SOLID Principles: 5 Commandments to Avoid Bad Code

SRP, OCP, LSP, ISP, DIP. The foundation of maintainable software architecture. Examples in TypeScript.

SRP, OCP, LSP, ISP, DIP. The foundation of maintainable software architecture. Examples in TypeScript.

Why does my server crash? OS's desperate struggle to manage limited memory. War against Fragmentation.

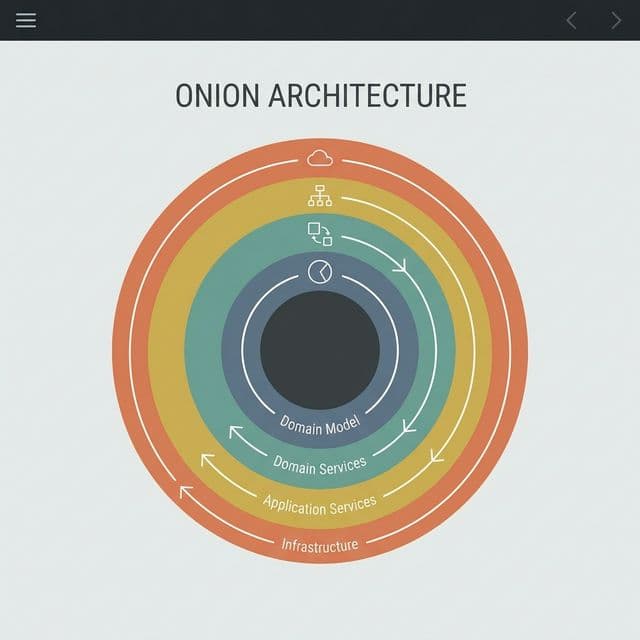

A deep dive into Robert C. Martin's Clean Architecture. Learn how to decouple your business logic from frameworks, databases, and UI using Entities, Use Cases, and the Dependency Rule. Includes Screaming Architecture and Testing strategies.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

Fast by name. Partitioning around a Pivot. Why is it the standard library choice despite O(N²) worst case?

A senior engineer looked at my code during a review and sighed.

"Your

UserServiceis handling user registration, email sending, logging, and payment processing. What happens when we switch email providers?"

Me: "I guess... we change the UserService?"

Senior: "And risk breaking user registration, logging, and payments in the process? You just violated all 5 SOLID principles."

I didn't get it at first. I thought shorter files were better. I thought "one big class" was simpler than "five small classes." I was completely wrong. What matters is not the length of the code but how safe it is to change.

That's when I started learning SOLID the hard way—through production bugs, failed deployments, and late-night debugging sessions.

I came from a non-technical background. When I started building my own product, I thought design patterns were "unnecessary complexity" invented by academics. I was wrong. SOLID isn't about being clever—it's about surviving change.

Here's what happened: We needed to add a new payment method (Kakao Pay) to our checkout flow. Simple, right? Wrong. Our PaymentService was 1,500 lines of if-else spaghetti. Adding Kakao Pay broke Toss payments. Why? Because everything shared state. That's tight coupling in action.

If I had followed SOLID from the start, adding Kakao Pay would've been a new file, not a refactor of the entire payment system.

"A class should have only one reason to change."

This is the most intuitive principle, but the hardest to follow in practice. The word "responsibility" is vague. I used to think "handling user registration" was a single responsibility. But Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob) defines it differently: a class should have only one reason to change.

Let's say your UserService does three things:

That's three reasons to change:

If you change the email logic and accidentally break user registration, that's an SRP violation.

class UserService {

register(user: User) {

db.save(user);

emailClient.send(user.email, "Welcome!");

logger.log("User registered");

}

}

I wrote code like this. It was convenient at first. Then I changed the email template to HTML and accidentally broke the db.save() call with a typo. Registration stopped working. That's when I understood: when a class does too many things, fixing one thing breaks another.

class UserService {

constructor(

private userRepository: UserRepository,

private emailService: EmailService,

private logger: Logger

) {}

register(user: User) {

this.userRepository.save(user);

this.emailService.sendWelcome(user);

this.logger.log("User registered");

}

}

Now you can change EmailService without touching UserRepository. Each class has one job. That's SRP.

