GraphQL vs REST: Buffet or Set Menu?

Why did Facebook ditch REST API? The charm of picking only what you want with GraphQL, and its fatal flaws (Caching, N+1 Problem).

Why did Facebook ditch REST API? The charm of picking only what you want with GraphQL, and its fatal flaws (Caching, N+1 Problem).

Why does my server crash? OS's desperate struggle to manage limited memory. War against Fragmentation.

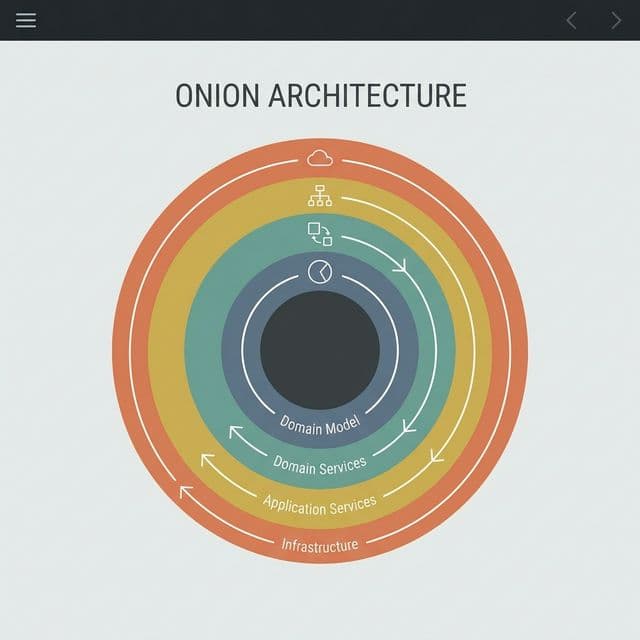

A deep dive into Robert C. Martin's Clean Architecture. Learn how to decouple your business logic from frameworks, databases, and UI using Entities, Use Cases, and the Dependency Rule. Includes Screaming Architecture and Testing strategies.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

A comprehensive deep dive into client-side storage. From Cookies to IndexedDB and the Cache API. We explore security best practices for JWT storage (XSS vs CSRF), performance implications of synchronous APIs, and how to build offline-first applications using Service Workers.

I was genuinely frustrated the day I built an admin dashboard at my startup. To render one single screen, I had to call REST APIs five times.

// Loading one dashboard...

const user = await fetch('/api/users/me'); // 1st call

const stats = await fetch('/api/stats/summary'); // 2nd call

const recentPosts = await fetch('/api/posts?limit=5'); // 3rd call

const notifications = await fetch('/api/notifications'); // 4th call

const team = await fetch('/api/teams/1'); // 5th call

Opening the Network tab showed five requests cascading like a waterfall. Each needed its own loading spinner. The structure required getting userId from the first API before calling the second. Is this really how we develop in 2024?

The funnier part: half the data returned by GET /api/users/me was unused. Fields like address, phoneNumber, createdAt came in the JSON, but all I needed were name and avatar. In mobile environments, wasting data like this drains users' data plans.

"Can't we merge these APIs into one? Can't I request only the fields I need?"

The answer was GraphQL. Understanding this technology made it crystal clear why Facebook had to invent it in 2012.

The easiest way to understand GraphQL is through a restaurant metaphor. This mental model clicked perfectly when I first grasped the concept.

REST API is a 'Set Menu Restaurant'. You must order exactly what's on the menu. You get the entire set decided by the chef (Backend Developer).

GET /users/1): You receive Kimbap + Ramen + Pork Cutlet.GET /users/1, GET /posts)GraphQL is a 'Hotel Buffet'. You grab a plate (Query) and pick only what you want. The chef sets up the buffet table (Schema), and guests (Clients) compose their own plates.

After hearing this metaphor, GraphQL's core philosophy condensed into one sentence:

"Client-Driven Data Fetching"

REST follows "Here's what I'll give you" from the server, while GraphQL follows "Give me this" from the client. The power dynamic completely flips.

