SQL vs NoSQL: 데이터베이스 전쟁의 승자는? (완벽 가이드)

RDBMS와 NoSQL의 아키텍처(B-Tree vs LSM), CAP 이론, ACID 트랜잭션 격리 수준, 그리고 샤딩 전략과 NewSQL까지.

RDBMS와 NoSQL의 아키텍처(B-Tree vs LSM), CAP 이론, ACID 트랜잭션 격리 수준, 그리고 샤딩 전략과 NewSQL까지.

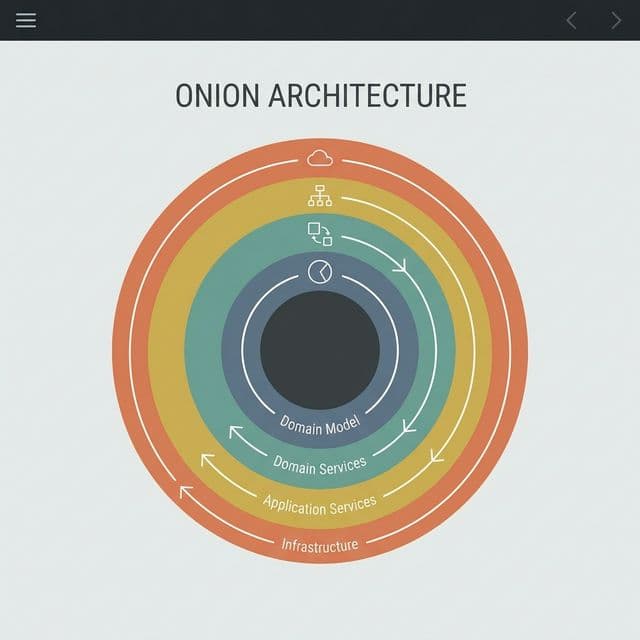

로버트 C. 마틴(Uncle Bob)이 제안한 클린 아키텍처의 핵심은 무엇일까요? 양파 껍질 같은 계층 구조와 의존성 규칙(Dependency Rule)을 통해 프레임워크와 UI로부터 독립적인 소프트웨어를 만드는 방법을 정리합니다.

DB 설계의 기초. 데이터를 쪼개고 쪼개서 이상 현상(Anomaly)을 방지하는 과정. 제1, 2, 3 정규형을 쉽게 설명합니다.

