1. 프롤로그 - "수강신청 서버의 비극"

수강신청 날, 서버는 1대인데 1만 명이 동시에 접속합니다.

만약 서버가 "먼저 온 사람의 처리가 100% 끝날 때까지 다음 사람을 받지 않는다(FCFS)"라고 하면?

1등이 수강신청 하다가 화장실을 가면, 뒤에 9,999명은 영문도 모르고 무한 대기합니다. (Convoy Effect).

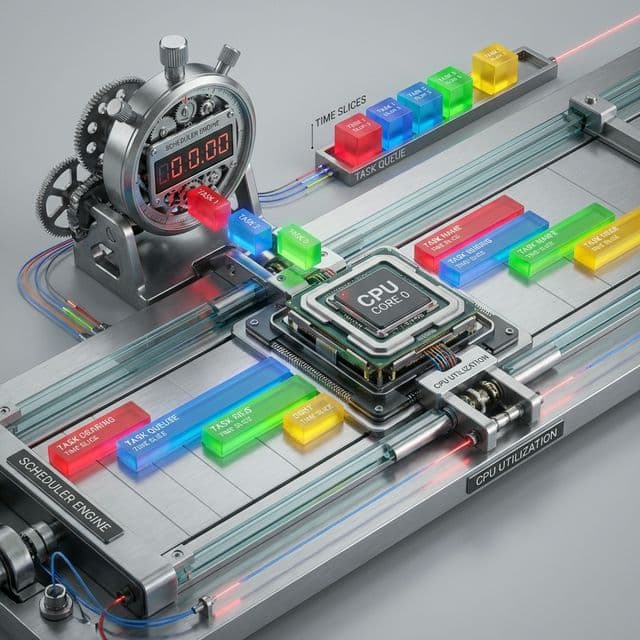

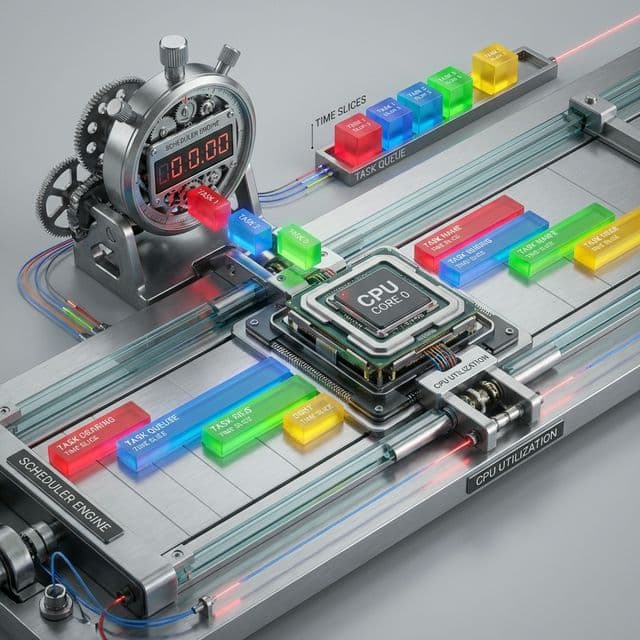

그래서 운영체제는 "조금씩 번갈아 가며 처리하기(Time Sharing)"를 도입했습니다.

사용자는 마치 자신만이 CPU를 독점하는 것처럼 느끼지만, 실제로는 1초에 수백 번씩 주인이 바뀌고 있습니다.

이 순서 정하기 놀이가 바로 CPU 스케줄링입니다.

2. 핵심 분류 - 뺏을 수 있는가?

가장 기본이 되는 기준입니다.

1) 비선점형 (Non-Preemptive)

-

"한번 잡으면 안 놓는다."

- 프로세스가 스스로 "나 다 했어" 하고 종료하거나 대기(I/O) 상태로 갈 때까지 CPU를 뺏지 않습니다.

- 장점: 문맥 교환(Context Switch) 오버헤드가 적음.