Facebook's motivation for creating GraphQL was mobile apps. In 2012, smartphone screens were small and networks were slow. REST APIs had these problems:

// GET /api/users/1

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Ratia",

"email": "ratia@example.com",

"phoneNumber": "010-1234-5678",

"address": "Seoul, Korea",

"createdAt": "2025-01-01T00:00:00Z",

"updatedAt": "2025-05-16T10:30:00Z",

"preferences": {

"theme": "dark",

"language": "ko",

"notifications": true

},

"billing": {

"plan": "premium",

"nextPayment": "2025-06-01"

}

}

The screen only displays name, but this massive JSON flies over the wire. Repeating this on mobile 3G creates the worst user experience.

Consider an SNS feed. To display one post:

GET /posts/123 - Post infoGET /users/456 - Author infoGET /posts/123/comments - Comment listGET /posts/123/likes - Like countFour API calls needed. This is called a "Waterfall Request". You must receive the first response before sending the second request.

One hundred screens require one hundred endpoints. When the mobile team says "We want to show createdAt here too," Backend developers must create new endpoints or modify existing APIs. The cycle of Frontend change → Backend deployment → Re-testing repeats endlessly.

I understood this structure was inefficient. Now let me properly break down how GraphQL solves these problems.

GraphQL runs on a type system. Every data shape is pre-defined in .graphql files. This is the buffet table (Menu).

# schema.graphql

type User {

id: ID! # ! = Non-Nullable (required)

name: String!

email: String!

avatar: String

posts: [Post!]! # Post array (empty allowed, null not allowed)

createdAt: DateTime! # Custom Scalar

}

type Post {

id: ID!

title: String!

content: String!

author: User! # Relation

comments: [Comment!]!

likes: Int!

publishedAt: DateTime

}

type Comment {

id: ID!

text: String!

author: User!

}

# Custom Scalar definition (Date/Time)

scalar DateTime

# Root Query (Entry Point)

type Query {

user(id: ID!): User

post(id: ID!): Post

posts(limit: Int, offset: Int): [Post!]!

me: User # Currently logged-in user

}

# Root Mutation (Data modification)

type Mutation {

createPost(title: String!, content: String!): Post!

deletePost(id: ID!): Boolean!

likePost(id: ID!): Post!

}

# Root Subscription (Real-time subscription)

type Subscription {

postAdded: Post!

commentAdded(postId: ID!): Comment!

}

This Schema shows what dishes are on the buffet table at a glance. User has name, email, avatar, and connects to Post through the posts field. Like SQL's ERD (Entity Relationship Diagram), it directly expresses the graph structure of data.

Beyond basic types (String, Int, Boolean, ID), you can create custom types.

// Custom Scalar implementation (JavaScript)

const { GraphQLScalarType } = require('graphql');

const DateTime = new GraphQLScalarType({

name: 'DateTime',

description: 'ISO-8601 formatted date/time',

serialize(value) {

return value.toISOString(); // DB → Client

},

parseValue(value) {

return new Date(value); // Client → DB

},

});

This automatically converts strings like "2025-05-17T10:30:00Z" into Date objects.

All GraphQL operations fall into three types.

# User info + recent 3 posts

query GetUserWithPosts {

user(id: "1") {

name

avatar

posts(limit: 3) {

id

title

likes

publishedAt

}

}

}

# Response

{

"data": {

"user": {

"name": "Ratia",

"avatar": "/avatars/ratia.jpg",

"posts": [

{

"id": "101",

"title": "Learning GraphQL",

"likes": 42,

"publishedAt": "2025-05-16T10:00:00Z"

},

{

"id": "102",

"title": "Solving N+1 Problem",

"likes": 38,

"publishedAt": "2025-05-15T14:30:00Z"

},

{

"id": "103",

"title": "Apollo Client Setup",

"likes": 29,

"publishedAt": "2025-05-14T09:20:00Z"

}

]

}

}

}

With REST: Two calls - GET /users/1, GET /users/1/posts?limit=3.