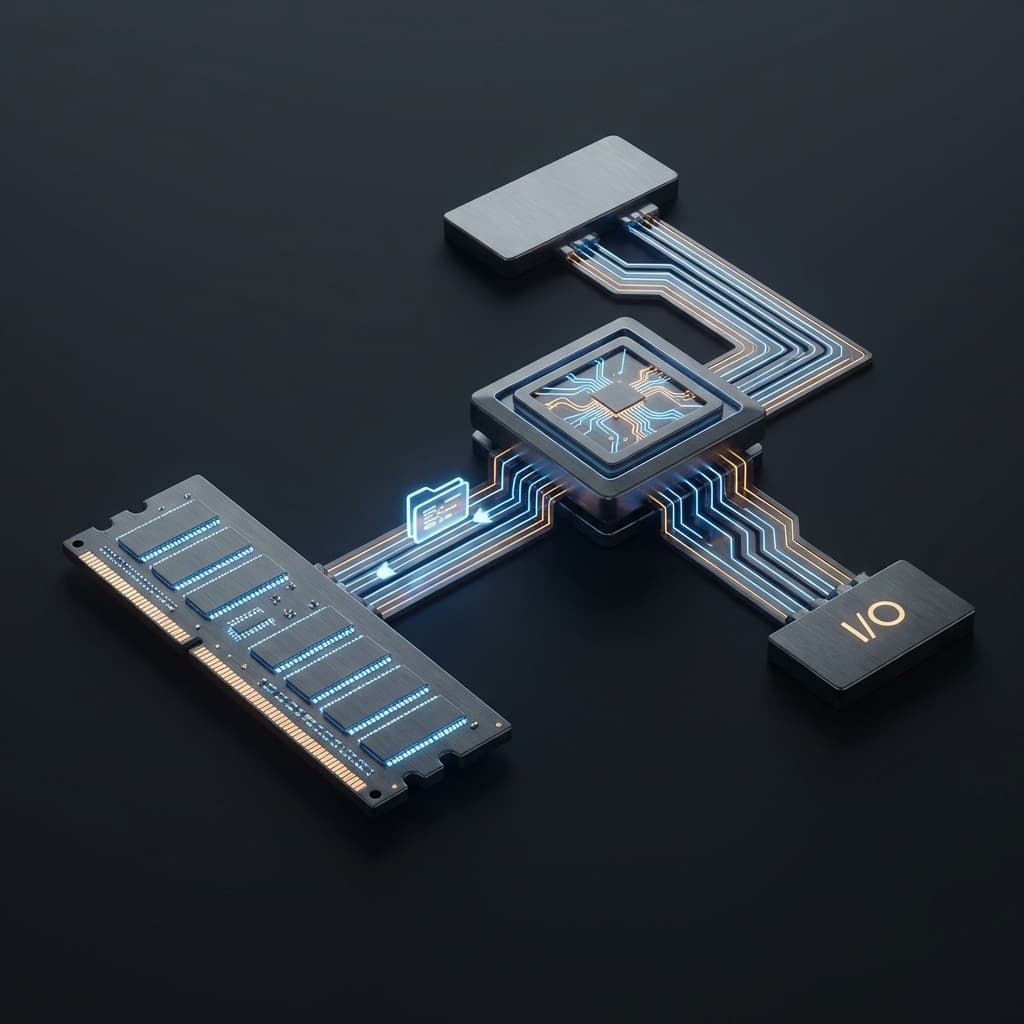

왜 CPU는 빠른데 컴퓨터는 느릴까? 80년 전 고안된 폰 노이만 구조의 혁명적인 아이디어와, 그것이 남긴 치명적인 병목현상에 대해 정리했습니다.

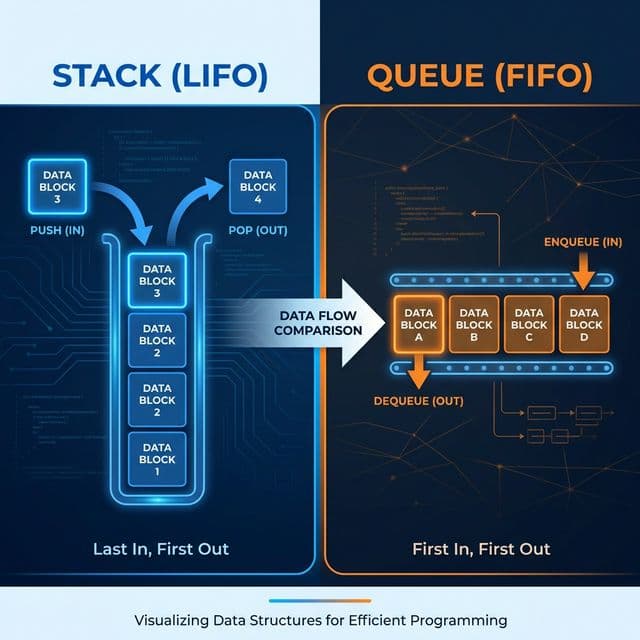

프링글스 통(Stack)과 맛집 대기 줄(Queue). 가장 기초적인 자료구조지만, 이걸 모르면 재귀 함수도 메시지 큐도 이해할 수 없습니다.

첫 프로젝트에서 나는 아무 생각 없이 MySQL을 골랐다. 왜냐고? 모두가 쓰니까. 튜토리얼에 나오니까. 설치가 쉬우니까. 그런데 막상 서비스를 운영하면서 이상한 질문들이 쌓이기 시작했다. "왜 인스타그램은 PostgreSQL을 쓰지?", "왜 트위터는 Cassandra로 갈아탔지?", "왜 넷플릭스는 MySQL, Redis, Cassandra를 전부 섞어서 쓰지?"

그때 나는 데이터베이스를 "그냥 데이터 저장하는 곳" 정도로만 생각했다. 하지만 데이터베이스는 단순히 데이터를 저장하는 게 아니었다. 아키텍처의 심장이었다. 데이터베이스 선택은 시스템의 확장성, 안정성, 성능, 개발 속도, 심지어 비용까지 결정한다. 코드는 바뀌어도 데이터는 영원하기 때문에, 잘못된 데이터베이스 선택은 나중에 뒤집기가 거의 불가능하다.

이 글은 내가 3년간 삽질하면서 정리한 "SQL vs NoSQL 완벽 가이드"다. 단순한 비교표가 아니라, 내부 구현 원리(B+ Tree vs LSM Tree), 분산 시스템 이론(CAP/PACELC), 트랜잭션 격리 수준, 샤딩 전략까지 전부 담았다. 이 글을 다 읽고 나면, "우리 서비스에는 이 데이터베이스가 필요하다"고 자신 있게 말할 수 있을 것이다.

처음에 나는 SQL이 느리다고 생각했다. NoSQL이 "더 빠른 최신 기술"이라고 착각했다. 그런데 이건 완전히 틀렸다. SQL이 느린 게 아니라, SQL은 다른 것을 최적화한 것이었다. 속도가 아니라 정확성(Correctness)과 무결성(Integrity)을 최적화했다.

개발자는 그냥 BEGIN → UPDATE → COMMIT만 치면 된다. 하지만 데이터베이스 내부에서는 엄청난 일이 일어난다.

트랜잭션이 중간에 실패하면? 데이터베이스는 Undo Log를 사용해서 역순으로 되돌린다. 예를 들어, 계좌 A에서 10만 원을 빼고, 계좌 B에 10만 원을 더하는 중간에 에러가 나면, Undo Log를 보고 A 계좌를 복구한다.

