Search System Design: Elasticsearch vs Building Your Own

Started with SQL LIKE, hit its limits, moved to Elasticsearch, and got shocked by operational costs. The real trade-offs of search systems.

Started with SQL LIKE, hit its limits, moved to Elasticsearch, and got shocked by operational costs. The real trade-offs of search systems.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

Foundation of DB Design. Splitting tables to prevent Anomalies. 1NF, 2NF, 3NF explained simply.

Learn BST via Up & Down game. Why DBs use B-Trees over Hash Tables. Deep dive into AVL, Red-Black Trees, Splay Trees, and Treaps.

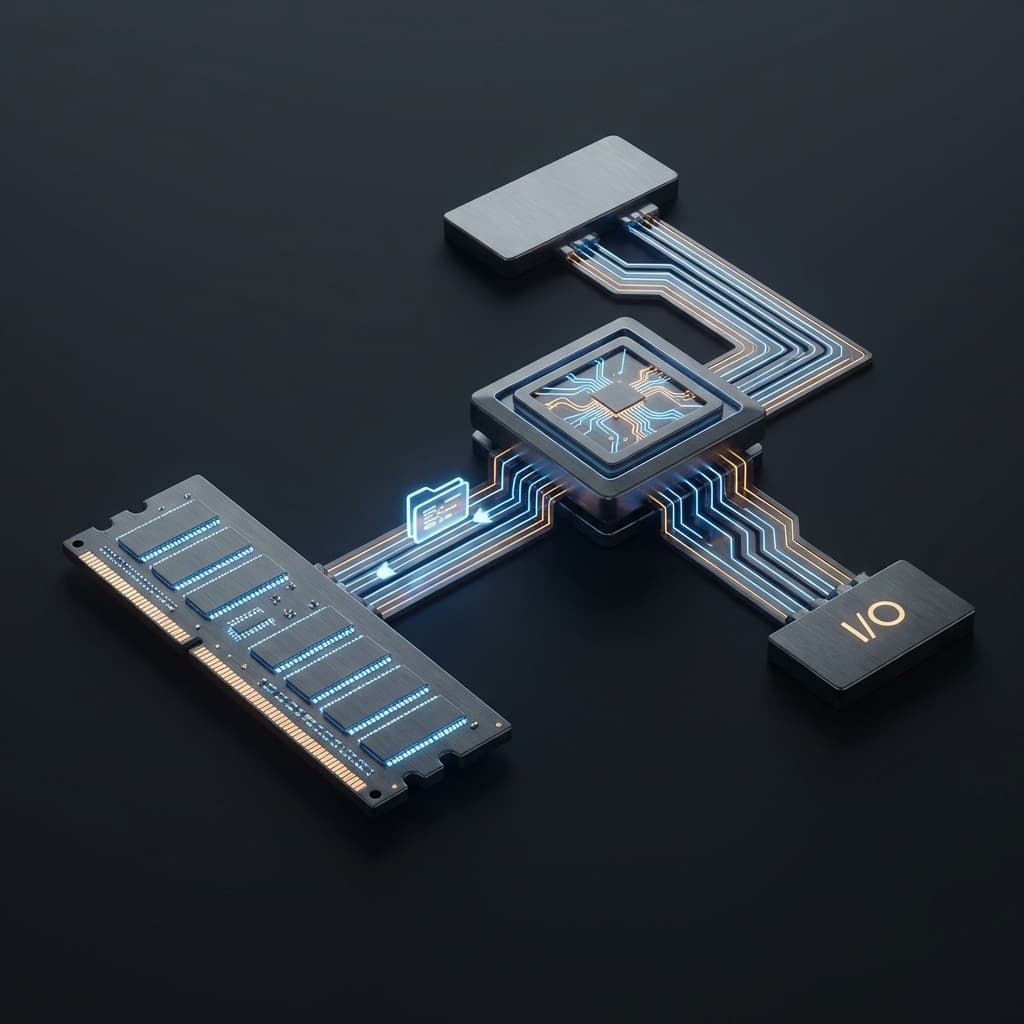

Why is the CPU fast but the computer slow? I explore the revolutionary idea of the 80-year-old Von Neumann architecture and the fatal bottleneck it left behind.

A few days after launch, a customer complained. "I searched for 'aifone' but got no results." I checked the database. The product name was "iPhone 15 Pro Case." The user made a simple typo, and our search system was completely blind to it.

SELECT * FROM products

WHERE name LIKE '%aifone%';

-- Result: 0 rows (database has "iPhone", not "aifone")

My first fix was naive. Just add wildcards and ignore case sensitivity, right?

SELECT * FROM products

WHERE LOWER(name) LIKE '%' || LOWER(:query) || '%';

That created a different problem. Someone searching for "case" would get every single case in the database. Galaxy cases, MacBook cases, AirPods cases. No relevance ranking. Just whatever happened to be inserted first in the database.

The bigger issue was performance. As our product catalog grew past a few thousand items, search became noticeably slower. The LIKE '%keyword%' pattern can't use indexes. We were doing full table scans on every search.

That's when I realized search is far more complex than I thought.

When I first encountered Elasticsearch, the concept of "Inverted Index" hit me like a revelation. The name itself was confusing until someone explained it with a simple metaphor.

Think about old library card catalogs. Small cards organized by title, author, and subject. Pull out the "search" subject card, and you'd find the location of every book about search. You didn't need to flip through every book. The card told you exactly where to look.

That's an inverted index.

