Stop Using Boolean Flags for State: Master Discriminated Unions in TypeScript

Managing API state with `isLoading`, `isError`, `data`? Learn how Discriminated Unions prevent 'impossible states' and simplify your logic.

Managing API state with `isLoading`, `isError`, `data`? Learn how Discriminated Unions prevent 'impossible states' and simplify your logic.

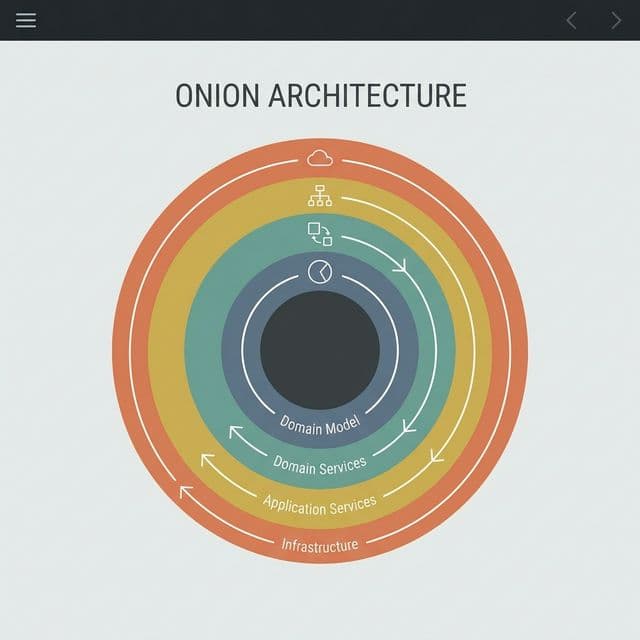

A deep dive into Robert C. Martin's Clean Architecture. Learn how to decouple your business logic from frameworks, databases, and UI using Entities, Use Cases, and the Dependency Rule. Includes Screaming Architecture and Testing strategies.

Why did Facebook ditch REST API? The charm of picking only what you want with GraphQL, and its fatal flaws (Caching, N+1 Problem).

Backend: 'Done.' Frontend: 'How to use?'. Automate this conversation with Swagger.

Put everything in one `UserContext`? Bad move. Learn how a single update re-renders the entire app and how to optimize using Context Splitting and Selectors.

isLoading is true AND isError is true?"I used individual useState for API state.

const [isLoading, setIsLoading] = useState(false);

const [isError, setIsError] = useState(false);

It looked simple. But complex logic led to bugs.

Suddenly, I had isLoading: true and isError: true simultaneously.

The UI showed a Spinner AND an Error Message. A monster UI was born.

"Loading excludes Error! Why are they independent?"

I thought "Splitting state is modular." But independent variables mean Combinatorial Explosion.

isLoading (T/F)isError (T/F)Possible combinations: 4. Valid combinations: 2. My code allowed 2 "Impossible States" to exist.

I viewed it as a "Traffic Light."

State should be like a traffic light. Mutually Exclusive.

Using TypeScript's Discriminated Unions solves this perfectly.

The key is a common field (discriminant), usually status or type.

type ApiState<T> =

| { status: 'idle' }

| { status: 'loading' }

| { status: 'success'; data: T } // data exists ONLY here

| { status: 'error'; error: string }; // error exists ONLY here

Now, getting data when status === 'loading' is a compile error.

You cannot write code that accesses invalid data.

const [state, setState] = useState<ApiState<User>>({ status: 'idle' });

// Loading

setState({ status: 'loading' });

// Success (No need to manually reset isError=false. It's a full replacement)

setState({ status: 'success', data: fetchedUser });

switch (state.status) {

case 'loading': return <Spinner />;

case 'error': return <Error msg={state.error} />;

case 'success': return <User user={state.data} />;

}

Clean logic. No if (!loading && !error && data).

TS ensures you handle all cases (Exhaustiveness Checking).