-- 트랜잭션 시작

BEGIN;

-- 계좌 A에서 출금

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100000 WHERE id = 'A';

-- (내부적으로 Undo Log 기록: "A의 잔액은 원래 500000이었다")

-- 계좌 B에 입금 (여기서 에러 발생!)

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100000 WHERE id = 'B';

-- 에러! DB가 죽음!

-- DB 재시작 후: Undo Log를 읽고, A 계좌 복구

ROLLBACK;

이게 바로 "은행 시스템에는 SQL이 필수"라는 이유다. 돈이 사라지거나 두 배로 생기면 안 되니까.

데이터베이스가 COMMIT을 승인했는데, 갑자기 정전이 나면? 데이터는 안전할까? 놀랍게도 안전하다. 왜냐하면 데이터베이스는 실제 데이터 파일에 쓰기 전에, WAL(Write Ahead Log)이라는 로그 파일에 먼저 기록하기 때문이다.

1. 트랜잭션: UPDATE users SET name = 'Kim' WHERE id = 1;

2. DB 내부 순서:

a. WAL에 먼저 기록: "id=1의 name을 Kim으로 변경" (디스크에 flush)

b. COMMIT 승인 반환

c. 나중에 실제 데이터 파일(.ibd)에 반영 (Background)

3. 만약 (c) 단계에서 정전?

→ 재시작 후, WAL을 읽고 복구 (Crash Recovery)

이게 와닿았던 순간은, 내가 운영하던 서버가 EC2 인스턴스가 갑자기 죽었을 때였다. 재시작 후 로그를 보니 InnoDB: Applying log... 이런 메시지가 떴다. MySQL이 WAL을 읽고 자동으로 복구하고 있던 것이었다. 그 순간 "아, ACID는 그냥 이론이 아니라 진짜 구현된 거구나"를 체감했다.

여러 사용자가 동시에 데이터를 읽고 쓸 때, 어떻게 충돌을 방지할까? 초보 때의 나는 "Lock을 걸면 되지 않나?"라고 생각했다. 하지만 Lock만 쓰면 성능이 엄청 느려진다. 그래서 SQL 데이터베이스는 MVCC(Multi-Version Concurrency Control)을 쓴다.

-- 트랜잭션 A (시간 T1에 시작)

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 'A';

-- 결과: 100만원

-- 트랜잭션 B (시간 T2에 시작)

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = 50만원 WHERE id = 'A';

COMMIT; -- B는 이미 끝남

-- 트랜잭션 A (다시 읽음)

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 'A';

-- MySQL (Repeatable Read 격리 수준): 여전히 100만원!

-- PostgreSQL (Read Committed): 50만원!

MVCC는 데이터의 여러 버전을 유지한다. 트랜잭션 A가 시작했을 때의 "스냅샷"을 보관해서, 다른 트랜잭션이 데이터를 바꿔도 A는 여전히 예전 버전을 읽을 수 있다. 이게 바로 "격리(Isolation)"의 핵심이다.

내가 이걸 처음 제대로 이해한 건, 재고 관리 시스템에서 동시 주문 처리 버그를 디버깅할 때였다. 두 명의 유저가 "마지막 1개" 상품을 동시에 주문했는데, 둘 다 성공해버린 것이다. 문제는 Isolation Level이 Read Uncommitted로 설정되어 있어서, 한 트랜잭션이 아직 커밋 안 한 데이터를 다른 트랜잭션이 읽어버린 것이었다. Repeatable Read로 바꾸니 해결됐다.

SQL과 NoSQL의 성능 차이는 "프로그래밍 언어 차이"가 아니라 스토리지 엔진의 차이에서 나온다. 결국 이거였다.

RDBMS(MySQL, PostgreSQL)는 거의 대부분 B+ Tree를 사용한다. B+ Tree는 "균형 잡힌 트리"로, 검색 시간이 O(log N)이다.

B+ Tree 구조 (M=4 차수 예시):

[10, 20, 30]

/ | | \

[1,5] [11,15] [21,25] [31,35]

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

[Data] [Data] [Data] [Data]

(Linked List로 연결 → 범위 검색 빠름!)

SELECT * FROM orders

WHERE created_at BETWEEN '2025-01-01' AND '2025-01-31';

이런 쿼리는 B+ Tree의 리프 노드가 Linked List로 연결되어 있어서, 첫 번째 데이터를 찾으면 그 다음부터는 순차적으로 쭉 읽으면 된다. 디스크 I/O가 최소화된다.

단점: 쓰기가 느리다 (트리 재조정 오버헤드)데이터를 삽입하면, 트리의 균형을 유지하기 위해 노드를 분할(Split)하거나 병합(Merge)해야 한다. 이게 Random I/O를 발생시킨다. 디스크는 Sequential I/O는 빠른데, Random I/O는 느리다. (SSD도 마찬가지)

대량의 쓰기가 발생하는 환경, 예를 들어 실시간 로그 저장 같은 경우, MySQL 같은 B+ Tree 기반 DB는 이 Random Write 부하를 버티지 못하고 쿼리가 쌓이기 시작한다는 사례를 접했다. B+ Tree가 매번 Random Write를 하는 구조적 특성 때문이다.

