큐(Queue): 공평함의 미학 (완전정복)

맛집 줄 서기부터 롤(LoL) 매칭, 그리고 백엔드의 핵심인 메시지 큐(Kafka)까지. 선형 큐의 문제점, 원형 큐(Ring Buffer) 구현, 그리고 스레드 안전한 Blocking Queue까지 파헤칩니다.

맛집 줄 서기부터 롤(LoL) 매칭, 그리고 백엔드의 핵심인 메시지 큐(Kafka)까지. 선형 큐의 문제점, 원형 큐(Ring Buffer) 구현, 그리고 스레드 안전한 Blocking Queue까지 파헤칩니다.

내 서버는 왜 걸핏하면 뻗을까? OS가 한정된 메모리를 쪼개 쓰는 처절한 사투. 단편화(Fragmentation)와의 전쟁.

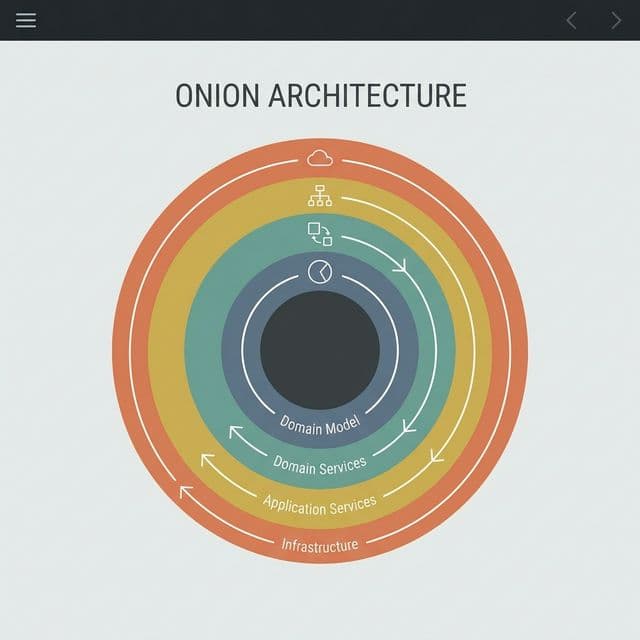

로버트 C. 마틴(Uncle Bob)이 제안한 클린 아키텍처의 핵심은 무엇일까요? 양파 껍질 같은 계층 구조와 의존성 규칙(Dependency Rule)을 통해 프레임워크와 UI로부터 독립적인 소프트웨어를 만드는 방법을 정리합니다.

미로를 탈출하는 두 가지 방법. 넓게 퍼져나갈 것인가(BFS), 한 우물만 팔 것인가(DFS). 최단 경로는 누가 찾을까?

이름부터 빠릅니다. 피벗(Pivot)을 기준으로 나누고 또 나누는 분할 정복 알고리즘. 왜 최악엔 느린데도 가장 많이 쓰일까요?

유명한 식당 앞에 줄을 섭니다. 30분 정도 기다렸을까요. 드디어 5번째쯤 됐을 때, 누군가 새치기를 합니다. 순간 모든 사람의 시선이 그 사람에게 쏠립니다. 왜냐고요? 먼저 온 사람이 먼저 들어가야 한다는 암묵적 규칙을 깼기 때문입니다.

이 규칙은 너무나 당연해 보이지만, 나는 이 규칙이 단순한 도덕의 문제가 아니라 효율성의 문제라는 걸 나중에 이해했습니다. 만약 새치기가 허용된다면? 사람들은 전략적으로 타이밍을 노릴 겁니다. 줄은 무질서해지고, 결국 아무도 예측할 수 없는 상황이 됩니다. 실제로 들어가는 시간은 오히려 더 늦어질 겁니다.

컴퓨터 과학에서는 이 간단하고 공평한 규칙을 큐(Queue)라고 부릅니다. 선입선출(FIFO: First In First Out). 먼저 온 놈이 먼저 나간다. 나는 스택을 공부할 때 "후입선출이 언제 쓰이지?"라고 의아했는데, 큐는 달랐습니다. 일상에서 큐는 공평함을 구현하는 가장 기본적인 도구였고, 이게 컴퓨터 시스템 전반에 녹아들어 있다는 사실이 와닿았습니다.

