Bloom Filter: '없다는 건 확실해, 있다는 건... 글쎄?' (확률적 자료구조)

엄청난 데이터를 아주 적은 메모리로 검사하는 방법. 100% 정확도를 포기하고 99.9%의 효율을 얻는 확률적 자료구조의 세계. 비트코인 지갑과 스팸 필터는 왜 이것을 쓸까요?

엄청난 데이터를 아주 적은 메모리로 검사하는 방법. 100% 정확도를 포기하고 99.9%의 효율을 얻는 확률적 자료구조의 세계. 비트코인 지갑과 스팸 필터는 왜 이것을 쓸까요?

미로를 탈출하는 두 가지 방법. 넓게 퍼져나갈 것인가(BFS), 한 우물만 팔 것인가(DFS). 최단 경로는 누가 찾을까?

이름부터 빠릅니다. 피벗(Pivot)을 기준으로 나누고 또 나누는 분할 정복 알고리즘. 왜 최악엔 느린데도 가장 많이 쓰일까요?

매번 3-Way Handshake 하느라 지쳤나요? 한 번 맺은 인연(TCP 연결)을 소중히 유지하는 법. HTTP 최적화의 기본.

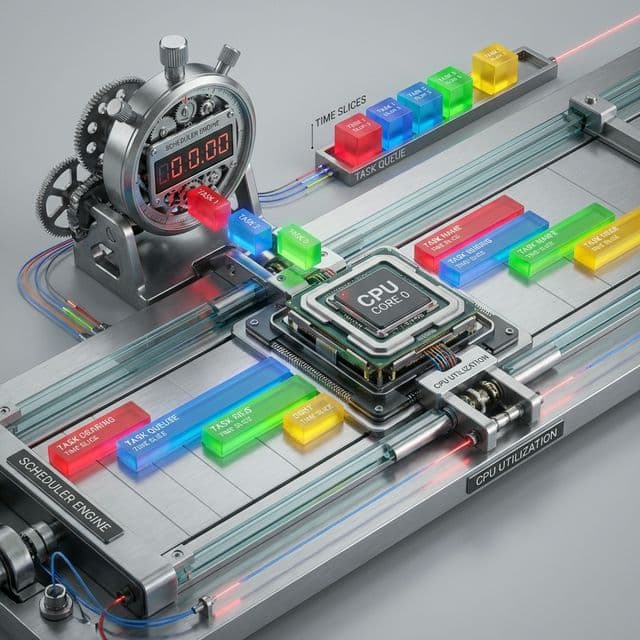

CPU는 하나인데 프로그램은 수십 개 실행됩니다. 운영체제가 0.01초 단위로 프로세스를 교체하며 '동시 실행'의 환상을 만드는 마술. 선점형 vs 비선점형, 기아 현상(Starvation), 그리고 현대적 해법인 MLFQ를 파헤칩니다.

대규모 데이터에서 존재 여부를 빠르게 확인해야 할 때 문제가 생긴다.

수억 개 이상의 아이디가 있는 사이트에서 new_user라는 아이디가 이미 있는지 확인하려면?

이때 100MB 정도의 메모리만 쓰면서 아주 빠르게 검사할 방법이 없을까요? 단, "중복이 아닌데 중복이라고 할 수도 있음(False Positive)"을 감수한다면요. 이것이 블룸 필터(Bloom Filter)입니다. 처음 이 개념을 접했을 때 "오차가 있는데 왜 쓰지?"라고 의아했는데, 실제 사례들을 보면서 "결국 이거였다"는 걸 이해했습니다. 트레이드오프의 진수죠.

블룸 필터는 거대한 비트 배열(Bit Array, 000...000)과 여러 개의 해시 함수로 구성됩니다.

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0"apple" 삽입.h1("apple") % 10 = 2h2("apple") % 10 = 5h3("apple") % 10 = 71로 세팅. -> 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 "banana" 있나?

0이네?"apple" 있나?

1이네?이 메커니즘을 직접 구현해보면서 비트 배열의 위력을 정말 받아들였습니다. 숫자 대신 비트로 관리하는 것만으로 메모리가 수십 배 절약되는 게 체감되더군요.

"있을 수도 있고 없을 수도 있습니다." 하지만 "없다"는 말은 100% 진실입니다.

이 특성 때문에 블룸 필터는 "비싼 연산(DB 조회)을 하기 전에, 확실히 없는 놈을 1차로 걸러내는 용도"로 씁니다. 실제로 Cache Penetration 공격을 막을 때 이게 얼마나 와닿았는지 모릅니다. DB가 터지는 걸 비트 몇 개로 막아버리니까요.