- 단점: 악성 루프에 빠진 프로그램 하나가 전체 시스템을 먹통으로 만듦. (Windows 3.1 시절 파란 화면의 주범).

- 알고리즘: FCFS, SJF.

2) 선점형 (Preemptive)

-

"시간 다 됐습니다. 내리세요."

- 운영체제가 강제로 개입해서 CPU를 빼앗습니다 (Interrupt).

- 장점: 응답성이 좋음 (마우스가 안 멈춤).

- 단점: 문맥 교환 비용 발생. 데이터 일관성 문제(Lock) 신경 써야 함.

- 알고리즘: Round Robin, SRT, MLFQ. (현대 OS는 99% 이거 씀).

3. 고전 알고리즘 열전

1. FCFS (First-Come, First-Served)

- 일명 선착순.

- 문제점: Convoy Effect (호위대 효과). 소요시간 긴 프로세스가 먼저 도착하면, 뒤에 있는 짧은 프로세스들이 하염없이 기다리는 현상. 평균 대기시간 최악.

- 비유하면, 편의점 계산대에서 카트 가득 물건을 가져온 사람이 앞에 서고, 음료 하나 사러 온 사람이 뒤에서 10분을 기다리는 꼴입니다.

2. SJF (Shortest Job First)

- 일명 짧은 놈 먼저.

- 이론적으로 평균 대기 시간을 최소화하는 최적의 알고리즘.

- 치명적 문제:

- Starvation (기아 현상): 실행 시간 100시간짜리 작업은 영원히 실행 안 됨. (계속 짧은 애들이 새치기하니까).

- 예측 불가: "이 작업이 얼마나 걸릴지" OS가 미리 알 방법이 없음. (신의 영역). 과거 실행 시간의 지수 이동 평균으로 추측하는 방법이 있지만, 정확하지 않습니다.

3. Round Robin (RR)

- 일명 돌려돌려 돌림판.

- Time Quantum (Time Slice): 각 프로세스에

10ms~100ms 정도의 시간만 줍니다. 시간 끝나면 쫓겨나고 맨 뒤로 갑니다.

- 핵심: Time Quantum의 크기.

- 너무 작으면? → 문맥 교환 오버헤드(

Switching Cost)가 실제 일하는 시간보다 커짐. (배보다 배꼽이 큼).

- 너무 크면? → FCFS랑 다를 바 없음. 응답성이 떨어짐.

- 현대 OS에서 가장 기본이 되는 알고리즘입니다.

4. Lottery Scheduling (추첨 스케줄링)

- 방식: 각 프로세스에게 '복권'을 나눠줍니다. 중요할수록 많이 줍니다.

- 실행: 매 Time Slice마다 랜덤으로 복권을 뽑습니다. 당첨된 프로세스가 CPU를 가집니다.

- 특징: 확률적으로 공정성을 보장합니다. 구현이 허무할 정도로 쉽지만, 랜덤성 때문에 실시간 시스템엔 못 씁니다.

- 의의: "공정성을 확률적으로 보장한다"는 발상 자체가 중요합니다. 우선순위 기반 스케줄링의 기아 현상을 자연스럽게 해결합니다. (복권을 1장이라도 가지고 있으면 언젠가는 당첨됨)

4. 현대의 해법: MLFQ (Multi-Level Feedback Queue)

"SJF처럼 짧은 작업은 빨리 끝내주고 싶고, RR처럼 공평하게도 하고 싶어."

그래서 나온 하이브리드 끝판왕입니다. 오늘날 대부분의 OS 스케줄러의 조상입니다.

동작 원리

- 여러 개의 큐를 둡니다. (Q1: 상류층, Q2: 중산층, Q3: 서민층).

- 모든 프로세스는 처음에 Q1 (최상위)으로 들어갑니다.

- Q1은 Short Time Slice (RR)를 줍니다.

- 여기서 다 못 끝내면? "너 좀 오래 걸리는 놈이구나" 하고 Q2로 강등당합니다.

