Technical Debt: Borrowing from the Future

Quick & Dirty code feels fast now, but you pay interest later. Don't go bankrupt.

Quick & Dirty code feels fast now, but you pay interest later. Don't go bankrupt.

Why does my server crash? OS's desperate struggle to manage limited memory. War against Fragmentation.

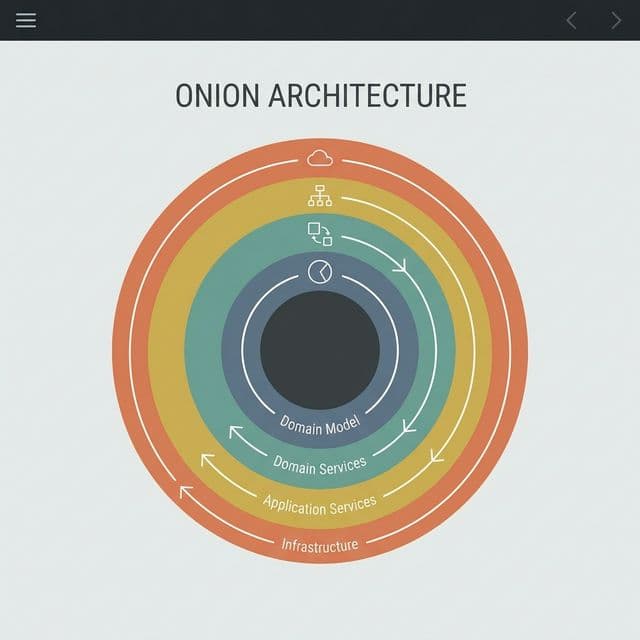

A deep dive into Robert C. Martin's Clean Architecture. Learn how to decouple your business logic from frameworks, databases, and UI using Entities, Use Cases, and the Dependency Rule. Includes Screaming Architecture and Testing strategies.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

Fast by name. Partitioning around a Pivot. Why is it the standard library choice despite O(N²) worst case?

When I started my first startup, I faced the same choice every night. I heard our competitor was launching next week, and our product was barely half-done. Looking at the code, I knew doing this properly would take 3 days.

"Let me just... hard-code this for now. I'll fix it later."

I muttered to myself as I typed. Copy-paste 10 times, nest 20 if-statements, name variables temp1, temp2, final_final_v2, and boom—it worked. The demo succeeded. We got funded. But 3 months later, I cursed past-me.

Touching one line broke three features. Adding a new feature took a week. The debt I took on had returned with interest. This is Technical Debt.

Technical debt was first coined by Ward Cunningham in 1992. He compared it to financial debt. Just like you take a mortgage to buy a house earlier, you sacrifice code quality to ship faster.

Here's the key: debt itself isn't bad. You borrow money to buy a house, live in it while earning salary, and eventually pay it off for net gain. But if you ignore the interest, it compounds and you go bankrupt. Code is the same.

At first, you develop fast. Later, modifying that code takes 10x the time. That's the interest. And if you ignore it, eventually someone says "it would be faster to rewrite from scratch." That's bankruptcy.

Martin Fowler categorized technical debt into 4 types. Mapping my experience to his model, everything clicked.

1. Reckless & Deliberate "I don't know what design is, and as long as it works, who cares." This was me as a junior. I didn't know design patterns. I just coded. This isn't debt, it's gambling.

2. Prudent & Deliberate "We need to ship this week. Let's hard-code it now and refactor next sprint." This is strategic debt. If you can tell leadership "I can make this perfect in 2 weeks, or ship dirty code in 1 week—but we'll need time to pay it back in a month," that's good debt.

3. Reckless & Inadvertent

"SOLID principles? I've heard of them but didn't apply them here."

Debt from lack of skill. When I first learned React, I dumped all state globally. Later I experienced useContext hell.

4. Prudent & Inadvertent "Oh, this is how I should have done it. Now I know." You did your best initially, but later learned a better way. This is unavoidable. It's a byproduct of learning.

Signs that your code is rotting are called Code Smells. The ones I've encountered most:

1. Duplicated Code The same logic copy-pasted in 5 places. To fix a bug, you touch all 5. That's 500% interest.

2. Long Method A 200-line function. You scroll 3 times to see the end. Without comments, nobody knows what it does.

3. Large Class One class with 50 methods. This isn't a class, it's a department store.

4. Shotgun Surgery To change one thing, you open 10 files. Dependencies tangled like spaghetti.

5. Magic Number

if (status === 3) What's 3? Nobody knows. Not even me 6 months later.

In finance, compound interest is scary because you pay "interest on interest." Code is identical.

At first: "This function takes 10 minutes more to fix. Whatever." A month later: "Touching this breaks 3 tests. Let's just copy-paste." 3 months later: "Nobody can touch this module. It's legacy." A year later: "Rewriting is faster."