SSTable 파일에 찾으려는 데이터가 있는지 확인할 때 사용.import mmh3 # MurmurHash (빠른 해시 함수)

from bitarray import bitarray

class BloomFilter:

def __init__(self, size, hash_count):

self.size = size

self.hash_count = hash_count

self.bit_array = bitarray(size)

self.bit_array.setall(0)

def add(self, string):

for seed in range(self.hash_count):

result = mmh3.hash(string, seed) % self.size

self.bit_array[result] = 1

def lookup(self, string):

for seed in range(self.hash_count):

result = mmh3.hash(string, seed) % self.size

if self.bit_array[result] == 0:

return "Definitely No"

return "Maybe Yes"

# 사용

bf = BloomFilter(500000, 7)

bf.add("hello")

print(bf.lookup("hello")) # Maybe Yes

print(bf.lookup("world")) # Definitely No

블룸 필터의 성능은 비트 배열 크기($m$), 해시 함수 개수($k$), 데이터 개수($n$)에 달려 있습니다. False Positive 확률($p$)을 구하는 공식은 다음과 같습니다 (오일러 상수 $e$ 등장). $$ p \approx (1 - e^)^k $$

이 수식이 주는 교훈은 무엇일까요?

오리지널 블룸 필터는 치명적인 단점이 있습니다. "삭제(Deletion)"가 불가능하다는 점입니다. 비트를 0으로 끄는 순간, 그 비트를 공유하던 다른 죄 없는 데이터들도 "없음"으로 처리되기 때문입니다.

비트(0/1) 대신 작은 카운터(3~4비트 정수)를 씁니다.

+1-1

이제 삭제가 가능해졌습니다! 하지만 메모리 사용량이 3~4배($m$) 늘어납니다. 세상에 공짜는 없으니까요.최근에는 블룸 필터보다 Cuckoo Filter가 대세입니다.

RedisBloom도 Cuckoo Filter를 지원합니다.블룸 필터는 처음에 사이즈($m$)를 정해야 합니다. 만약 예상보다 데이터($n$)가 10배 더 들어오면 오차율이 폭증합니다. 그렇다고 무작정 크게 잡으면 낭비죠. Scalable Bloom Filter는 필터가 가득 차면, 2배 더 큰 새로운 필터를 하나 더 만듭니다.

비트 배열이 너무 희소(Sparse)하다면, 0이 너무 많아서 낭비일 수 있습니다. (예: 1GB 배열에 1비트만 1이라면?). 이때는 Golomb-Rice Coding 같은 기법으로 비트맵 자체를 압축해서 저장할 수도 있습니다. 하지만 압축을 풀면서 조회해야 하므로 CPU를 더 씁니다. (Time-Space Tradeoff).

블룸 필터가 얼마나 가벼운지 비교해봤다. (데이터 1000만 개 기준)

| 자료구조 | 시간 복잡도 (탐색) | 공간 복잡도 | 메모리 사용량 (예상) | 정확도 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HashSet | $O(1)$ | $O(N)$ | 약 640MB | 100% |

| BST (Red-Black) | $O(\log N)$ | $O(N)$ | 약 480MB | 100% |

| Bloom Filter | $O(K)$ | $O(M)$ | 약 12MB | 99% (확률적) |

보시다시피 메모리 차이가 수십 배입니다. 메모리 차이가 수십 배라면, 정확도 1%를 포기하고 서버 비용을 대폭 절감할 수 있다는 사례들이 있다. 이것이 바로 Engineering Trade-off의 핵심입니다. 블룸 필터는 이 트레이드오프의 가장 우아한 예시입니다.

"개발할 때 비트 배열 크기($m$)를 얼마로 잡아야 하죠?" 계산공식이 복잡하다면, 이 경험적 수치(Rule of Thumb)를 기억하세요.

결론: 그냥 넉넉하게 데이터 개수 $\times$ 20비트 잡으세요. 그래도 해시맵보다 100배 작습니다.

Counting Bloom Filter나 Cuckoo Filter를 써야 합니다.BF.ADD key item, BF.EXISTS key item 명령어를 사용합니다. (RedisBloom 모듈 설치 필요). 만약 BF.EXISTS가 0을 반환하면 DB를 조회할 필요가 전혀 없으므로 부하를 크게 줄일 수 있습니다.현업에서 블룸 필터를 가장 쉽게 쓰는 방법은 Redis입니다.

Redis Stack에는 RedisBloom 모듈이 포함되어 있습니다. 직접 비트 배열을 관리할 필요가 없죠.

