Database Transaction: The Atomic Unit of Work

Understanding database transactions and ACID properties through practical experience

Understanding database transactions and ACID properties through practical experience

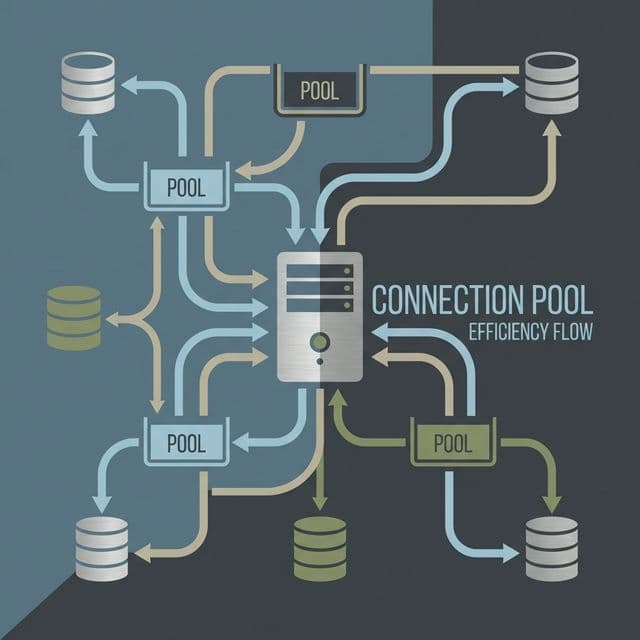

Understanding database connection pooling and performance optimization through practical experience

Understanding high availability and read performance improvement through database replication

Understanding database sharding and handling massive traffic through practical experience

Understanding vector database principles and practical applications through project experience

When running a service, you can't avoid data consistency issues. I faced this problem head-on when building my first payment system. During the process of deducting points and purchasing a product, I encountered an absurd situation: points were deducted, but the purchase failed. Customer inquiries flooded in, and I stayed up all night manually recovering data.

A senior developer asked me, "Have you tried using transactions?" I didn't even know what transactions were at that point. I thought writing SQL queries well was enough. But in production, simply executing queries wasn't sufficient. There were too many situations where multiple operations needed to be bundled together, and if something went wrong in the middle, everything had to be rolled back.

Only after properly understanding transactions did most of my service's data consistency issues get resolved. This article is a note based on that experience, covering what transactions are, why they're needed, and how to use them.

When I first encountered transactions, the most confusing part was the concept of "atomic." I remembered atoms from chemistry class and understood it meant "indivisible," but I couldn't grasp what that meant in a database context.

My code looked like this:

// Deduct points

await db.query('UPDATE users SET points = points - 1000 WHERE id = 1');

// Record purchase

await db.query('INSERT INTO purchases (user_id, product_id) VALUES (1, 100)');

The problem with this code: if the first query succeeds but the second fails, points get deducted without a purchase being recorded. Network issues, server restarts, DB connection drops—countless reasons could cause mid-process failures.

Another confusion was the concept of "isolation." I struggled to understand what happens when multiple users modify the same data simultaneously, and why strange values sometimes appeared. Especially when building an inventory system, I experienced a bug where two users simultaneously purchased the last item, and both purchases succeeded.

The decisive analogy that helped me understand transactions was "bank account transfer."

Imagine transferring 100,000 won from Account A to Account B. This process consists of two steps:

What if step 1 succeeds but step 2 fails? A's money disappears and B doesn't receive it. Money evaporates. Conversely, if only step 2 succeeds? Money is created out of thin air. Both situations are unacceptable.

A transaction is precisely the mechanism that bundles these two operations together, ensuring both succeed or both fail. When I heard this analogy, it clicked immediately. Ah, that's why it's called "atomic." It means an indivisible unit of work.

In code:

// Start transaction

await db.query('BEGIN');

try {

// Deduct from Account A

await db.query('UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100000 WHERE id = 1');

// Add to Account B

await db.query('UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100000 WHERE id = 2');

// Commit if all succeed

await db.query('COMMIT');

} catch (error) {

// Rollback if any fails

await db.query('ROLLBACK');

throw error;

}

Start a transaction with BEGIN, confirm with COMMIT if all operations succeed, and cancel all changes with ROLLBACK if an error occurs. Understanding this pattern solved numerous data consistency issues in my service.

