implementations).

- Models here are data structures like DTOs (Data Transfer Objects).

3.4. Frameworks & Drivers (The Edge)

- The outermost layer.

- Composed of frameworks and tools such as the Database, the Web Framework (Spring MVC, Express), the UI (React).

- We don't write much code here, other than Glue Code that connects the circles.

4. How to Cross Boundaries (DIP)

A common question: "If the Use Case (Inner) needs to save data to the Database (Outer), it must call the database. Doesn't that violate the Inward Dependency Rule?"

Yes, simply calling it would violate the rule. That's why we use the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP).

- Define an Interface in the Inner Circle: The Use Case layer defines an interface called

UserRepository with a method save(User).

- Implement in the Outer Circle: The Database layer (Interface Adapter) implements this interface with

UserRepositoryImpl which contains the actual SQL logic.

- Polymorphism: At runtime, the implementation instance is injected into the Use Case.

The source code dependency points Inward (Impl depends on Interface), even though the flow of control points Outward (Use Case calls Repo). This inversion is the key to decoupling.

5. Screaming Architecture

If you look at the top-level directory of your project, what does it tell you?

If it says controllers, models, views, it's screaming "MVC Framework!". It tells you nothing about what the application does.

If it says create_order, manage_inventory, calculate_payroll, it's screaming "Order Management System!".

This is the goal. Your architecture should tell developers what the system does, not what framework it uses.

6. The Evolution and Critique

Clean Architecture is not the first of its kind. It is an evolution of:

- Hexagonal Architecture (Ports and Adapters) by Alistair Cockburn: Focuses on swapping the external world.

- Onion Architecture by Jeffrey Palermo: Focuses on the domain model core.

Some critics argue that Clean Architecture can lead to "Lasagna Code" (too many layers) and "Anemic Domain Models" if not applied carefully.

In languages like Go or Rust, strict adherence to these layers can feel unnatural compared to Java.

However, the principles—Separation of Concerns and Dependency Rule—remain universally valuable.

7. The Testability Benefit

One of the biggest wins is Testability.

Because the Use Cases are plain objects that don't depend on the UI or Database:

- You can write Unit Tests for them that run in milliseconds.

- You don't need to spin up a web server or a Docker container to test your business logic.

- You can mock the

UserRepository interface easily.

This encourages Test-Driven Development (TDD) and results in a much more robust and bug-free system.

8. FAQ: Common Questions

Q: Where do I put utility functions?

If they are pure functions (e.g., Date formatting), they can go in the Entity or Use Case layer. If they depend on libraries, put them in outer layers.

Q: Can I skip layers?

"Strict Layers" mode says no. "Relaxed Layers" says you can skip from Controller to Entity if logically appropriate. Robert Martin suggests being strict first.

Q: Is this only for Java?

No. It applies to TypeScript, Python, C#, and even Frontend (React). In React, Components are the UI layer, Hooks/Context are Use Cases, and API calls are Interface Adapters.

9. Conclusion

Clean Architecture is not a silver bullet.

It requires creating more files (Interfaces, DTOs, Mappers) and can feel like "Over-engineering" for simple CRUD apps.

However, for complex, long-lived enterprise applications, this separation of concerns is the only way to prevent the codebase from turning into a Big Ball of Mud.

It keeps your options open. It allows you to defer decisions (like "Which DB do we use?") until the last possible moment.

It keeps your core logic protected from the chaos of the outside world.