# 초기화 - 에러율 0.1%, 아이템 1000개 예상

BF.RESERVE myFilter 0.001 1000

# 추가

BF.ADD myFilter "user1"

# (integer) 1 (처음 들어옴)

# 확인

BF.EXISTS myFilter "user1"

# (integer) 1 (아마도 있음)

BF.EXISTS myFilter "user999"

# (integer) 0 (확실히 없음 -> DB 조회 Skip!)

악의적인 해커가 "절대 없는 키" (예: user_id=-999)로 초당 100만 번 요청을 보냅니다.

이걸 Cache Penetration이라고 합니다. 이때 블룸 필터를 캐시 앞단에 둡니다. "이 키는 우리 데이터베이스에 절대 없어!"라고 0.01초 만에 쳐내버립니다. DB는 평화를 되찾습니다. 이것이 블룸 필터의 존재 이유입니다.

블룸 필터가 마음에 들었다면, 이 친구들도 반드시 알아야 합니다. 빅데이터의 세계에서는 "정확도"를 조금 팔아서 "엄청난 속도와 메모리 절약"을 사는 거래가 성립하기 때문입니다.

"우리 사이트의 고유 방문자 수(UV)가 몇 명이지?" 10억 개의 IP 주소를 다 Set에 저장하면 메모리가 터집니다. HyperLogLog는 해시값의 이진 표현에서 "앞부분에 0이 연속으로 몇 개 나오는지(Leading Zeros)"를 관찰하여 전체 개수를 추정합니다.

PFADD, PFCOUNT가 바로 이것입니다."지난 1시간 동안 가장 많이 검색된 단어 TOP 10은?" 블룸 필터가 "있냐/없냐"만 따진다면, Count-Min Sketch는 "몇 번 나왔냐"를 셉니다. 여러 개의 해시 함수를 돌려 2차원 배열의 카운터를 증가시킵니다. 당연히 충돌(Collision) 때문에 실제보다 더 많이 셌을 수도 있지만(Over-estimation), 절대 적게 세지는 않습니다. 최소값(Min)을 취해 오차를 보정하기 때문에 이름이 Count-Min입니다.

"이 문서랑 저 문서랑 내용이 90% 이상 똑같네? 표절인가?" 일반적인 해시(MD5, SHA-256)는 글자 하나만 달라도 결과가 완전히 달라집니다(Avalanche Effect). 하지만 SimHash는 비슷한 문서는 비슷한 해시값을 가지도록 설계되었습니다(Locality Sensitive Hashing - LSH).

엄밀히 말해 확률적 자료구조는 아니지만, 해시를 이용한 분산 시스템의 꽃입니다.

캐시 서버가 10대에서 11대로 늘어날 때, key % 10 공식을 쓰면 모든 데이터가 뒤섞여버립니다(Reshuffling).

Consistent Hashing은 해시 공간을 원형(Ring)으로 배치하여, 서버가 추가/삭제되어도 인접한 일부 데이터만 이동하도록 만듭니다.

아마존 다이아나모(Dynamo)나 카산드라(Cassandra)가 이 방식을 씁니다.

블룸 필터는 우리에게 중요한 교훈을 줍니다. "때로는 100%의 정확도보다 효율성이 중요하다." 99.9%의 정확도만으로도 비용을 1/1000로 줄일 수 있다면? 그건 타협이 아니라 혁신입니다. 세상 모든 것을 저장하고 기억하려 하지 마세요. 가끔은 "아마도 맞을 거야"라는 유연함이 시스템 전체를 살립니다. 이 철학이 정말 와닿았고, 실제로 리소스 최적화를 고민할 때마다 블룸 필터의 교훈을 떠올립니다.

At large scale, checking whether an item already exists becomes expensive fast. Consider a user signup system where you need to check if a username already exists among hundreds of millions of records. Every naive solution has a serious cost:

Is there a way to check membership using around 100MB of memory instead of 20GB? Yes—if you're willing to accept a small chance of being wrong.

That's the core idea behind Bloom Filters. The concept seems absurd at first. A data structure that admits it can be wrong? Who would use that? Turns out, basically everyone dealing with massive datasets.

Here's what blew my mind. A Bloom Filter never gives false negatives. If it says "this item is NOT in the set," that's 100% true. But if it says "this item IS in the set," there's a small chance it's lying. It might be a false positive caused by hash collisions.

Let me break down how this black magic works.

Imagine a giant array of bits (not bytes, bits). Let's start with a tiny example: a 10-bit array initialized to all zeros.