NoSQL(Cassandra, MongoDB, RocksDB)은 대부분 LSM Tree(Log-Structured Merge Tree)를 사용한다. 이건 "쓰기 최적화" 구조다.

LSM Tree 구조:

1. MemTable (메모리): 데이터를 일단 메모리에 씀 (RAM 속도!)

→ 데이터: [key3=value3, key1=value1, key5=value5]

2. MemTable이 꽉 차면, Disk에 SSTable로 Flush

→ SSTable_1.db (정렬되어 있음, Immutable)

→ SSTable_2.db (새로 추가된 데이터)

3. 읽기: MemTable → SSTable_1 → SSTable_2 순서로 검색

→ 최신 데이터가 우선 (업데이트는 "새 값을 추가"하는 것)

4. Compaction: 주기적으로 SSTable들을 합침 (Background)

→ SSTable_1 + SSTable_2 → SSTable_merged.db

모든 쓰기가 Sequential Write다. 디스크는 Sequential Write가 Random Write보다 100배 이상 빠르다. 그래서 초당 수십만 건의 쓰기를 처리할 수 있다.

단점: 읽기가 느리다 (Write Amplification)하나의 데이터를 읽으려면, MemTable → SSTable_1 → SSTable_2 → ... 이렇게 여러 파일을 뒤져야 한다. 그래서 Bloom Filter (확률적 자료구조)를 써서, "이 SSTable에 데이터가 없을 확률 99%"라고 판단하면 스킵한다.

# Bloom Filter 예시 (Python)

from bloom_filter2 import BloomFilter

# SSTable마다 Bloom Filter 생성

bloom = BloomFilter(max_elements=10000)

bloom.add("user_12345")

# 읽기 최적화

if "user_99999" not in bloom:

# 이 SSTable은 스킵! (99% 확률로 없음)

pass

높은 쓰기 처리량이 필요한 경우, MySQL 대신 Cassandra(LSM Tree)로 전환하면 대량 쓰기를 훨씬 잘 소화한다고 한다. 대신 읽기 쿼리는 확실히 MySQL보다 느리다. 하지만 로그처럼 쓰기가 압도적으로 많은 경우라면 그 트레이드오프를 감수할 수 있다.

NoSQL을 공부하면서 가장 혼란스러웠던 게 CAP 이론이었다. 처음엔 "3개 중 2개를 선택한다"는 게 무슨 뜻인지 전혀 와닿지 않았다.

문제는, P(Partition)는 선택 사항이 아니라 필수라는 것이다. 네트워크는 항상 불안정하다. AWS 리전 간 통신도 끊길 수 있다. 그래서 실질적으로는 CP(일관성 우선)냐 AP(가용성 우선)냐를 선택해야 한다.

MongoDB는 "일관성"을 선택했다. 네트워크 분할이 발생하면, Primary 노드만 쓰기를 받고, 나머지는 읽기 전용으로 바뀐다.

// MongoDB 예시: 네트워크 분할 시나리오

// 서울 리전과 도쿄 리전 간 네트워크 단절

// 서울 Primary 노드

db.users.insertOne({ name: "Kim" }); // 성공

// 도쿄 Secondary 노드

db.users.insertOne({ name: "Lee" }); // 실패! "not primary" 에러

db.users.find(); // 읽기는 가능 (단, 약간 오래된 데이터일 수 있음)

MongoDB는 "쓰기는 무조건 Primary에만"이라는 원칙으로 일관성을 보장한다. 대신, Primary가 죽으면 Failover(다른 노드가 Primary로 승격)가 일어나기 전까지 쓰기가 불가능하다.

Cassandra는 "가용성"을 선택했다. 네트워크가 끊겨도, 각 리전이 독립적으로 쓰기를 받는다.

-- Cassandra 예시: 네트워크 분할 시나리오

-- 서울 리전

INSERT INTO users (id, name) VALUES (1, 'Kim'); -- 성공

-- 도쿄 리전 (네트워크 단절 상태)

INSERT INTO users (id, name) VALUES (1, 'Lee'); -- 성공!

-- 나중에 네트워크 복구되면?

-- Cassandra는 "Last Write Wins" (마지막 쓰기가 이김) 정책으로 충돌 해결

-- 결과: id=1의 이름은 'Lee' (타임스탬프가 더 최신)

Cassandra는 항상 응답한다. 대신, 일시적으로 데이터가 불일치할 수 있다. 이게 Eventual Consistency(최종적 일관성)다.

CAP 이론이 와닿은 건 실제 장애 사례를 읽으면서였다. 어떤 글로벌 서비스에서 서울-도쿄 간 네트워크가 잠깐 끊겼는데, MongoDB는 도쿄에서 쓰기 에러가 났고, Cassandra는 멀쩡히 동작했다고 한다. 대신 나중에 보니 같은 데이터가 두 리전에서 다르게 나왔다는 것이다. 그때 깨달았다. "CAP는 이론이 아니라 실제 선택의 문제구나."