- Q2, Q3로 내려갈수록 자주 실행되진 못하지만, 한번 잡으면 길게(Long Slice) 줍니다.

- Aging (기아 방지): 너무 오래 아래쪽 큐에 박혀있는 놈은 다시 Q1으로 승격시켜 줍니다. ("패자부활전").

결과: 짧은 작업(I/O bound, 키보드 입력 등)은 Q1에서 즉시 처리되어 반응속도가 빠르고, 긴 작업(CPU bound, 렌더링)은 아래쪽에서 묵묵히 돌아갑니다.

MLFQ의 악용 방지

초기 MLFQ에는 허점이 있었습니다. 악의적인 프로세스가 타임 슬라이스가 끝나기 직전에 의도적으로 I/O 요청을 보내면, 계속 Q1에 머물면서 CPU를 독점할 수 있었습니다.

해결책: 주기적 Boost. 일정 시간마다 모든 프로세스를 Q1으로 올립니다. 이렇게 하면 악용이 어려워지고, Starvation도 방지됩니다.

5. Linux의 선택: CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler)

리눅스(커널 2.6.23 이후)는 MLFQ 대신 CFS를 씁니다. O(1) 스케줄러를 대체했습니다.

1) 철학 - "공산주의 스케줄링"

- 우선순위 큐 같은 복잡한 거 말고, 그냥 실행 시간(vruntime)을 똑같이 맞춰주자.

- "너 CPU 3초 썼어? 쟤는 1초밖에 안 썼네? 비켜."

2) 구조: Red-Black Tree

- 실행 대기 중인 프로세스들을 Red-Black Tree (이진 탐색 트리의 일종)에 넣습니다.

- 정렬 기준:

vruntime (가상 실행 시간).

- 트리의 가장 왼쪽 (Leftmost):

vruntime이 가장 작은, 즉 가장 굶주린 프로세스.

- 스케줄러는 항상 가장 왼쪽 놈을 꺼내서 실행합니다.

- 실행된 프로세스는

vruntime이 증가하고, 다시 트리의 적절한 위치(오른쪽)로 삽입됩니다.

3) 성능

- 프로세스 선택: $O(1)$ (캐싱된 포인터)

- 프로세스 삽입/삭제: $O(\log N)$

- 수천 개의 프로세스가 있어도 1초에 수백 번 교체하는 데 무리가 없습니다.

4) 우선순위(Nice) 처리

CFS에서도 우선순위는 존재합니다. nice 값(-20 ~ +19)에 따라 vruntime의 증가 속도가 달라집니다.

우선순위가 높은 프로세스는 vruntime이 천천히 증가하기 때문에 트리의 왼쪽에 더 오래 머물고, 결과적으로 CPU를 더 많이 받습니다.

6. 실제 Case Study - 화성 탐사선 패스파인더 (Priority Inversion)

스케줄링의 유명한 버그 시나리오입니다. 1997년 NASA의 화성 탐사선 Mars Pathfinder에서 실제로 발생했습니다.

사건 경위

- Low 우선순위 프로세스가

Lock(A)를 잡고 데이터를 씀.

- High 우선순위 프로세스가 등장해서

Lock(A)를 원함. (Low가 놔줄 때까지 대기).

- 이때 갑자기 Medium 우선순위 프로세스가 등장.

- Medium은 High보다 낮지만 Low보다 높음. 그래서 CPU를 차지하고 신나게 돔.

- 결과: High는 Medium 때문에 영원히 기다림. (Low가 CPU를 못 받으니 Lock을 못 푸니까).

화성에서의 증상

패스파인더의 정보 버스 태스크(High)가 블로킹되어 타이머가 만료되고, 시스템이 리셋을 반복했습니다. 지구에서 디버깅 결과 Priority Inversion이 원인이라는 것이 밝혀졌고, 원격으로 패치를 전송했습니다.