With GraphQL: Solved in one go.

# Creating a post

mutation CreatePost {

createPost(

title: "GraphQL is a Buffet"

content: "REST is a set menu, GraphQL is a hotel buffet..."

) {

id

title

author {

name

}

publishedAt

}

}

# Response

{

"data": {

"createPost": {

"id": "104",

"title": "GraphQL is a Buffet",

"author": {

"name": "Ratia"

},

"publishedAt": "2025-05-17T11:00:00Z"

}

}

}

Key point: You immediately receive the created data in exactly the shape you want. With REST, you often need to call GET /posts/104 again after POST /posts.

# Real-time new comment reception (WebSocket)

subscription OnCommentAdded {

commentAdded(postId: "101") {

id

text

author {

name

avatar

}

}

}

# Automatically pushed when someone comments

{

"data": {

"commentAdded": {

"id": "501",

"text": "Thanks for the great article!",

"author": {

"name": "Kim Developer",

"avatar": "/avatars/kim.jpg"

}

}

}

}

Used for real-time chat, notifications, stock prices. With REST, you'd need Long Polling or Server-Sent Events separately, but GraphQL has Subscription as a standard spec.

Schema is the "menu," Query is the "order form." Then who actually makes the food (data)? The Resolver.

// resolver.js

const resolvers = {

Query: {

// user(id: ID!): User

user: async (parent, args, context, info) => {

const { id } = args;

// Query user from DB

return await context.db.user.findUnique({ where: { id } });

},

// me: User

me: async (parent, args, context) => {

const userId = context.currentUser.id; // Extract from JWT token

return await context.db.user.findUnique({ where: { id: userId } });

},

},

Mutation: {

// createPost(title: String!, content: String!): Post!

createPost: async (parent, args, context) => {

const { title, content } = args;

const authorId = context.currentUser.id;

return await context.db.post.create({

data: { title, content, authorId },

});

},

},

// Field Resolver (resolving nested fields)

User: {

// When User.posts field is requested

posts: async (parent, args, context) => {

// parent = current User object

return await context.db.post.findMany({

where: { authorId: parent.id },

take: args.limit,

});

},

},

Post: {

// When Post.author field is requested

author: async (parent, context) => {

return await context.db.user.findUnique({

where: { id: parent.authorId },

});

},

},

};

id, limit, etc.)Here's what it comes down to: GraphQL is an engine that recursively executes Resolvers based on the Query. When a Query like user(id: 1) { name, posts { title } } comes in:

Query.user Resolver → Returns User objectUser.posts Resolver → Returns Post arraytitle field from each PostThis process proceeds like traversing a tree. That's why it's called Graph QL.

If you naively write Resolvers, a performance disaster occurs. This is GraphQL's biggest weakness.

# 10 users and each user's post titles

query {

users(limit: 10) {

name

posts {

title

}

}

}

Naive Resolver:

const resolvers = {

Query: {

users: async () => {

return await db.user.findMany({ take: 10 }); // 1 query

},

},

User: {

posts: async (parent) => {

// Executed for EACH User!

return await db.post.findMany({ where: { authorId: parent.id } }); // 10 queries

},

},

};

Result: 1 + 10 = 11 DB queries

If 100 users? 101 queries. 1000 users? 1001 queries.

This is the N+1 Problem. One query to fetch the list + N additional queries for each item.

Facebook's DataLoader library solves this through Batching + Caching.