CAP 이론은 "네트워크 분할 시"에만 해당한다. 그럼 네트워크가 정상일 때는? 그때도 trade-off가 있다. 바로 PACELC 이론이다.

예를 들어, MongoDB는 "PC/EC" 시스템이다. 분할 시에도 일관성(C), 정상 시에도 일관성(C) 우선이라 Latency가 약간 느릴 수 있다. 반대로 Cassandra는 "PA/EL" 시스템이다. 가용성(A) 우선이고, Latency(L)도 우선이라 빠르지만 일관성이 약하다.

데이터가 수십 테라바이트가 넘어가면? 한 서버에 못 담는다. 그럼 쪼개야 한다. 이게 샤딩(Sharding)이다.

샤딩을 이해하는 최고의 비유는 "이삿짐 센터"다.

문제는, 트럭을 나누면 "짐을 어느 트럭에 실을지" 결정해야 한다는 것이다. 이게 바로 샤딩 전략이다.

유저 ID를 해시한 값으로 샤드를 결정한다.

# 샤드 결정 공식

shard_id = hash(user_id) % 4 # 4대 서버

# 예시

hash("user_12345") % 4 = 2 → Shard 2에 저장

hash("user_99999") % 4 = 1 → Shard 1에 저장

장점: 데이터가 균등하게 분산된다.

단점: 서버를 추가하면? 예를 들어 4대 → 5대로 늘리면, 공식이 % 4에서 % 5로 바뀐다. 그럼 기존 데이터의 80%가 다른 샤드로 이동해야 한다. 이게 Resharding 문제다.

해결책: Consistent Hashing (일관된 해싱). 서버를 "링(Ring)" 구조로 배치해서, 서버를 추가해도 일부 데이터만 이동하게 한다.

# Consistent Hashing 예시

ring = [Shard_1: 0°, Shard_2: 90°, Shard_3: 180°, Shard_4: 270°]

hash("user_12345") = 120° → Shard_3에 저장 (120° 이후 첫 번째 샤드)

# Shard_5를 45°에 추가하면?

→ 0° ~ 45° 구간의 데이터만 Shard_5로 이동 (전체의 12.5%만!)

ID 범위로 샤드를 나눈다.

Shard 1: user_id 1 ~ 1,000,000

Shard 2: user_id 1,000,001 ~ 2,000,000

Shard 3: user_id 2,000,001 ~ 3,000,000

장점: 범위 검색이 빠르다. WHERE user_id BETWEEN 1 AND 10000 같은 쿼리는 Shard 1에만 가면 된다.

단점: Hotspot 문제. 예를 들어, 최근 가입한 유저(3,000,000번대)만 활동이 많으면 Shard 3만 과부하가 걸린다.

내가 이 문제를 겪은 건, 게시글 ID를 기준으로 Range Sharding을 했을 때였다. 최신 게시글(높은 ID)만 조회가 많아서, 마지막 샤드만 CPU 100%가 걸렸다. 결국 Hash Sharding으로 바꿔서 해결했다.

이론만으로는 부족하다. 실제 코드로 차이를 체감해보자.

-- Users 테이블

CREATE TABLE users (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(50)

);

-- Orders 테이블

CREATE TABLE orders (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

user_id INT,

product VARCHAR(50),

FOREIGN KEY (user_id) REFERENCES users(id)

);

-- 유저와 주문 조회 (JOIN 필요)

SELECT u.name, o.product

FROM users u

JOIN orders o ON u.id = o.user_id

WHERE u.id = 123;

장점: 데이터 중복이 없다 (정규화). 유저 이름을 바꾸면 한 곳만 수정하면 된다.

단점: JOIN은 느리다. 두 테이블을 스캔해서 매칭해야 하니까. (최악의 경우 O(N*M))

// MongoDB: 한 Document에 전부 포함

{

"_id": 123,

"name": "Kim",

"orders": [

{ "product": "iPhone", "price": 1000000 },

{ "product": "MacBook", "price": 2000000 }

]

}

// 유저와 주문 조회 (JOIN 없이 한 번에!)

db.users.findOne({ "_id": 123 });

장점: JOIN이 없어서 빠르다. 읽기가 단순하다.

단점: 데이터 중복. 같은 상품이 여러 유저의 주문에 포함되면, 상품 정보가 중복된다. 상품 가격을 바꾸려면 모든 Document를 업데이트해야 한다.

언제 SQL을 쓰고, 언제 MongoDB를 쓸까?

데이터베이스 성능을 극대화하려면, 캐시(Cache)를 써야 한다. 가장 많이 쓰는 게 Redis다.

# 캐시 조회 → DB 조회 → 캐시 저장

import redis

r = redis.Redis()

def get_user(user_id):

# 1. 캐시부터 확인

cached = r.get(f"user:{user_id}")

if cached:

return cached # 캐시 히트!