해결책 - Priority Inheritance (우선순위 상속)

Lock을 가진 Low의 우선순위를 일시적으로 High만큼 올려줘서, Medium에게 선점당하지 않고 빨리 Lock을 해제할 수 있게 만듭니다. Lock을 해제하면 원래 우선순위로 복귀합니다.

이 사건은 "스케줄링은 이론으로 완벽해도 실제로 무너질 수 있다"는 교훈을 줍니다.

7. 스케줄링 성능 지표 - 무엇을 최적화할 것인가?

스케줄링 알고리즘을 평가하는 핵심 지표들:

- Throughput (처리량): 단위 시간당 완료된 프로세스 개수. 시스템 입장의 효율성.

- Turnaround Time (반환 시간): 작업 제출부터 완료까지 걸린 총 시간. (대기시간 + 실행시간).

- Response Time (응답 시간): 첫 번째 출력이 나올 때까지 걸리는 시간. UI 반응성에 직결.

- Waiting Time (대기 시간): 프로세스가 Ready Queue에서 기다린 총 시간.

문제는 이 지표들이 서로 트레이드오프 관계에 있다는 것입니다.

Throughput을 높이려면 Context Switch를 줄여야 하는데, 그러면 Response Time이 나빠집니다.

Response Time을 높이려면 자주 스위칭해야 하는데, 그러면 Throughput이 떨어집니다.

어떤 지표를 중시하느냐에 따라 최적의 알고리즘이 달라집니다:

- 서버: Throughput 중시 → 긴 Time Quantum.

- 데스크톱: Response Time 중시 → 짧은 Time Quantum.

- 실시간 시스템 (RTOS): Deadline 보장이 최우선.

8. 용어 사전 (Glossary)

- Context Switch (문맥 교환): CPU가 실행 중인 프로세스를 바꾸기 위해 현재 상태(레지스터 값 등)를 저장하고 다음 프로세스 상태를 불러오는 작업.

- Starvation (기아): 우선순위 낮은 프로세스가 무한히 CPU 할당을 못 받는 상태. → Aging으로 해결.

- I/O Bound Process: 계산보다 입출력(대기)이 많은 프로세스. (워드, 웹브라우저). → 우선순위 높여야 함.

- CPU Bound Process: 계산이 주구장창 많은 프로세스. (동영상 인코딩, 딥러닝).

- Priority Inversion: 높은 우선순위 태스크가 낮은 우선순위 태스크의 Lock 때문에 블로킹되는 현상.

- Aging: 기아 상태인 프로세스의 우선순위를 시간이 지남에 따라 올려주는 기법.

9. FAQ & Common Questions

-

Q: 스레드 스케줄링은 프로세스와 다른가요?

- A: 리눅스에서는 스레드도 Light Weight Process (LWP)로 취급하여 프로세스와 똑같이 스케줄링합니다. 다만 같은 프로세스 내 스레드 전환은 메모리 영역(Code, Data, Heap)을 공유하므로 문맥 교환 비용이 훨씬 쌉니다.

-

Q: 문맥 교환이 잦으면 왜 안 좋은가요?

- A: 1) 레지스터 저장/복원 비용. 2) 캐시 오염(Cache Pollution). 새 프로세스가 오면 L1/L2 캐시를 다 갈아엎어야 해서 성능이 급락합니다. TLB(Translation Lookaside Buffer) 역시 플러시되어 가상 메모리 번역이 느려집니다.

-

Q: 싱글 코어에서 멀티태스킹은 어떻게 구현되나요?

- A: Time Slicing. 아주 짧은 시간(10ms)마다 프로세스를 교체합니다. 인간의 눈에는 동시에 실행되는 잔상으로 보입니다.

CPU Scheduling: The Art of Fairness

1. Prologue: "One Brain, Many Thoughts"

Imagine a single chef (the CPU) in a busy restaurant kitchen.

If the chef chops onions for 1 hour straight while the steak burns and the soup boils over, the restaurant collapses. That's FCFS (First-Come, First-Served) scheduling — whatever arrived first gets all the attention until it's completely done.