In frontend development, SRP applies to components too. I used to build components like this:

// Bad: God Component

function UserProfile() {

const [user, setUser] = useState();

const [loading, setLoading] = useState(false);

// Fetching logic

useEffect(() => {

fetch('/api/user').then(setUser);

}, []);

// Rendering logic

return loading ? <Spinner /> : (

<div>

<img src={user.avatar} />

<h1>{user.name}</h1>

<button onClick={() => updateUser()}>Edit</button>

</div>

);

}

This component does too much: fetches data, handles loading state, renders UI, and handles updates. If the API changes, this component breaks. If the UI design changes, this component breaks.

Better approach:

// Good: Separated Concerns

function useUser() {

const [user, setUser] = useState();

useEffect(() => {

fetch('/api/user').then(setUser);

}, []);

return user;

}

function UserProfile() {

const user = useUser(); // Data fetching separated

return <UserCard user={user} />; // UI separated

}

Now you can change the data-fetching logic (switch to React Query, for example) without touching the UI component.

"Open for extension, closed for modification."

This was the coolest principle I learned. It sounds like magic: "Add features without changing existing code? How?"

Then I hit the if-else hell.

class PaymentProcessor {

pay(type: string, amount: number) {

if (type === 'CARD') {

this.payCard(amount);

} else if (type === 'PAYPAL') {

this.payPaypal(amount);

} else if (type === 'BITCOIN') {

this.payBitcoin(amount);

}

}

}

When we needed to add Toss Pay, I added else if (type === 'TOSS'). I deployed it. Kakao Pay broke. Why? I messed up a bracket while editing. Editing existing code introduces risk.

interface PaymentMethod {

pay(amount: number): void;

}

class CardPayment implements PaymentMethod {

pay(amount: number) { /* card logic */ }

}

class PaymentProcessor {

pay(paymentMethod: PaymentMethod, amount: number) {

paymentMethod.pay(amount); // No changes needed!

}

}

Now, adding Toss Pay means creating a new TossPayment class. The PaymentProcessor doesn't change. Existing tests still pass. That's OCP.

Modern plugin systems (WordPress, Webpack, VS Code extensions) all follow OCP. You add plugins without modifying core code.

// Bad: Hardcoded Logic

function NotificationBanner({ type }: { type: string }) {

if (type === 'error') return <ErrorBanner />;

if (type === 'warning') return <WarningBanner />;

if (type === 'success') return <SuccessBanner />;

}

Every time you add a new notification type, you modify this component. Instead:

// Good: Component Injection

function NotificationBanner({ component: Component }) {

return <Component />;

}

// Usage

<NotificationBanner component={ErrorBanner} />

<NotificationBanner component={CustomBanner} /> // New type, no changes!

"Child classes must be substitutable for their parent classes."

This is the hardest SOLID principle to grasp. I thought "if Square inherits from Rectangle, they're substitutable, right?" Wrong. The famous Square-Rectangle problem illustrates this.

Mathematically, a square is a rectangle. So this should work, right?

class Rectangle {

setWidth(w: number) { this.width = w; }

setHeight(h: number) { this.height = h; }

}

class Square extends Rectangle {

setWidth(w: number) { this.width = w; this.height = w; } // Maintain squareness

setHeight(h: number) { this.width = h; this.height = h; }

}

function resize(rect: Rectangle) {

rect.setWidth(10);

rect.setHeight(5);

console.log(rect.getArea()); // Expects 50

}

If you pass a Square, the area is 25, not 50. The function expects to set width and height independently. Square breaks that expectation. That's an LSP violation.

Lesson learned: Mathematical relationships don't always translate to inheritance relationships in code.

Break the inheritance. Use composition or separate interfaces. Modern languages like Go and Rust don't even have class inheritance, partly to avoid LSP issues.

"Clients shouldn't depend on methods they don't use."