큐가 제공하는 연산은 정말 단순합니다.

처음 봤을 땐 "이게 뭐가 중요해?"라고 생각했습니다. 그냥 리스트 쓰면 되는 거 아닌가? 근데 실제로 구현해보니 문제가 하나씩 보이기 시작했습니다.

처음에 나는 배열로 큐를 만들면 된다고 생각했습니다. Python의 list로 이렇게 구현했습니다.

queue = ["A", "B", "C"]

# Dequeue: 맨 앞 제거

queue.pop(0) # "A"가 나감

queue.pop(0) # "B"가 나감

문제는 pop(0)이 O(N)이라는 사실이었습니다. 맨 앞 원소를 제거하면, 나머지 원소들(["C"])이 전부 한 칸씩 앞으로 당겨집니다. 원소가 1000개면? 999개를 복사해야 합니다. 만약 초당 10만 건의 요청을 처리하는 서버에서 이런 큐를 쓴다면? 서버가 멈춥니다.

그래서 나는 다른 접근을 시도했습니다. "그럼 포인터를 쓰면 되지 않을까?" front 인덱스를 두고, dequeue할 때마다 front += 1만 하는 겁니다.

queue = ["A", "B", "C", "D"]

front = 0

rear = 3

# Dequeue

front += 1 # 이제 front는 1, "B"를 가리킴

front += 1 # 이제 front는 2, "C"를 가리킴

이제 O(1)입니다. 완벽해 보였습니다. 근데 다시 문제가 생겼습니다. 계속 뒤로만 데이터를 추가하다 보면 배열의 끝에 도달합니다. 앞쪽에는 이미 사용한 공간이 비어있는데, 그 공간을 재활용할 방법이 없습니다.

[X, X, C, D, E, F, G, ...끝]

앞쪽의 X는 이미 dequeue된 빈 공간입니다. 하지만 rear는 계속 오른쪽으로만 전진합니다. 배열 크기를 늘려야 할까요? 그럼 메모리 낭비가 심합니다. 남은 데이터를 앞으로 다 복사할까요? 그럼 다시 O(N)입니다.

나는 이 딜레마에 빠져서 한참을 고민했습니다. 그리고 드디어 답을 찾았습니다.

배열의 끝과 시작을 이어붙이면 됩니다. 논리적으로 배열을 원처럼 만드는 겁니다. 이게 바로 원형 큐(Circular Queue) 또는 링 버퍼(Ring Buffer)입니다.

핵심은 모듈러 연산(%)입니다.

MAX_SIZE = 8

rear = 7 # 배열의 마지막 인덱스

# 다음 위치를 계산

rear = (rear + 1) % MAX_SIZE # (7 + 1) % 8 = 0

rear가 배열의 끝(7)에 도달하면, (7 + 1) % 8 = 0이 되어 다시 처음(0)으로 돌아갑니다. 마치 둥근 트랙을 계속 도는 것처럼 배열을 무한히 재활용할 수 있습니다.

이 방식을 처음 이해했을 때, 나는 "이게 진짜 컴퓨터과학의 핵심이구나"라고 느꼈습니다. 복잡한 알고리즘이 아니라, 단순한 수학(모듈러)으로 근본적인 문제를 해결했습니다. O(1) 삽입, O(1) 삭제, 메모리 재활용까지. 완벽합니다.

class CircularQueue:

def __init__(self, size):

self.size = size

self.queue = [None] * size

self.front = 0

self.rear = 0

self.count = 0 # 현재 원소 개수

def enqueue(self, item):

if self.count == self.size:

raise Exception("Queue is full")

self.queue[self.rear] = item

self.rear = (self.rear + 1) % self.size

self.count += 1

def dequeue(self):

if self.count == 0:

raise Exception("Queue is empty")

item = self.queue[self.front]

self.queue[self.front] = None # 메모리 정리

self.front = (self.front + 1) % self.size

self.count -= 1

return item

def is_empty(self):

return self.count == 0

def is_full(self):

return self.count == self.size

실제로 네트워크 드라이버, 키보드 입력 버퍼, 프린터 대기열 같은 곳에서 이 원형 큐가 사용됩니다. 하드웨어 레벨에서도 이 패턴이 통한다는 게 놀라웠습니다.