[0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]

When you insert the string "apple", you run it through multiple hash functions. Let's say you use 3 different hash functions:

h1("apple") % 10 = 2

h2("apple") % 10 = 5

h3("apple") % 10 = 7

You flip bits at positions 2, 5, and 7 to 1:

[0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0]

Now let's check if "banana" exists:

h1("banana") % 10 = 2

h2("banana") % 10 = 5

h3("banana") % 10 = 9

You check positions 2, 5, and 9. Position 9 is still 0!

Conclusion: "banana" was definitely never added. If it had been added, position 9 would be 1.

Let's verify "apple" again:

Positions: 2, 5, 7

Values: [1, 1, 1]

All bits are set. Conclusion: "apple" is probably in the set. But here's the catch: what if some other strings happened to set bits 2, 5, and 7? You can't be 100% sure.

This asymmetry is beautiful. The Bloom Filter is conservative about negatives (never lies about absence) but optimistic about positives (might hallucinate presence). For many applications, that's exactly what you want.

When I first saw this, I thought: "This is useless. If it can lie, what's the point?"

Then I learned about the use cases. And everything clicked.

Chrome maintains a list of millions of malicious URLs. Checking every URL you visit against a remote server would be slow and privacy-invasive. Instead, Chrome downloads a Bloom Filter to your browser.

This reduces server load by 99.9% while catching every single malicious site (no false negatives, remember?).

Lightweight Bitcoin wallets don't download the entire blockchain (hundreds of GB). Instead, they use Bloom Filters to ask full nodes: "Do any recent blocks contain transactions involving my addresses?" The full node uses the filter to respond without learning which addresses you actually own. Privacy + efficiency.

Databases built on LSM trees (Log-Structured Merge Trees) store data in immutable files called SSTables. Before reading an SSTable from disk, they check a Bloom Filter: "Does this file even contain the key I'm looking for?"

If the filter says "No," they skip the disk read entirely. This avoids millions of unnecessary disk I/Os per second. The false positive rate (reading a file that turns out not to have your key) is a tiny price to pay.

Theory is cool, but I needed to feel this in my bones. So I built one.

import mmh3 # MurmurHash3 - fast, non-cryptographic

from bitarray import bitarray

class BloomFilter:

def __init__(self, size, hash_count):

self.size = size

self.hash_count = hash_count

self.bit_array = bitarray(size)

self.bit_array.setall(0)

def add(self, item):

for seed in range(self.hash_count):

index = mmh3.hash(item, seed) % self.size

self.bit_array[index] = 1

def check(self, item):

for seed in range(self.hash_count):

index = mmh3.hash(item, seed) % self.size

if self.bit_array[index] == 0:

return "Definitely No"

return "Maybe Yes"

# Test it

bf = BloomFilter(size=500000, hash_count=7)

bf.add("alice")

bf.add("bob")

print(bf.check("alice")) # Maybe Yes

print(bf.check("charlie")) # Definitely No

You might wonder why I didn't use SHA-256 or MD5. Cryptographic hash functions are deliberately slow to resist brute-force attacks. But Bloom Filters need to hash millions of items per second. Non-cryptographic hashes like MurmurHash, CityHash, or xxHash are 10-100x faster and have excellent distribution properties. Security doesn't matter here; speed does.

This is where it gets beautiful. The false positive rate ($p$) depends on three parameters:

The formula (derived using probability theory) is:

$$ p \approx (1 - e^)^k $$

Where $e$ is Euler's number (2.718...).

At first, I thought: "More hash functions = better, right?" Wrong. Too many hash functions fill up the bit array too quickly. Too few cause too many collisions. There's an optimal sweet spot:

$$ k_ = (m/n) \ln 2 \approx 0.693 \times (m/n) $$

If your bit array is 10x the size of your dataset ($m/n = 10$), the optimal number of hash functions is:

$$ k = 0.693 \times 10 \approx 7 $$

With 7 hash functions, your false positive rate is about 1%. That means 99 out of 100 "Maybe Yes" answers are correct. For most applications, that's phenomenal.

This was my real aha moment: engineering isn't about perfection. It's about tradeoffs. Bloom Filters teach you to give up 1% accuracy for 99% memory savings. That's not a compromise—that's genius.

For practical use, the math doesn't need to be redone from scratch every time. Here's the rule of thumb:

Compare that to a HashSet storing 1 million 20-byte strings: 20 MB. The Bloom Filter is 10-20x smaller even with generous sizing.

Let's compare memory usage for 10 million items:

| Data Structure | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | Memory Used | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HashSet | $O(1)$ | $O(N)$ | ~640 MB | 100% |

| Red-Black Tree | $O(\log N)$ | $O(N)$ | ~480 MB | 100% |

| Bloom Filter | $O(K)$ | $O(M)$ | ~12 MB | 99% |

That's a 50x memory reduction. When infrastructure costs are significant, trading 1% accuracy for a 50x memory cut is an engineering decision worth considering—cases exist where this tradeoff has led to dramatic cost savings.