I violated this when building an admin panel. I created a big AdminInterface:

interface AdminInterface {

viewUsers(): void;

deleteUsers(): void;

editContent(): void;

approvePayments(): void;

}

The problem? Our "Content Manager" role only needed editContent(), but had to implement all four methods. I ended up throwing errors:

class ContentManager implements AdminInterface {

editContent() { /* real logic */ }

deleteUsers() { throw new Error("Not authorized"); } // Forced implementation

}

If you're throwing "Not Implemented" errors, your interface is too fat.

interface UserManager { viewUsers(): void; deleteUsers(): void; }

interface ContentEditor { editContent(): void; }

interface PaymentApprover { approvePayments(): void; }

class ContentManager implements ContentEditor {

editContent() { /* only this */ }

}

Don't force clients to plug in USB, HDMI, and VGA when they only need power.

"Depend on abstractions, not concretions."

DIP is the crown jewel of SOLID. Understanding this unlocks why Dependency Injection exists and why frameworks like Spring and NestJS provide DI containers.

I had a weather app that read from a Samsung sensor:

class WeatherTracker {

private sensor: SamsungSensor; // Tightly coupled!

constructor() {

this.sensor = new SamsungSensor();

}

}

When we needed to support LG sensors, I had to modify WeatherTracker. That's tight coupling.

The "inversion" part confused me at first. Here's what it means: traditionally, WeatherTracker depends on SamsungSensor (concrete class). We invert that dependency by making WeatherTracker depend on a Sensor interface (abstraction).

interface Sensor {

getTemperature(): number;

}

class WeatherTracker {

constructor(private sensor: Sensor) {} // Injected from outside

}

const tracker = new WeatherTracker(new SamsungSensor());

Now swapping sensors is trivial. Testing is easy too—just inject a MockSensor.

// Bad: Hard-coded API

function UserList() {

const [users, setUsers] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

fetch('/api/users').then(setUsers); // Tightly coupled to this API

}, []);

return <ul>{users.map(u => <li>{u.name}</li>)}</ul>;

}

If you want to switch to GraphQL or mock data for testing, you have to change UserList.

// Good: Inject the data-fetching function

function UserList({ fetchUsers }: { fetchUsers: () => Promise<User[]> }) {

const [users, setUsers] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

fetchUsers().then(setUsers); // Abstraction

}, []);

return <ul>{users.map(u => <li>{u.name}</li>)}</ul>;

}

// Usage

<UserList fetchUsers={() => fetch('/api/users')} />

<UserList fetchUsers={mockFetchUsers} /> // Testing

Here's a mistake I made: I wrote a 50-line admin script and tried to apply SOLID. I created UserRepository interfaces, EmailService interfaces... The script became 300 lines and 10 files.

A senior engineer laughed: "This is a one-time throwaway script. Why so complicated?"

Lesson learned: SOLID is for code that changes frequently. Don't apply it to:

Follow YAGNI (You Aren't Gonna Need It) for these. Refactor to SOLID when change is needed, not preemptively.

But for core business logic (payments, authentication, orders)? SOLID is mandatory. Those parts change constantly and bugs are costly.

| Principle | What It Means | When It Saves You |

|---|---|---|

| SRP | One class, one reason to change | Debugging (changing email logic doesn't break DB) |

| OCP | Add features without editing existing code | Safe extensions (new payment methods don't break old ones) |

| LSP | Child classes must honor parent contracts | Predictability (subclasses behave as expected) |

| ISP | Split fat interfaces into thin ones | Flexibility (clients only depend on what they need) |

| DIP | Depend on abstractions, not implementations | Testability & flexibility (swap implementations easily) |

SOLID isn't about writing perfect code on the first try. It's about writing code that survives change. I learned these principles the hard way—through production bugs, broken deployments, and frustrated teammates.

If you're a non-CS founder like me, building your own product, SOLID might feel like "academic overhead" at first. But trust me: the first time you swap a payment provider in 5 minutes instead of 5 days, you'll understand why SOLID matters.