# 2. 캐시 미스 → DB 조회

user = db.query(f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = {user_id}")

# 3. 캐시에 저장 (TTL 1시간)

r.setex(f"user:{user_id}", 3600, user)

return user

장점: 캐시가 비어있어도 동작한다. 필요할 때만 캐시에 저장한다.

단점: 캐시 미스 시 Latency가 늘어난다. (Cache + DB 두 번 조회)

# 쓰기할 때 캐시와 DB를 동시에 업데이트

def update_user(user_id, name):

# 1. DB 업데이트

db.execute(f"UPDATE users SET name = '{name}' WHERE id = {user_id}")

# 2. 캐시도 업데이트

r.set(f"user:{user_id}", name)

장점: 캐시와 DB가 항상 동기화된다.

단점: 쓰기 성능이 느려진다. (두 번 쓰기)

내가 캐싱을 처음 제대로 활용한 건, API 응답 속도를 줄일 때였다. DB 쿼리가 500ms 걸렸는데, Redis 캐시를 추가하니 5ms로 줄었다. 100배 개선이었다. 그 순간 "캐시는 선택이 아니라 필수구나"를 받아들였다.

결국, 내가 3년 동안 삽질하면서 내린 결론은 이거였다. "하나의 데이터베이스로는 부족하다."

현대의 서비스는 Polyglot Persistence(다중 데이터베이스 전략)를 쓴다.

각각의 도구를 적재적소에 쓰는 게 진짜 "아키텍처"다.

내가 처음 프로젝트에서 "MySQL 하나로 다 하려고" 했던 건, 마치 "망치 하나로 모든 공사를 하려는 것"과 같았다. 못은 망치로 박지만, 나사는 드라이버로 돌려야 한다. 데이터베이스도 마찬가지다.

이 글을 읽은 당신은 이제, "우리 서비스에는 이 데이터베이스가 필요하다"고 자신 있게 말할 수 있을 것이다. 그리고 실무에서 "CAP 이론이 뭔가요?"라는 질문에, "실제로는 CP냐 AP냐를 선택하는 문제입니다"라고 대답할 수 있을 것이다.

On my first real project, I picked MySQL without thinking. Why? Because everyone uses it. Because tutorials use it. Because it's easy to install. But as I started running the service in production, weird questions started piling up. "Why does Instagram use PostgreSQL?", "Why did Twitter migrate to Cassandra?", "Why does Netflix use MySQL, Redis, AND Cassandra all at the same time?"

Back then, I thought databases were just "a place to store data." But I was completely wrong. Databases are the heart of your architecture. Your database choice determines your system's scalability, reliability, performance, development speed, and even cost. Code can change, but data is forever. A wrong database choice is nearly impossible to reverse later.

This article is my "SQL vs NoSQL Complete Guide" that I assembled after 3 years of painful trial and error. It's not just a comparison table. It covers internal implementation details (B+ Tree vs LSM Tree), distributed systems theory (CAP/PACELC), transaction isolation levels, and sharding strategies. After reading this, you'll be able to confidently say "Our service needs THIS database."

When I started, I thought SQL was slow. I thought NoSQL was the "faster, modern technology." But I was completely wrong. SQL isn't slow. SQL is optimized for different things. Not for speed, but for correctness and integrity.

As a developer, you just type BEGIN → UPDATE → COMMIT. But inside the database, incredible engineering happens.

What happens if a transaction fails halfway through? The database uses an Undo Log to reverse changes in reverse order. For example, if you subtract $1000 from Account A and add $1000 to Account B, and an error occurs in the middle, the Undo Log restores Account A.

-- Start transaction

BEGIN;

-- Withdraw from Account A

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 1000 WHERE id = 'A';

-- (Internally records Undo Log: "A's balance was originally 5000")

-- Deposit to Account B (Error happens here!)

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 1000 WHERE id = 'B';

-- Error! DB crashes!

-- After DB restart: Read Undo Log and restore Account A

ROLLBACK;

This is exactly why "banking systems require SQL." Money can't disappear or double.

What if the database approves a COMMIT, but then there's a sudden power outage? Is the data safe? Surprisingly, yes. Because before writing to the actual data files, the database writes to the WAL (Write Ahead Log) first.

1. Transaction: UPDATE users SET name = 'Kim' WHERE id = 1;

2. Internal DB sequence:

a. Write to WAL first: "Change name of id=1 to Kim" (flush to disk)

b. Return COMMIT approval

c. Later reflect in actual data file (.ibd) (Background)

3. If power outage happens at step (c)?

→ After restart, read WAL and recover (Crash Recovery)

I truly understood this when my EC2 instance suddenly died. After restart, I saw logs like InnoDB: Applying log.... MySQL was automatically recovering using the WAL. That moment, I realized "Oh, ACID isn't just theory. It's actually implemented."

When multiple users read and write data simultaneously, how do you prevent conflicts? Beginner me thought "Just use locks, right?" But if you only use locks, performance becomes terrible. That's why SQL databases use MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control).