The solution: the chef chops onions for 5 seconds, flips the steak, stirs the soup, then goes back to onions. This constant switching creates the illusion of parallelism — all dishes seem to be cooking at the same time, even though there's only one chef.

CPU is one, but programs are many. Chrome, Spotify, and VS Code all appear to run "at the same time." It's a magic trick called Time Sharing: the OS switches execution context every few milliseconds, so fast that humans can't tell.

This deciding who runs next is CPU Scheduling.

2. The Fundamental Question: Can You Take It Away?

The first question in any OS interview.

Non-Preemptive (Cooperative)

-

"I will yield CPU when I'm done."

- The OS never forcibly takes control. The running process must voluntarily give up the CPU.

- Dangerous: If a process enters

while(true), the entire OS freezes. This was the reality in older systems (Windows 3.1, early Mac OS) — one rogue program could crash everything.

- Algorithms: FCFS, SJF.

Preemptive

-

"Time's up. Get out."

- The OS sets a timer interrupt. When the timer fires, the OS forcibly regains control and decides what to run next.

- Pros: Responsive (mouse never freezes). No single process can monopolize the CPU.

- Cons: Context switching cost. Must handle data consistency issues (locks, race conditions).

- Algorithms: Round Robin, SRT, MLFQ. All modern OSes (Windows 10, macOS, Linux, Android) use preemptive scheduling.

3. Classic Algorithms

FCFS (First-Come, First-Served)

- Simple queue structure — first in, first out.

- Convoy Effect: A huge truck (big process) blocks the single lane, causing a traffic jam for Ferraris (small processes) behind it. Average waiting time is terrible.

- Analogy: Standing behind someone with a full cart at the convenience store when you just want one drink.

SJF (Shortest Job First)

- Run the shortest job first. Mathematically optimal for minimizing average waiting time.

- Fatal flaws:

- Starvation: Long jobs may never run if short jobs keep arriving.

- Impossible to implement perfectly: The OS cannot predict the future. "How long will this

gcc compilation take?" — nobody knows. The best approximation is exponential moving average of past burst times, but it's still a guess.

Round Robin (RR)

- Give everyone a Time Quantum (e.g., 20ms). When time's up, the process goes to the back of the queue.

- Fair and responsive.

- The critical trade-off:

- Quantum too small (1ms): You spend more time context switching than computing. Overhead eats all performance.

- Quantum too large (10s): Feels laggy, effectively degrades to FCFS.

- This is the foundation of scheduling in all modern operating systems.

Lottery Scheduling

- Each process gets "lottery tickets." Higher priority = more tickets.

- Every time slice, a random ticket is drawn, and the winner gets the CPU.

- Elegant simplicity: Naturally prevents starvation (any process with even 1 ticket will eventually win). Probabilistically fair. But randomness makes it unsuitable for hard real-time systems.

- Its significance: the idea of probabilistic fairness — rather than strict priority rules, let probability handle distribution.

4. The Modern Solution: MLFQ (Multi-Level Feedback Queue)

"I want SJF's speed for short jobs AND Round Robin's fairness." This hybrid approach became the ancestor of most modern OS schedulers.

How It Works

- Create multiple queues with decreasing priority: Q1 (VIP), Q2 (Standard), Q3 (Economy).

- All new processes start in Q1 (highest priority).

- Q1 uses short time slices (RR). If a process finishes within its slice — great, it was a short job. If not, it gets demoted to Q2: "You must be a long-running task."

- Lower queues give longer time slices but run less frequently. Q3 might give 100ms per turn but only runs when Q1 and Q2 are empty.

- Aging (anti-starvation): Processes stuck in lower queues for too long get promoted back to Q1 — a "loser's bracket comeback."

Result: Interactive jobs (typing, mouse clicks, UI) stay in Q1 with fast response times. Background jobs (video encoding, downloads) sink to lower queues but get generous time slices when they do run.

Preventing Gaming the System

Early MLFQ had a vulnerability: a malicious process could deliberately issue an I/O request just before its time slice expired, staying permanently in Q1 and hogging the CPU.