큐를 처음 제대로 활용한 건 BFS(Breadth-First Search)를 구현할 때였습니다. 미로 찾기 문제를 풀고 있었는데, DFS는 구현했는데 BFS는 막막했습니다.

BFS의 핵심은 현재 위치의 모든 이웃을 먼저 방문하고, 그다음 이웃의 이웃을 방문하는 것입니다. 이게 큐 없이는 불가능합니다. 왜냐하면 "먼저 발견한 이웃을 먼저 방문"해야 하기 때문입니다. FIFO죠.

from collections import deque

def bfs(graph, start):

visited = set()

queue = deque([start])

visited.add(start)

while queue:

node = queue.popleft() # Dequeue

print(node, end=" ")

# 인접 노드를 큐에 추가 (Enqueue)

for neighbor in graph[node]:

if neighbor not in visited:

visited.add(neighbor)

queue.append(neighbor)

# 예제 그래프

graph = {

'A': ['B', 'C'],

'B': ['A', 'D', 'E'],

'C': ['A', 'F'],

'D': ['B'],

'E': ['B', 'F'],

'F': ['C', 'E']

}

bfs(graph, 'A') # 출력: A B C D E F

이 코드를 돌려보니, 최단 경로를 찾는 건 큐의 FIFO 특성 덕분이라는 게 명확히 이해됐습니다. 만약 스택을 쓰면 DFS가 되어 깊이 우선으로 탐색하게 됩니다. 큐와 스택의 차이가 탐색 순서 전체를 바꾼다는 사실이 신기했습니다.

나는 비전공자라서 JavaScript를 먼저 배웠는데, "JavaScript는 싱글 스레드인데 어떻게 비동기를 처리하지?"라는 의문이 있었습니다. 답은 태스크 큐(Task Queue)였습니다.

console.log("1");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("2");

}, 0);

console.log("3");

// 출력: 1 3 2

왜 setTimeout(..., 0)인데도 "2"가 마지막에 출력될까요? 이벤트 루프가 다음 순서로 작동하기 때문입니다.

console.log("1"), console.log("3")setTimeout의 콜백은 태스크 큐(Queue)에 들어갑니다. 그리고 FIFO 순서로 실행됩니다. 만약 여러 개의 setTimeout이 동시에 완료되면, 먼저 등록된 것이 먼저 실행됩니다.

setTimeout(() => console.log("A"), 0);

setTimeout(() => console.log("B"), 0);

setTimeout(() => console.log("C"), 0);

// 출력: A B C (FIFO)

나는 이걸 이해하고 나서야 "JavaScript의 비동기는 큐로 구현된다"는 사실을 받아들였습니다. Promise, async/await도 결국 마이크로태스크 큐(Microtask Queue)라는 별도의 큐를 사용합니다. 큐가 없으면 JavaScript의 비동기 시스템 자체가 무너집니다.

백엔드를 공부하면서 가장 큰 깨달음은 "큐가 시스템을 살린다"는 것이었습니다. 내가 만든 첫 번째 서비스는 트래픽이 적어서 문제가 없었는데, 사용자가 늘어나면서 서버가 자주 죽었습니다.

문제는 이거였습니다. 주문이 동시에 1000개 들어오면, DB가 1000개의 쓰기 요청을 동시에 처리하려다 터집니다. MySQL은 동시 커넥션 수가 제한되어 있고, 디스크 I/O도 한계가 있습니다.

해결책은 메시지 큐였습니다. 주문을 받으면 일단 Kafka 큐에 넣고 즉시 응답을 반환합니다. 그리고 별도의 워커 프로세스가 큐에서 하나씩 꺼내서 처리합니다.