To properly understand transactions, you need to know the four ACID properties. Initially, they felt purely theoretical, but I realized their importance as I encountered each one in production.

All operations within a transaction must be fully executed or not executed at all. The account transfer example above demonstrates atomicity.

A real case I experienced was in an order system:

BEGIN;

INSERT INTO orders (user_id, total) VALUES (1, 50000);

UPDATE products SET stock = stock - 1 WHERE id = 100;

INSERT INTO order_items (order_id, product_id) VALUES (LAST_INSERT_ID(), 100);

COMMIT;

These three queries form one logical operation: create order, deduct stock, record order details. If any fails, all must be canceled. Without atomicity, you get situations like orders created with unchanged stock, or stock deducted without order records.

After a transaction completes, all database constraints and rules must be maintained.

For example, if there's a constraint that account balance cannot be negative:

-- This transaction should fail

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100000 WHERE id = 1;

-- If balance was 50000? It shouldn't become -50000

ROLLBACK; -- Automatically rolled back or blocked by CHECK constraint

In my case, adding a CHECK (points >= 0) constraint to the points system automatically blocked attempts to deduct points when insufficient. Thanks to consistency, data always maintained a state satisfying business rules.

This was the most complex part and created the most bugs in production.

This situation occurred in my ticket booking system:

// Users A and B simultaneously try to book the last ticket

// User A

const ticket = await db.query('SELECT remaining FROM tickets WHERE id = 1');

// remaining = 1

// User B (almost simultaneously)

const ticket = await db.query('SELECT remaining FROM tickets WHERE id = 1');

// remaining = 1 (A hasn't updated yet)

// User A

await db.query('UPDATE tickets SET remaining = 0 WHERE id = 1');

// User B

await db.query('UPDATE tickets SET remaining = 0 WHERE id = 1');

// Both succeed! 2 tickets sold

To solve this, you need to adjust the isolation level or use pessimistic locking:

BEGIN;

SELECT remaining FROM tickets WHERE id = 1 FOR UPDATE; -- Lock the row

-- Other transactions can't read this row

UPDATE tickets SET remaining = remaining - 1 WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;

Using FOR UPDATE locks the row, forcing other transactions to wait until this one completes. This solved the concurrency issue.

Once a transaction successfully commits, its results must persist even if the system crashes.

This is mostly handled by the database, so developers rarely need to worry about it directly. However, once when the server suddenly restarted, transactions just before commit disappeared. It turned out fsync was disabled in the DB configuration, so data in memory was lost before being written to disk.

To ensure durability, the DB must use mechanisms like WAL (Write-Ahead Logging) to guarantee disk writes at commit time.

Perfect isolation guarantees hurt performance. If all transactions execute sequentially, concurrency becomes zero. So in production, you must choose an appropriate isolation level for the situation.

The lowest isolation level. Can read uncommitted data. Dirty reads occur.

-- Transaction A

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = 1000000 WHERE id = 1;

-- Not committed yet

-- Transaction B (simultaneously)

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 1;

-- Reads 1000000 (uncommitted data!)

-- Transaction A

ROLLBACK; -- Canceled

-- Transaction B read non-existent data

I rarely use this level in production. Data consistency is too risky.

Can only read committed data. Prevents dirty reads but non-repeatable reads can occur.

-- Transaction A

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 1;

-- 100000

-- Transaction B (simultaneously)

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = 200000 WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;

-- Transaction A (read again)

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 1;

-- 200000 (value changed!)

Reading the same data twice in the same transaction yields different values. Usually fine, but can be problematic when generating statistics or reports.

Reading the same data in the same transaction always returns the same value. However, phantom reads can occur.

-- Transaction A

BEGIN;

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM orders WHERE user_id = 1;

-- 10

-- Transaction B

INSERT INTO orders (user_id, total) VALUES (1, 50000);

COMMIT;

-- Transaction A

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM orders WHERE user_id = 1;

-- 11 (new row added!)

Existing row values don't change, but new rows can be added or deleted. I use this level for most of my services.

The highest isolation level. Transactions behave as if executing completely sequentially. All problems solved, but performance drops significantly.

Only use for cases where data consistency is absolutely critical, like financial systems. I only applied this level to core payment logic.