-- Transaction A (starts at time T1)

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 'A';

-- Result: $10,000

-- Transaction B (starts at time T2)

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = 5000 WHERE id = 'A';

COMMIT; -- B is already done

-- Transaction A (reads again)

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 'A';

-- MySQL (Repeatable Read isolation): Still $10,000!

-- PostgreSQL (Read Committed): $5,000!

MVCC maintains multiple versions of data. It keeps a "snapshot" from when Transaction A started, so even if other transactions change the data, A still reads the old version. This is the core of "Isolation."

I first truly understood this when debugging a concurrent order bug in an inventory system. Two users ordered "the last 1 item" simultaneously, and both succeeded. The problem was the Isolation Level was set to Read Uncommitted, so one transaction read uncommitted data from another transaction. Changing to Repeatable Read fixed it.

The performance difference between SQL and NoSQL doesn't come from "programming language differences" but from storage engine differences. This was the key insight.

RDBMS (MySQL, PostgreSQL) almost always use B+ Tree. B+ Tree is a "balanced tree" with search time of O(log N).

B+ Tree structure (M=4 example):

[10, 20, 30]

/ | | \

[1,5] [11,15] [21,25] [31,35]

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

[Data] [Data] [Data] [Data]

(Connected via Linked List → Fast range queries!)

SELECT * FROM orders

WHERE created_at BETWEEN '2025-01-01' AND '2025-01-31';

These queries are fast because B+ Tree's leaf nodes are connected via Linked List. Once you find the first data point, you just read sequentially. Disk I/O is minimized.

Disadvantage: Writes are slow (tree rebalancing overhead)When inserting data, the tree needs to split or merge nodes to maintain balance. This causes Random I/O. Disks are fast at Sequential I/O but slow at Random I/O. (Even SSDs!)

In environments with heavy write loads — like real-time log storage — there are well-known cases where B+ Tree-based databases like MySQL struggle to keep up. Queries pile up because B+ Tree performs Random Writes on every insert, which is structurally expensive.

NoSQL (Cassandra, MongoDB, RocksDB) mostly use LSM Tree (Log-Structured Merge Tree). This is a "write-optimized" structure.

LSM Tree structure:

1. MemTable (memory): Write data to memory first (RAM speed!)

→ Data: [key3=value3, key1=value1, key5=value5]

2. When MemTable fills, flush to disk as SSTable

→ SSTable_1.db (sorted, immutable)

→ SSTable_2.db (newly added data)

3. Read: Search MemTable → SSTable_1 → SSTable_2 in order

→ Latest data wins (update = "add new value")

4. Compaction: Periodically merge SSTables (Background)

→ SSTable_1 + SSTable_2 → SSTable_merged.db

All writes are Sequential Writes. Disks are 100x faster at Sequential Write than Random Write. That's why LSM can handle hundreds of thousands of writes per second.

Disadvantage: Reads are slower (Write Amplification)To read a single piece of data, you need to search MemTable → SSTable_1 → SSTable_2 → ... across multiple files. That's why they use Bloom Filters (probabilistic data structure) to skip SSTables with 99% probability of not containing the data.

# Bloom Filter example (Python)

from bloom_filter2 import BloomFilter

# Create Bloom Filter for each SSTable

bloom = BloomFilter(max_elements=10000)

bloom.add("user_12345")

# Read optimization

if "user_99999" not in bloom:

# Skip this SSTable! (99% probability it doesn't exist)

pass

When high write throughput is the bottleneck, switching from MySQL to Cassandra (LSM Tree) is a common approach — and reportedly handles massive write volumes far more efficiently. Read queries are definitely slower than MySQL. But for write-heavy workloads like logs, that trade-off is often acceptable.

The most confusing concept when studying NoSQL was CAP Theorem. At first, I didn't understand what "choose 2 out of 3" meant.

The problem is, P (Partition) is not optional—it's mandatory. Networks are always unreliable. Even AWS inter-region communication can break. So in practice, you must choose between CP (Consistency priority) or AP (Availability priority).

MongoDB chose "consistency." When network partition occurs, only the Primary node accepts writes, and others become read-only.

// MongoDB example: Network partition scenario

// Network disconnected between Seoul region and Tokyo region

// Seoul Primary node

db.users.insertOne({ name: "Kim" }); // Success

// Tokyo Secondary node

db.users.insertOne({ name: "Lee" }); // Fail! "not primary" error

db.users.find(); // Read works (but might be slightly stale data)

MongoDB guarantees consistency with the principle "writes only to Primary." However, if Primary dies, writes are impossible until Failover (another node becomes Primary) happens.

Cassandra chose "availability." Even when network is partitioned, each region independently accepts writes.

-- Cassandra example: Network partition scenario

-- Seoul region

INSERT INTO users (id, name) VALUES (1, 'Kim'); -- Success

-- Tokyo region (network disconnected)

INSERT INTO users (id, name) VALUES (1, 'Lee'); -- Success!

-- When network recovers later?