[사용자] → [웹서버] → [Kafka Queue] → [워커] → [DB]

이렇게 하면:

이 패턴을 비동기 처리(Asynchronous Processing)라고 부릅니다. 큐가 없으면 구현 불가능합니다. 나는 이 구조를 적용하고 나서야 "이래서 Kafka가 필수구나"라고 이해했습니다.

from collections import deque

import time

# 주문 큐

order_queue = deque()

# Producer: 주문 생성

def create_order(order_id):

order_queue.append(order_id)

print(f"주문 생성: {order_id}")

# Consumer: 주문 처리

def process_orders():

while order_queue:

order_id = order_queue.popleft()

print(f"처리 중: {order_id}")

time.sleep(0.5) # DB 저장 시뮬레이션

print(f"완료: {order_id}")

# 시뮬레이션

for i in range(5):

create_order(f"Order-{i+1}")

process_orders()

실제로는 Redis의 LPUSH/RPOP, AWS SQS, RabbitMQ 같은 전문 도구를 씁니다. 하지만 원리는 동일합니다. 큐로 생산(Producer)과 소비(Consumer)를 분리하는 겁니다.

멀티스레드 환경에서 큐를 사용할 때, 나는 처음에 이런 코드를 짰습니다.

from threading import Thread

from collections import deque

queue = deque()

def consumer():

while True:

if queue:

item = queue.popleft()

print(f"처리: {item}")

# 문제: 큐가 비면 무한 루프로 CPU 낭비

문제는 큐가 비었을 때입니다. 위 코드는 while True로 무한히 돌면서 CPU를 낭비합니다. 그렇다고 time.sleep()을 넣으면 응답 속도가 느려집니다.

해결책은 Blocking Queue입니다. Python의 queue.Queue는 내부적으로 락(Lock)과 조건 변수(Condition Variable)를 사용해서, 큐가 비면 스레드를 자동으로 대기 상태로 만듭니다. 데이터가 들어오면 OS가 스레드를 깨웁니다.

from queue import Queue

from threading import Thread

import time

q = Queue()

def producer():

for i in range(5):

time.sleep(1)

q.put(f"Item-{i+1}")

print(f"생산: Item-{i+1}")

def consumer():

while True:

item = q.get() # 큐가 비면 여기서 Block됨 (CPU 낭비 없음)

print(f"소비: {item}")

q.task_done()

Thread(target=producer, daemon=True).start()

Thread(target=consumer, daemon=True).start()

time.sleep(6) # 메인 스레드 대기

q.get()이 Blocking됩니다. 큐가 비면 스레드는 잠들고, q.put()이 호출되면 자동으로 깨어납니다. 이게 생산자-소비자 패턴(Producer-Consumer Pattern)의 정석입니다.

나는 이 패턴을 이해하고 나서야 "스레드 프로그래밍에서 큐가 이렇게 중요하구나"라고 정리해본다.

큐는 한쪽으로 넣고 반대쪽으로 뺍니다. 근데 양쪽 모두에서 넣고 빼야 하는 경우도 있습니다. 이게 덱(Deque, Double-Ended Queue)입니다.

Python에서 collections.deque는 덱입니다. 큐로도 쓸 수 있고, 스택으로도 쓸 수 있습니다.

from collections import deque

d = deque([2, 3])

# 앞쪽에 추가/제거

d.appendleft(1) # [1, 2, 3]

d.popleft() # [2, 3]

# 뒤쪽에 추가/제거

d.append(4) # [2, 3, 4]

d.pop() # [2, 3]

알고리즘 문제 중에 "크기 k인 윈도우를 오른쪽으로 밀면서 각 윈도우의 최댓값을 구하라"는 문제가 있습니다. 덱을 쓰면 O(N)에 풀립니다.

from collections import deque

def max_sliding_window(nums, k):

dq = deque() # 인덱스를 저장

result = []

for i, num in enumerate(nums):

# 윈도우를 벗어난 원소 제거

if dq and dq[0] < i - k + 1:

dq.popleft()

# 현재 원소보다 작은 원소들 제거 (어차피 최댓값이 될 수 없음)

while dq and nums[dq[-1]] < num:

dq.pop()

dq.append(i)

# 윈도우가 완성되면 최댓값 기록

if i >= k - 1:

result.append(nums[dq[0]])

return result

# 예제

nums = [1, 3, -1, -3, 5, 3, 6, 7]

k = 3

print(max_sliding_window(nums, k)) # [3, 3, 5, 5, 6, 7]

덱의 앞뒤 모두 접근 가능하다는 특성 덕분에 O(N)이 가능합니다. 일반 큐로는 불가능합니다.