Solution: Periodic boost — at regular intervals, push ALL processes back to Q1. This makes gaming difficult and simultaneously prevents starvation.

5. Linux's Choice: CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler)

Linux (kernel 2.6.23+) ditched MLFQ-style queues in favor of CFS, replacing the older O(1) scheduler.

Philosophy: "Communist Scheduling"

Instead of complex priority queues, CFS takes a radical approach: track how much CPU time each process has consumed (vruntime — virtual runtime) and always run the process that has consumed the least.

"You've used 3 seconds of CPU? That process has only used 1 second? Step aside."

Data Structure: Red-Black Tree

- All runnable processes are stored in a Red-Black Tree (a self-balancing binary search tree).

- Sorted by

vruntime.

- Leftmost node: The process with the smallest

vruntime — the "hungriest" process.

- The scheduler always picks the leftmost node to run next.

- After running, a process's

vruntime increases, and it gets reinserted to the right side of the tree.

Performance

- Process selection: $O(1)$ (cached leftmost pointer)

- Process insertion/deletion: $O(\log N)$

- Handles thousands of processes with hundreds of context switches per second without breaking a sweat.

Priority via Nice Values

CFS still supports priorities through nice values (-20 to +19). Higher priority processes have their vruntime tick slower, so they stay on the left side of the tree longer and receive more CPU time. Lower priority processes accumulate vruntime faster and drift to the right.

6. Case Study: Mars Pathfinder (Priority Inversion)

One of the most famous scheduling bugs in history — and it happened on another planet.

What Happened (1997)

- A Low priority task acquired

Lock(A) to write data.

- A High priority task needed

Lock(A) and blocked, waiting for Low to release it.

- A Medium priority task arrived. Since Medium > Low, Medium preempted Low and started running.

- Result: High was stuck indefinitely. Low couldn't run (Medium kept preempting it), so Low couldn't release the lock, so High couldn't proceed.

The Symptoms on Mars

The Pathfinder's information bus task (High priority) kept getting blocked, causing watchdog timers to fire and the system to repeatedly reset itself. Engineers on Earth diagnosed the issue remotely as Priority Inversion and uploaded a patch — across millions of miles of space.

Solution: Priority Inheritance

When a high-priority task blocks on a lock held by a low-priority task, temporarily boost the lock-holder's priority to match the blocked task's priority. This prevents medium-priority tasks from preempting the lock-holder, allowing it to finish quickly and release the lock. Once the lock is released, the priority returns to normal.

This incident teaches us: scheduling that's perfect in theory can break catastrophically in practice.

7. Scheduling Performance Metrics

How do we evaluate a scheduling algorithm? There are several key metrics, and they often conflict with each other:

- Throughput: Number of processes completed per unit time. The system's perspective.

- Turnaround Time: Total time from job submission to completion (waiting time + execution time).

- Response Time: Time until the first output appears. Critical for UI responsiveness.

- Waiting Time: Total time a process spends in the ready queue.

The problem is these metrics are in a trade-off relationship:

- Better throughput → less context switching → worse response time.

- Better response time → more frequent switching → worse throughput.

The optimal algorithm depends on what you prioritize:

- Servers: Throughput-focused → longer time quanta.

- Desktops: Response time-focused → shorter time quanta.

- Real-time systems (RTOS): Deadline guarantee above all else.

8. Glossary

- Context Switch: Saving the current process's state (registers, program counter) and loading the next process's state. Pure overhead.

- Starvation: A low-priority process never getting CPU time because higher-priority processes keep arriving. Solved by Aging.

- I/O Bound Process: A process that spends more time waiting for I/O than computing (text editors, web browsers). Should get high priority.

- CPU Bound Process: A process that's computation-heavy (video encoding, deep learning).

- Priority Inversion: When a high-priority task is blocked because a low-priority task holds a needed lock.

- Aging: Gradually increasing the priority of long-waiting processes to prevent starvation.