Bloom Filters have one massive weakness: you can't delete items. If you flip a bit back to 0, you might accidentally "delete" other items that share that bit. It's like trying to erase one word from a palimpsest—you damage the words next to it.

Instead of storing bits (0 or 1), store small counters (e.g., 3-4 bit integers):

Now deletion works! But you've increased memory usage by 3-4x. Still better than a HashSet, but not as magical.

This is the modern alternative. Cuckoo Filters use Cuckoo Hashing (a clever collision resolution technique) to allow deletions while using even less memory than Counting Bloom Filters. They're also faster due to better cache locality. Redis's RedisBloom module supports Cuckoo Filters.

What if your dataset grows beyond your initial estimate? A fixed-size Bloom Filter's error rate explodes. A Scalable Bloom Filter solves this by chaining multiple filters:

You check all layers sequentially. This lets you handle unbounded growth at the cost of slightly slower lookups as layers accumulate.

The easiest way to use Bloom Filters in production is Redis. The RedisBloom module (part of Redis Stack) gives you ready-to-use commands:

# Reserve a filter: 0.1% error rate, 1000 expected items

BF.RESERVE users 0.001 1000

# Add a user

BF.ADD users "alice"

# (integer) 1

# Check existence

BF.EXISTS users "alice"

# (integer) 1 (probably exists)

BF.EXISTS users "eve"

# (integer) 0 (definitely doesn't exist - skip DB query!)

Here's a nightmare scenario: an attacker floods your API with requests for keys that definitely don't exist (e.g., user_id=-999). Your cache misses every time, so every request slams your database. This is called Cache Penetration or Cache Stampede.

Solution: Put a Bloom Filter in front of your cache. If the filter says "Definitely No," reject the request immediately without hitting the database. The attacker's DDoS fails. Your DB stays up. This is why companies like Twitter and Pinterest use Bloom Filters extensively.

Once I fell in love with Bloom Filters, I discovered they're part of a whole family of "good enough" data structures. In the big data world, trading a bit of accuracy for massive speed and memory savings is a common pattern.

Problem: "How many unique IP addresses visited our site today?" Storing 1 billion IPs in a set would require gigabytes.

HyperLogLog estimates cardinality (number of distinct elements) by observing the maximum number of leading zeros in hashed values. It's like estimating how many times someone flipped a coin by asking: "What's the longest streak of heads you saw?" If someone got 10 heads in a row, they probably flipped the coin thousands of times.

With just 12 KB, HyperLogLog can count 1 billion unique items with ~0.81% error. Redis commands: PFADD, PFCOUNT.

Bloom Filters answer "Is X in the set?" Count-Min Sketch answers "How many times did X appear?"

It uses a 2D array of counters and multiple hash functions. Hash collisions cause over-counting (false positives), but it never under-counts. You take the minimum across all hash functions to compensate. Great for "Top 10 trending hashtags" type queries.

Regular hash functions (SHA-256, MD5) produce completely different outputs if you change even one character (avalanche effect). SimHash does the opposite: similar documents produce similar hashes.

Google uses this to detect duplicate web pages among trillions of documents. By comparing Hamming distances between SimHash values, they can cluster similar content without comparing every pair of documents.

Not strictly probabilistic, but related. If you're distributing keys across 10 cache servers using key % 10, adding an 11th server reshuffles everything (cache apocalypse). Consistent Hashing arranges servers on a ring, so adding/removing a server only affects neighboring keys. Cassandra and DynamoDB use this extensively.

Q: Can you delete from a Bloom Filter? A: Not from a standard one. Use a Counting Bloom Filter or Cuckoo Filter.

Q: Why not just use a HashSet? A: Memory. 1 billion items in a HashSet = tens of gigabytes. Bloom Filter = hundreds of megabytes. If you can tolerate 1% errors, the cost savings are enormous.

Q: Why not use cryptographic hashes? A: Too slow. Bloom Filters need millions of hashes per second. Non-cryptographic hashes (MurmurHash, CityHash) are 10-100x faster.

Q: What's the biggest mistake people make? A: Underestimating the size of $m$ (bit array). If your dataset grows beyond your estimate, the false positive rate explodes. Always overestimate, or use a Scalable Bloom Filter.

Q: Real production story? A: Akamai (CDN) uses Bloom Filters to detect "one-hit wonders"—URLs accessed only once. If a URL is a one-hit wonder, they don't cache it to disk. This saved them 75% of disk writes. That's real money.