큐는 무조건 먼저 온 순서대로 처리합니다. 하지만 현실에서는 우선순위가 필요한 경우가 많습니다. 응급실에서는 심각한 환자부터 치료하고, CPU 스케줄러는 중요한 프로세스부터 실행합니다.

이럴 때 우선순위 큐(Priority Queue)를 씁니다. 내부적으로 힙(Heap) 자료구조를 사용해서, 우선순위가 높은 원소를 O(log N)에 꺼냅니다.

import heapq

# Python의 heapq는 최소 힙

pq = []

# (우선순위, 데이터) 형태로 삽입

heapq.heappush(pq, (3, "Low priority"))

heapq.heappush(pq, (1, "High priority"))

heapq.heappush(pq, (2, "Medium priority"))

# 우선순위 순으로 pop

while pq:

priority, task = heapq.heappop(pq)

print(f"처리: {task} (우선순위: {priority})")

# 출력:

# 처리 - High priority (우선순위: 1)

# 처리 - Medium priority (우선순위: 2)

# 처리 - Low priority (우선순위: 3)

우선순위 큐는 Dijkstra 알고리즘, A* 알고리즘, 작업 스케줄링에서 필수입니다. 일반 큐와는 완전히 다른 용도입니다.

처음에는 "다 비슷한 거 아니야?"라고 생각했는데, 각각의 쓰임새가 명확히 달랐습니다.

| 자료구조 | 특징 | 사용 사례 |

|---|---|---|

| Stack | LIFO (후입선출) | 함수 호출 스택, 괄호 검사, DFS |

| Queue | FIFO (선입선출) | BFS, 프린터 대기열, 메시지 큐 |

| Deque | 양쪽 끝 접근 | 슬라이딩 윈도우, 양방향 탐색 |

| Priority Queue | 우선순위 순 | Dijkstra, CPU 스케줄링, 병합 정렬 |

선택 기준:

나는 이 표를 정리하고 나서야 "이제 문제를 보면 어떤 자료구조를 써야 할지 보인다"는 느낌을 받았습니다.

큐를 처음 배울 땐 "그냥 줄 서기잖아"라고 생각했습니다. 하지만 깊이 파고들수록 큐는 시스템을 안정적으로 만드는 핵심 도구라는 걸 이해했습니다.

결국 큐는 공평함이라는 단순한 원칙을 효율적으로 구현한 자료구조였습니다. 나는 이제 큐를 볼 때마다 "이게 왜 필요한지"가 명확히 보입니다. 그리고 그게 내가 큐를 진짜 이해했다는 증거라고 받아들였습니다.

You're standing in line at a famous restaurant. You've been waiting for about 30 minutes. Finally, you're fifth in line. Then someone cuts in front. Instantly, every eye turns to that person. Why? Because they broke the unspoken rule: first come, first served.

This rule seems obvious, but I later realized it's not just about morality—it's about efficiency. If cutting were allowed, people would strategically game the system. The line would become chaotic, unpredictable. Ironically, everyone would wait longer.

In computer science, this simple and fair rule is called a Queue. FIFO (First In First Out). First one in, first one out. When I studied stacks, I wondered, "When would LIFO ever be useful?" But queues were different. I saw them everywhere in daily life—queues implement fairness, and this principle is deeply embedded in computer systems.

That realization hit me hard.

A queue provides remarkably simple operations:

At first, I thought, "What's the big deal? Just use a list." But when I tried implementing it, problems emerged one by one.