Since most people use ORMs nowadays, knowing how to use transactions in ORMs is important.

Prisma example:await prisma.$transaction(async (tx) => {

// Deduct points

await tx.user.update({

where: { id: userId },

data: { points: { decrement: 1000 } }

});

// Record purchase

await tx.purchase.create({

data: {

userId: userId,

productId: productId,

amount: 1000

}

});

});

All operations inside $transaction are bundled into one transaction. Errors trigger automatic rollback.

const t = await sequelize.transaction();

try {

await User.update(

{ points: sequelize.literal('points - 1000') },

{ where: { id: userId }, transaction: t }

);

await Purchase.create({

userId: userId,

productId: productId

}, { transaction: t });

await t.commit();

} catch (error) {

await t.rollback();

throw error;

}

Transactions cause DB locks, so minimize their scope.

❌ Bad:

await prisma.$transaction(async (tx) => {

const user = await tx.user.findUnique({ where: { id: userId } });

// External API call (slow!)

const paymentResult = await externalPaymentAPI.charge(user.cardToken, 1000);

await tx.purchase.create({ data: { userId, amount: 1000 } });

});

Slow external API calls keep the transaction open, blocking other requests.

✅ Good:

// External API call outside transaction

const paymentResult = await externalPaymentAPI.charge(cardToken, 1000);

// If successful, quickly process DB in transaction

await prisma.$transaction(async (tx) => {

await tx.purchase.create({ data: { userId, amount: 1000 } });

await tx.user.update({

where: { id: userId },

data: { points: { increment: 100 } }

});

});

When multiple transactions wait for each other's locks, deadlocks occur.

// Transaction A

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100 WHERE id = 1; -- Lock 1

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100 WHERE id = 2; -- Wait for lock 2

// Transaction B (simultaneously)

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 50 WHERE id = 2; -- Lock 2

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 50 WHERE id = 1; -- Wait for lock 1

-- Deadlock: waiting for each other!

Solution: always acquire locks in the same order:

// Always acquire lock starting with smaller id

const [smallerId, largerId] = [id1, id2].sort();

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100 WHERE id = smallerId;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100 WHERE id = largerId;

COMMIT;

The most critical part. Payments must never fail.

async function processPayment(userId: number, amount: number) {

return await prisma.$transaction(async (tx) => {

// 1. Check and deduct user points

const user = await tx.user.update({

where: { id: userId },

data: { points: { decrement: amount } }

});

if (user.points < 0) {

throw new Error('Insufficient points');

}

// 2. Create payment record

const payment = await tx.payment.create({

data: {

userId: userId,

amount: amount,

status: 'COMPLETED'

}

});

// 3. Create purchase history

await tx.purchase.create({

data: {

userId: userId,

paymentId: payment.id,

productId: productId

}

});

return payment;

}, {

isolationLevel: 'Serializable' // Highest isolation

});

}

Where concurrency issues occur most frequently.

async function purchaseProduct(productId: number, quantity: number) {

return await prisma.$transaction(async (tx) => {

// Check stock with pessimistic lock

const product = await tx.$queryRaw`

SELECT * FROM products

WHERE id = ${productId}

FOR UPDATE

`;

if (product.stock < quantity) {

throw new Error('Out of stock');

}

// Deduct stock

await tx.product.update({

where: { id: productId },

data: { stock: { decrement: quantity } }

});

return product;

});

}

When processing large amounts of data, split transactions into smaller chunks.

// ❌ Bad: 100k records in one transaction

await prisma.$transaction(async (tx) => {

for (const user of allUsers) { // 100k users

await tx.user.update({ where: { id: user.id }, data: { ... } });

}

});

// ✅ Good: Process in batches of 1000

for (let i = 0; i < allUsers.length; i += 1000) {

const batch = allUsers.slice(i, i + 1000);

await prisma.$transaction(async (tx) => {

for (const user of batch) {

await tx.user.update({ where: { id: user.id }, data: { ... } });

}

});

}

Transactions are a mechanism that bundles multiple DB operations into one atomic unit, ensuring all succeed or all fail. Understanding ACID properties, choosing appropriate isolation levels, and minimizing transaction scope solves most data consistency problems. When handling critical data like payments, inventory, and points in production, you must use transactions.