-- Cassandra resolves conflict with "Last Write Wins" policy

-- Result: id=1's name is 'Lee' (more recent timestamp)

Cassandra always responds. However, data might be temporarily inconsistent. This is Eventual Consistency.

CAP Theorem truly clicked when I read about a real-world incident. A global service had its Seoul-Tokyo network briefly disconnected. MongoDB had write errors in Tokyo, but Cassandra worked fine. But later, the same data was found to be different between two regions. That's when I realized "CAP isn't theory—it's a practical choice."

CAP Theorem only applies to "network partition situations." What about when network is normal? There's still a trade-off. That's PACELC Theorem.

For example, MongoDB is a "PC/EC" system. It prioritizes consistency (C) both during partition and normal operation, so Latency might be slightly slower. Conversely, Cassandra is a "PA/EL" system. It prioritizes availability (A) and Latency (L), so it's fast but consistency is weaker.

What if data exceeds tens of terabytes? One server can't hold it. You need to split it. This is Sharding.

The best analogy for sharding is a "moving company."

The problem is, if you split trucks, you need to decide "which truck gets which stuff." This is the sharding strategy.

Determine shard by hashing user ID.

# Shard determination formula

shard_id = hash(user_id) % 4 # 4 servers

# Example

hash("user_12345") % 4 = 2 → Store in Shard 2

hash("user_99999") % 4 = 1 → Store in Shard 1

Advantage: Data is evenly distributed.

Disadvantage: What if you add servers? For example, 4 → 5 servers, formula changes from % 4 to % 5. Then 80% of existing data must move to different shards. This is the Resharding problem.

Solution: Consistent Hashing. Arrange servers in a "Ring" structure, so adding servers only moves some data.

# Consistent Hashing example

ring = [Shard_1: 0°, Shard_2: 90°, Shard_3: 180°, Shard_4: 270°]

hash("user_12345") = 120° → Store in Shard_3 (first shard after 120°)

# Add Shard_5 at 45°?

→ Only move data in 0° ~ 45° range to Shard_5 (only 12.5% of total!)

Split shards by ID range.

Shard 1: user_id 1 ~ 1,000,000

Shard 2: user_id 1,000,001 ~ 2,000,000

Shard 3: user_id 2,000,001 ~ 3,000,000

Advantage: Fast range queries. Queries like WHERE user_id BETWEEN 1 AND 10000 only need Shard 1.

Disadvantage: Hotspot problem. For example, if only recent users (3,000,000 range) are active, only Shard 3 gets overloaded.

I experienced this when doing Range Sharding based on post ID. Only recent posts (high IDs) had many queries, so the last shard hit 100% CPU. Eventually switched to Hash Sharding to fix it.

Theory alone isn't enough. Let's feel the difference with actual code.

-- Users table

CREATE TABLE users (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(50)

);

-- Orders table

CREATE TABLE orders (

id INT PRIMARY KEY,

user_id INT,

product VARCHAR(50),

FOREIGN KEY (user_id) REFERENCES users(id)

);

-- Query user and orders (JOIN required)

SELECT u.name, o.product

FROM users u

JOIN orders o ON u.id = o.user_id

WHERE u.id = 123;

Advantage: No data duplication (normalization). Changing user name only requires updating one place.

Disadvantage: JOINs are slow. Need to scan and match two tables. (Worst case O(N*M))

// MongoDB: Everything in one Document

{

"_id": 123,

"name": "Kim",

"orders": [

{ "product": "iPhone", "price": 1000000 },

{ "product": "MacBook", "price": 2000000 }

]

}

// Query user and orders (No JOIN, one query!)

db.users.findOne({ "_id": 123 });

Advantage: No JOIN, so it's fast. Reads are simple.

Disadvantage: Data duplication. If same product is in multiple users' orders, product info duplicates. Changing product price requires updating all Documents.

When to use SQL vs MongoDB?

To maximize database performance, you need to use cache. The most popular is Redis.

# Check cache → Query DB → Store cache

import redis

r = redis.Redis()

def get_user(user_id):

# 1. Check cache first

cached = r.get(f"user:{user_id}")

if cached:

return cached # Cache hit!

# 2. Cache miss → Query DB

user = db.query(f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = {user_id}")

# 3. Store in cache (TTL 1 hour)

r.setex(f"user:{user_id}", 3600, user)

return user

Advantage: Works even when cache is empty. Only stores in cache when needed.

Disadvantage: Cache miss increases Latency. (Two queries: Cache + DB)

# Update cache and DB simultaneously when writing

def update_user(user_id, name):

# 1. Update DB

db.execute(f"UPDATE users SET name = '{name}' WHERE id = {user_id}")

# 2. Update cache too

r.set(f"user:{user_id}", name)

Advantage: Cache and DB are always synchronized.

Disadvantage: Write performance is slower. (Two writes)

I first properly used caching when reducing API response time. DB query took 500ms, but adding Redis cache reduced it to 5ms. 100x improvement. That moment, I accepted "cache is not optional—it's essential."