A normal database looks like this:

Document 1: "iPhone 15 Pro Case"

Document 2: "Galaxy S24 Case"

Document 3: "iPhone Charger"

An inverted index flips it around:

"iPhone" → [Document 1, Document 3]

"15" → [Document 1]

"Pro" → [Document 1]

"Case" → [Document 1, Document 2]

"Galaxy" → [Document 2]

"S24" → [Document 2]

"Charger" → [Document 3]

When a user searches "iPhone Case," you find the intersection of documents containing "iPhone" and documents containing "Case." No need to scan every document. You just look up your pre-built index.

This is the core of search engines. Transform your data into a search-optimized structure when you store it. Like updating the card catalog while shelving books in the library.

In Elasticsearch, data is stored as JSON "Documents." A collection of documents forms an "Index." If you think in relational database terms, a document is like a row, and an index is like a table. But the reality is quite different.

// Document stored in products index

{

"id": "1",

"name": "iPhone 15 Pro Case",

"category": "Smartphone Accessories",

"price": 29000,

"description": "Clear hard case designed for iPhone 15 Pro"

}

When this document gets indexed, Elasticsearch analyzes each field. Should the name field be tokenized? Should price be treated as a number? Should category require exact matches? All these decisions happen during indexing.

Mapping defines how each field is treated. It's similar to a relational database schema but with far more options for search optimization.

{

"mappings": {

"properties": {

"name": {

"type": "text",

"analyzer": "standard",

"fields": {

"keyword": {

"type": "keyword"

}

}

},

"price": {

"type": "integer"

},

"category": {

"type": "keyword"

}

}

}

}

The text type is for full-text search. It breaks sentences into words for searching. The keyword type requires exact matches, useful for filtering and sorting.

What's interesting is you can use both on the same field. Search name for partial matches, search name.keyword for exact matches. One field, two purposes.

Analyzers determine how text gets processed. They work in three stages:

{

"settings": {

"analysis": {

"analyzer": {

"my_analyzer": {

"type": "custom",

"tokenizer": "standard",

"filter": ["lowercase", "stop"]

}

}

}

}

}

English is straightforward. Split on whitespace. "iPhone 15 Pro" becomes ["iphone", "15", "pro"]. But other languages are trickier.

Korean, for example, doesn't always use spaces. Words change form with different particles. "케이스를" (case-object), "케이스의" (case-possessive), "케이스에" (case-location). They should all match a search for "케이스" (case).

This requires morphological analysis. Korean plugins like Nori can break sentences into morphemes, removing particles and conjugations to find the root words.

If you get hundreds of search results, which one should appear first? This is where relevance scoring comes in.

Elasticsearch uses the BM25 algorithm by default. Before that, it used TF-IDF. The concepts are similar.

The TF-IDF idea:For example, searching "iPhone case":

BM25 adds document length normalization. One occurrence in a short document is weighted differently than one occurrence in a long document.

{

"query": {

"match": {

"name": {

"query": "iPhone case",

"operator": "and"

}

}

}

}

This query finds documents containing both "iPhone" and "case," sorted by BM25 score. Like a librarian recommending "I think this book is closer to what you're looking for."

Elasticsearch is powerful but heavy. It runs on the JVM, consumes significant memory, and cluster management is complex. Running it on AWS can get expensive quickly.

Depending on your project scale and needs, there are other options:

Meilisearch: Built in Rust, it's lightweight and fast. The API is intuitive, configuration is simple, and typo tolerance is built-in. For datasets in the hundreds of thousands, this might be a better fit.

Typesense: Similar to Meilisearch but written in C++. More focused on performance with excellent multi-tenant support.

Algolia: Fully managed service. Provides search UI components. Fast and convenient but expensive. Worth considering if search is core to your business and you have the budget.

PostgreSQL Full-Text Search: If you're already using PostgreSQL, you can implement search without a separate system. Using tsvector and tsquery, you can create something similar to an inverted index. For moderate scale and simple search needs, it's sufficient.

-- PostgreSQL FTS example

ALTER TABLE products

ADD COLUMN search_vector tsvector;

UPDATE products

SET search_vector = to_tsvector('english', name || ' ' || description);

CREATE INDEX idx_search ON products USING GIN(search_vector);

SELECT * FROM products

WHERE search_vector @@ to_tsquery('iPhone & case');

Introducing a search engine means your data exists in two places. PostgreSQL and Elasticsearch. How do you keep them synchronized?

Method 1: Application Layer Sync When creating, updating, or deleting products, update both the database and Elasticsearch.

async function createProduct(productData) {

// 1. Save to database

const product = await db.products.create(productData);

// 2. Index in Elasticsearch

await esClient.index({

index: 'products',

id: product.id,

document: {

name: product.name,

description: product.description,

price: product.price,

category: product.category

}

});

return product;

}

Simple, but problematic. What if the database save succeeds but Elasticsearch indexing fails? You get data inconsistency. You can't wrap them in a transaction. They're separate systems.

Method 2: Change Data Capture (CDC) Detect database changes and automatically reflect them in Elasticsearch. Tools like Debezium can read PostgreSQL's WAL (Write-Ahead Log) and send changes to Kafka. A consumer can then update Elasticsearch.

More complex but reliable. The database remains the single source of truth, and Elasticsearch simply follows.

Method 3: Scheduled Batch Sync Periodically reindex the entire database into Elasticsearch. Simplest approach, but inefficient as data grows. Real-time updates suffer too.

The lesson: there's no perfect method. Understand the trade-offs and choose what fits your situation.

What I learned building search systems:

SQL LIKE is sufficient when:Search turned out to be not just a feature but a system. Like library card catalogs, the core is organizing information for easy retrieval. Starting with LIKE queries and reaching Elasticsearch, I came to understand both the complexity and elegance of search.

We now use Meilisearch. It fits our scale perfectly. Elasticsearch is something we'll revisit later, when we truly need it.