Initially, I thought implementing a queue with an array was straightforward. I tried it in Python with a list:

queue = ["A", "B", "C"]

# Dequeue: Remove from front

queue.pop(0) # "A" leaves

queue.pop(0) # "B" leaves

The problem? pop(0) is O(N). When you remove the first element, all remaining elements (["C"]) must shift left by one position. If you have 1,000 elements? You copy 999 of them. Imagine using this in a server handling 100,000 requests per second. Your server would grind to a halt.

So I tried a different approach: "What if I use pointers instead?" I'd keep a front index, and on each dequeue, just do front += 1.

queue = ["A", "B", "C", "D"]

front = 0

rear = 3

# Dequeue

front += 1 # Now front is 1, pointing to "B"

front += 1 # Now front is 2, pointing to "C"

Now it's O(1). Perfect, right? But then another problem arose. As I kept adding data to the rear, I'd eventually hit the end of the array. The front section had unused space, but I couldn't reclaim it.

[X, X, C, D, E, F, G, ...end]

The X marks are wasted space from dequeued elements. But rear keeps moving right. Should I resize the array? That wastes memory. Should I copy all remaining data forward? That's O(N) again.

I was stuck in this dilemma for a while. Then I found the answer.

Connect the end of the array to the beginning. Logically, turn the array into a circle. This is the Circular Queue or Ring Buffer.

The key is the modulo operation (%).

MAX_SIZE = 8

rear = 7 # Last index

# Calculate next position

rear = (rear + 1) % MAX_SIZE # (7 + 1) % 8 = 0

When rear reaches the array's end (7), (7 + 1) % 8 = 0 wraps it back to the beginning (0). Like running laps on a circular track, you can reuse the array indefinitely.

When I first understood this, I thought, "This is the essence of computer science." Not a complex algorithm—a simple math operation (modulo) solving a fundamental problem. O(1) insert, O(1) delete, memory reuse. Perfect.

class CircularQueue {

constructor(size) {

this.size = size;

this.queue = new Array(size);

this.front = 0;

this.rear = 0;

this.count = 0;

}

enqueue(item) {

if (this.count === this.size) {

throw new Error("Queue is full");

}

this.queue[this.rear] = item;

this.rear = (this.rear + 1) % this.size;

this.count++;

}

dequeue() {

if (this.count === 0) {

throw new Error("Queue is empty");

}

const item = this.queue[this.front];

this.queue[this.front] = null;

this.front = (this.front + 1) % this.size;

this.count--;

return item;

}

isEmpty() {

return this.count === 0;

}

isFull() {

return this.count === this.size;

}

}

This pattern is used in network drivers, keyboard input buffers, and printer queues. Even at the hardware level, this pattern holds. That amazed me.

The first time I truly used a queue was implementing BFS (Breadth-First Search). I was solving a maze problem. I'd implemented DFS, but BFS seemed impossible.

The core of BFS: visit all neighbors of the current node first, then visit neighbors of those neighbors. Without a queue, this is impossible. Why? Because you must "visit the first-discovered neighbor first." FIFO.

function bfs(graph, start) {

const visited = new Set();

const queue = [start];

visited.add(start);

const result = [];

while (queue.length > 0) {

const node = queue.shift(); // Dequeue

result.push(node);

// Enqueue adjacent nodes

for (const neighbor of graph[node]) {

if (!visited.has(neighbor)) {

visited.add(neighbor);

queue.push(neighbor);

}

}

}

return result;

}

// Example graph

const graph = {

'A': ['B', 'C'],

'B': ['A', 'D', 'E'],

'C': ['A', 'F'],

'D': ['B'],

'E': ['B', 'F'],

'F': ['C', 'E']

};

console.log(bfs(graph, 'A')); // Output: A B C D E F

Running this code, I clearly understood: finding the shortest path works because of the queue's FIFO nature. If you use a stack instead, you get DFS, which explores depth-first. The difference between a queue and a stack completely changes the traversal order. That fascinated me.