This pairs beautifully with useReducer or Redux.

type Action =

| { type: 'FETCH_START' }

| { type: 'FETCH_SUCCESS'; payload: User };

function reducer(state, action) {

if (action.type === 'FETCH_SUCCESS') {

return { status: 'success', data: action.payload };

}

}

State transitions become explicit and type-safe.

TanStack Query uses this pattern.

const { status, data } = useQuery(...)

if (status === 'success') {

// data is guaranteed defined

}

Good libraries "Make Impossible States Impossible."

What happens if you forget case 'error': in your switch statement?

TypeScript usually stays silent.

But we want it to scream "Handle every case OR ELSE!"

Enter the assertNever helper pattern using the never type.

function assertNever(x: never): never {

throw new Error("Unexpected object: " + x);

}

// ...

switch (state.status) {

case 'idle': return ...;

case 'loading': return ...;

case 'success': return ...;

// Oops, forgot 'error'

default:

// RED SQUIGGLY LINE HERE!

// "Argument of type 'ApiState<User>' is not assignable to parameter of type 'never'."

return assertNever(state);

}

Reaching default means there's a leftover type in state (the 'error' state).

assertNever only accepts never (impossible values).

Since state is not never, TS throws a compile error.

With this, if you later add status: 'refetching', the compiler essentially hunts down every switch statement in your app and yells, "Update logic here!"

It's Refactoring Nirvana.

For simple fetch, it's nice. For Payments, it's a lifesaver.

E-commerce payment page. States are wild:

Managing this with isValidating, isProcessing, isWaiting3DS booleans?

You end up with "Validating (True) AND Waiting3DS (True)" — a logical impossibility.

type PaymentState =

| { status: 'idle' }

| { status: 'validating'; couponId?: string }

| { status: 'processing'; orderId: string }

| { status: 'waiting_3ds'; redirectUrl: string; transactionId: string } // URL needed ONLY here!

| { status: 'success'; receiptUrl: string }

| { status: 'fail'; reason: string; canRetry: boolean };

Each state carries completely different data.

redirectUrl exists ONLY in waiting_3ds.

Without unions, redirectUrl would be string | undefined everywhere. "Does this exist in validation phase?" Who knows.

With unions, the UI code is crystal clear:

if (state.status === 'waiting_3ds') {

// TS guarantees state.redirectUrl exists!

window.location.href = state.redirectUrl;

}

Q: Must the field be named status?

A: No. type, kind, tag works too. Just pick a convention. type is common in Redux, status in React Query.

Q: Is it overkill for just 2 states (Success/Fail)?

A: If it's a simple toggle (Open/Close), use isOpen boolean. But if Data is attached (Success has Data, Fail has Error), use Unions. It guarantees safety.

Q: Can't I keep isLoading separate for refetching?

A: For "Refetching while showing old data," you might be tempted to keep isLoading. A better way is to add isRefetching property inside the success state, or define a reloading state that carries oldData. The goal is to make the state Explicit.

status field. Let the compiler block logical errors.

Another classic example where Discriminated Unions shine is Form Validation. Often, we see code like this:

type FormState = {

isValid: boolean;

isSubmitting: boolean;

errors: Record<string, string>;

};

This attempts to model everything with loose fields. But consider this:

isValid: true but have errors?isSubmitting: true but isValid: false?A better approach is to model the lifecycle of the form:

type FormState =

| { status: 'idle'; values: FormData }

| { status: 'validating'; values: FormData }

| { status: 'submitting'; values: FormData }

| { status: 'success' }

| { status: 'error'; errors: Record<string, string>; values: FormData };

By doing this, you prevent the UI from trying to submit a form that is currently in the error state. The submit button can be disabled effectively because the submitting state is mutually exclusive from error or idle.

Switching from "Boolean Soup" to Discriminated Unions is a paradigm shift.

At first, it feels like more typing. defining type ApiState = ... takes more lines than useState(false).

However, the Debt of boolean flags accumulates over time.

Discriminated Unions pay off this debt upfront. They make your state "Correct by Construction." If it compiles, it likely handles all states correctly.

So next time you reach for setIsLoading(true), stop and ask:

"Is this loading state exclusive to other states?"

If yes, use a Union.