// dataloader.js

const DataLoader = require('dataloader');

// Batch Function: Query multiple IDs at once

const batchUsers = async (userIds) => {

// [1, 2, 3] -> SELECT * FROM users WHERE id IN (1, 2, 3)

const users = await db.user.findMany({

where: { id: { in: userIds } },

});

// Return sorted by ID order (important!)

return userIds.map(id => users.find(user => user.id === id));

};

const userLoader = new DataLoader(batchUsers);

// Usage

const user1 = await userLoader.load(1);

const user2 = await userLoader.load(2);

const user3 = await userLoader.load(3);

// Actually merged into 1 query: SELECT * WHERE id IN (1,2,3)

Applied to Resolver:

const resolvers = {

Post: {

author: async (parent, args, context) => {

// Called N times, but DataLoader automatically batches

return await context.loaders.user.load(parent.authorId);

},

},

};

// Inject Loader into Context

const server = new ApolloServer({

typeDefs,

resolvers,

context: () => ({

db,

loaders: {

user: new DataLoader(batchUsers),

post: new DataLoader(batchPosts),

},

}),

});

Before: 101 queries After: 2 queries (Users once + Posts once, using IN clause)

When I first understood DataLoader, I thought "This is real magic." It automatically collects requests accumulated during one Event Loop tick and executes them together. Developers just call the load(id) function.

# Fragment definition

fragment UserInfo on User {

id

name

avatar

createdAt

}

# Reuse in multiple places

query {

me {

...UserInfo

posts {

author {

...UserInfo

}

}

}

}

Reduces code duplication and expresses component-level data requirements like "always show these fields on this screen."

# Variable declaration ($userId = variable name, ID! = type)

query GetUser($userId: ID!, $postLimit: Int = 5) {

user(id: $userId) {

name

posts(limit: $postLimit) {

title

}

}

}

# Passed separately

{

"userId": "123",

"postLimit": 10

}

Instead of dynamically assembling query strings, separating into variables is better for security (SQL Injection prevention) and caching.

query GetUser($userId: ID!, $withPosts: Boolean!) {

user(id: $userId) {

name

posts @include(if: $withPosts) {

title

}

}

}

# Only request posts field when withPosts = true

@include(if: Boolean): Include only if condition is true@skip(if: Boolean): Exclude if condition is trueRequest only necessary data based on screen state.

Let's connect Apollo Client, the most widely used client library, to React.

// apolloClient.js

import { ApolloClient, InMemoryCache, HttpLink } from '@apollo/client';

const client = new ApolloClient({

link: new HttpLink({ uri: 'https://api.example.com/graphql' }),

cache: new InMemoryCache(),

});

export default client;

// index.js

import { ApolloProvider } from '@apollo/client';

import client from './apolloClient';

ReactDOM.render(

<ApolloProvider client={client}>

<App />

</ApolloProvider>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

// UserProfile.jsx

import { useQuery, gql } from '@apollo/client';

const GET_USER = gql`

query GetUser($userId: ID!) {

user(id: $userId) {

id

name

avatar

posts(limit: 5) {

id

title

likes

}

}

}

`;

function UserProfile({ userId }) {

const { loading, error, data } = useQuery(GET_USER, {

variables: { userId },

});

if (loading) return <Spinner />;

if (error) return <p>Error: {error.message}</p>;

const { user } = data;

return (

<div>

<img src={user.avatar} alt={user.name} />

<h1>{user.name}</h1>

<ul>

{user.posts.map(post => (

<li key={post.id}>

{post.title} ({post.likes} likes)

</li>

))}

</ul>

</div>

);

}

With REST: Multiple fetch calls inside useEffect, managing each with useState.

With Apollo Client: One line useQuery does it all. Loading/Error states auto-managed.

import { useMutation, gql } from '@apollo/client';

const LIKE_POST = gql`

mutation LikePost($postId: ID!) {

likePost(id: $postId) {

id

likes

}

}

`;

function LikeButton({ postId }) {

const [likePost, { loading }] = useMutation(LIKE_POST, {

variables: { postId },

// Optimistic UI: Update UI before response

optimisticResponse: {

likePost: {

id: postId,

likes: (prev) => prev + 1,

},

},

// Cache update

update(cache, { data: { likePost } }) {

cache.modify({

id: cache.identify({ __typename: 'Post', id: postId }),

fields: {

likes() {

return likePost.likes;

},

},

});

},

});

return (

<button onClick={likePost} disabled={loading}>

{loading ? '...' : 'Like'}

</button>

);

}

Optimistic UI: Update UI first without waiting for server response to increase perceived speed. Rollback on failure.