This actually happened to me. What would have taken 3 hours to refactor early became a 2-week rewrite project because I kept delaying it.

You pay debt through Refactoring. You keep the external behavior the same while improving the internal structure.

For example, imagine you had this code:

function processOrder(order) {

let total = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < order.items.length; i++) {

if (order.items[i].type === 'book') {

if (order.items[i].price > 50) {

total += order.items[i].price * 0.9;

} else {

total += order.items[i].price * 0.95;

}

} else if (order.items[i].type === 'electronics') {

if (order.items[i].price > 100) {

total += order.items[i].price * 0.85;

} else {

total += order.items[i].price * 0.92;

}

} else {

total += order.items[i].price;

}

}

if (order.customer.isPremium) {

total = total * 0.95;

}

if (total > 200) {

total = total - 20;

}

return total;

}

This code works. But adding a new product type or changing discount logic would be hell. After refactoring:

function processOrder(order) {

const subtotal = calculateSubtotal(order.items);

const discounted = applyCustomerDiscount(subtotal, order.customer);

const final = applyBulkDiscount(discounted);

return final;

}

function calculateSubtotal(items) {

return items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + getPriceWithDiscount(item), 0);

}

function getPriceWithDiscount(item) {

const discountRate = getDiscountRate(item);

return item.price * (1 - discountRate);

}

function getDiscountRate(item) {

const rates = {

book: { highPrice: 0.1, lowPrice: 0.05, threshold: 50 },

electronics: { highPrice: 0.15, lowPrice: 0.08, threshold: 100 },

default: { highPrice: 0, lowPrice: 0, threshold: 0 }

};

const config = rates[item.type] || rates.default;

return item.price > config.threshold ? config.highPrice : config.lowPrice;

}

function applyCustomerDiscount(amount, customer) {

return customer.isPremium ? amount * 0.95 : amount;

}

function applyBulkDiscount(amount) {

return amount > 200 ? amount - 20 : amount;

}

Did the code get longer? Yes. But now to add a new product type, I just add one line to the rates object. To change discount logic, I modify that specific function. This is what paying off debt looks like.

"Leave the campground cleaner than you found it."

Same with code. It's called the Boy Scout Rule. When you open a file, improve it a little before leaving. Rename one variable, add one comment, extract one function. Anything helps.

I try to practice this. I go in to fix a bug, but on my way out, I rename 3 variables, extract magic numbers into constants, and pull duplicated code into a function. Invest 5 minutes daily, and after a year, the difference is massive.

You need to know the debt exists to pay it off. Here's how I track it:

1. TODO Comments// TODO: Refactor this logic into Strategy pattern later

// FIXME: N+1 query problem, change to batch next sprint

// HACK: Temporary workaround, implement properly next sprint

But honestly, TODO comments are graveyards. Once written, never revisited.

2. Issue Trackers I use "Tech Debt" labels in Jira or GitHub Issues. When planning sprints, I allocate 20% to debt resolution. Non-negotiable.

3. Tools like SonarQube They measure code quality automatically. Reports like "This file has excessive complexity" or "30% duplicated code." Numbers are persuasive.

I follow the 20% Rule. 80% of sprint time for new features, 20% for refactoring and debt paydown. If this breaks, velocity halves in 3 months. I learned this the hard way.

When debt piles up, the temptation is "let's just rewrite." I've felt it too. But most of the time, rewrites fail.

Why?

Instead, do incremental refactoring. Replace one feature, one module at a time. Like replacing wheels on a moving train. This is called the Strangler Fig Pattern—a metaphor for a plant that slowly wraps around and replaces a large tree.

This is the hardest part. Tell the CEO or PM "this sprint has no features, just refactoring," and the response is predictable:

"Does the user see this? Does it help revenue?"

Here's how I explain it:

Car Metaphor: "Our code is like a car that hasn't had an oil change in 3 years. It's running now, but the engine might blow next month. Give me one day to change the oil, and we're safe for 6 months."

House Metaphor: "The wall has cracks, but we keep repainting over them. Eventually, it'll collapse. Invest 2 weeks now to reinforce the foundation, and we can add a second floor."

Interest Metaphor: "This code is a 50% APR loan. Right now, adding one feature takes a week. In 3 months, it'll take 3 weeks. Invest 1 week now to pay off the debt, and it stays 1 week forever."

Showing numbers is most powerful. "Last quarter we shipped 10 features. This quarter only 5. Velocity halved. Technical debt is why."

Technical debt is unavoidable. We never have time for perfect code, requirements constantly change, and our skills grow. What matters is acknowledging the debt, managing it, and paying it systematically.

Now when I hard-code at 2 AM, I'm not making a deal with the devil—I'm making a contract with future-me. "This week I ship fast. Next week I spend two days refactoring." And I actually pay it back.

Don't go bankrupt. Pay your interest. Then debt becomes a tool for growth.