Apollo Client's real strength is Normalized Cache. Even if the same object appears in multiple Queries, it's stored in one place.

// Cache structure (internally normalized like this)

{

"User:1": {

"__typename": "User",

"id": "1",

"name": "Ratia",

"avatar": "/avatars/ratia.jpg"

},

"Post:101": {

"__typename": "Post",

"id": "101",

"title": "Learning GraphQL",

"likes": 42,

"author": { "__ref": "User:1" } // Reference

},

"ROOT_QUERY": {

"user({\"id\":\"1\"})": { "__ref": "User:1" },

"post({\"id\":\"101\"})": { "__ref": "Post:101" }

}

}

Even if User:1 appears in multiple Queries, it's managed as one object. When a likePost Mutation modifies Post:101.likes, all components referencing this Post automatically re-render.

const client = new ApolloClient({

cache: new InMemoryCache({

typePolicies: {

Query: {

fields: {

posts: {

// Pagination: Append to existing list

keyArgs: false,

merge(existing = [], incoming) {

return [...existing, ...incoming];

},

},

},

},

},

}),

});

Cache-First: No network request if in cache (default) Network-Only: Always fetch fresh from server Cache-and-Network: Show cache first, fetch new data in background and update

Now let me clearly organize when to use what.

| Scenario | Recommendation | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Dashboard, Admin Panel | GraphQL | Must fetch complex relational data at once |

| Mobile App | GraphQL | Data saving essential, prevent over-fetching |

| Public API (GitHub, Twitter) | REST | Standard HTTP caching, easy documentation, low barrier |

| Simple CRUD (Blog, Forum) | REST | GraphQL is over-engineering without complex relations |

| Real-time Features (Chat, Notifications) | GraphQL | Standard Subscription support |

| File Upload Heavy | REST | multipart/form-data is standard, GraphQL is complex |

| Microservice Communication | REST / gRPC | Internal APIs don't need GraphQL flexibility |

| Legacy System Integration | REST | Compatibility with existing infrastructure |

GraphQL's flexibility is also vulnerable to malicious attacks.

# Infinite nested query to crash server

query EvilQuery {

user(id: "1") {

posts {

author {

posts {

author {

posts {

author {

posts {

# ... 100 levels deep

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

const depthLimit = require('graphql-depth-limit');

const server = new ApolloServer({

typeDefs,

resolvers,

validationRules: [depthLimit(5)], // Max 5 levels allowed

});

const { createComplexityLimitRule } = require('graphql-validation-complexity');

// Assign cost to each field

const complexityRule = createComplexityLimitRule(1000, {

scalarCost: 1,

objectCost: 5,

listFactor: 10,

});

const server = new ApolloServer({

validationRules: [complexityRule],

});

Nesting lists like posts(limit: 100) { comments { author } } calculates a cost of 100 * 10 * 5 = 5000, and exceeding the limit gets rejected.

// Limit to 100 requests per minute per IP

const rateLimit = require('express-rate-limit');

app.use('/graphql', rateLimit({

windowMs: 60 * 1000, // 1 minute

max: 100,

}));

REST easily limits by URL, but GraphQL has all requests to /graphql, so you must analyze per Query.

Six months after adopting GraphQL in production, I now clearly understand when it shines and when it's poison.

"GraphQL is technology that moves complexity from Backend to Frontend."

REST has Backend deciding everything. "This endpoint gives this data." Clear but inflexible.

GraphQL has Frontend deciding. "I need this data." Flexible but Backend becomes proportionally more complex. You must care about DataLoader, Query Complexity, Caching all at once.

For startups, starting with REST to build fast, then switching to GraphQL as complexity grows is realistic. Choosing GraphQL from the start means spending too much time on the learning curve.

But once you properly understand GraphQL, going back to REST becomes hard. Once you taste the freedom of the buffet, the set menu restaurant feels suffocating.