As a non-CS major, I learned JavaScript first. I had this question: "JavaScript is single-threaded, so how does it handle asynchronous operations?" The answer: the Task Queue.

console.log("1");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("2");

}, 0);

console.log("3");

// Output: 1 3 2

Why does "2" print last, even though setTimeout(..., 0) has zero delay? The Event Loop works like this:

console.log("1"), console.log("3")The setTimeout callback enters the Task Queue. It executes in FIFO order. If multiple setTimeout calls complete simultaneously, the first registered executes first.

setTimeout(() => console.log("A"), 0);

setTimeout(() => console.log("B"), 0);

setTimeout(() => console.log("C"), 0);

// Output: A B C (FIFO)

After understanding this, I accepted the fact: "JavaScript's async system is built on queues." Promises and async/await also use a separate Microtask Queue. Without queues, JavaScript's async system would collapse.

My biggest backend insight: "Queues save systems." My first service had low traffic, so no issues. But as users grew, the server crashed frequently.

The problem: when 1,000 orders arrive simultaneously, the database tries to handle 1,000 write requests at once and crashes. MySQL has a connection limit, and disk I/O has limits too.

The solution: Message Queues. When an order arrives, immediately put it in a Kafka queue and return a response. A separate worker process pulls from the queue one by one and processes them.

[User] → [Web Server] → [Kafka Queue] → [Worker] → [DB]

Benefits:

This pattern is called Asynchronous Processing. Without queues, it's impossible. After implementing this architecture, I understood: "This is why Kafka is essential."

class PrintQueue {

constructor() {

this.queue = [];

this.processing = false;

}

addJob(document) {

this.queue.push(document);

console.log(`Added to queue: ${document}`);

this.processQueue();

}

async processQueue() {

if (this.processing || this.queue.length === 0) return;

this.processing = true;

while (this.queue.length > 0) {

const doc = this.queue.shift(); // Dequeue

console.log(`Printing: ${doc}`);

await this.simulatePrinting();

console.log(`Completed: ${doc}`);

}

this.processing = false;

}

simulatePrinting() {

return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 1000));

}

}

// Usage

const printer = new PrintQueue();

printer.addJob("Document1.pdf");

printer.addJob("Document2.pdf");

printer.addJob("Document3.pdf");

In reality, you'd use Redis (LPUSH/RPOP), AWS SQS, or RabbitMQ. But the principle is the same: use a queue to decouple production from consumption.

In multi-threaded environments, using a queue initially led me to write code like this:

// Naive approach (BAD)

const queue = [];

function consumer() {

while (true) {

if (queue.length > 0) {

const item = queue.shift();

console.log(`Processing: ${item}`);

}

// Problem: Wastes CPU when queue is empty

}

}

The problem occurs when the queue is empty. The code loops infinitely, wasting CPU. Adding a sleep() slows response time.

The solution: Blocking Queue. In languages with proper concurrency primitives (like Java's BlockingQueue or Python's queue.Queue), the queue uses locks and condition variables to automatically put threads to sleep when empty. When data arrives, the OS wakes the thread.

class TokenBucket {

constructor(capacity, refillRate) {

this.capacity = capacity;

this.tokens = capacity;

this.refillRate = refillRate; // tokens per second

setInterval(() => {

this.tokens = Math.min(this.capacity, this.tokens + this.refillRate);

}, 1000);

}

async consume() {

while (this.tokens < 1) {

await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 100)); // Wait

}

this.tokens--;

return true;

}

}

// API rate limiting example

const bucket = new TokenBucket(10, 2); // 10 tokens, refill 2/sec

async function makeAPICall(id) {

await bucket.consume();

console.log(`API call ${id} executed`);

}

// Burst of 15 calls - only 10 go through immediately

for (let i = 1; i <= 15; i++) {

makeAPICall(i);

}

After understanding this pattern, I concluded: "Queues are critical in thread programming."

A queue inserts at one end and removes from the other. But sometimes you need to insert and remove from both ends. That's a Deque (Double-Ended Queue).

// JavaScript doesn't have native Deque, but we can simulate

class Deque {

constructor() {

this.items = [];

}

addFront(item) { this.items.unshift(item); }

addRear(item) { this.items.push(item); }

removeFront() { return this.items.shift(); }

removeRear() { return this.items.pop(); }

isEmpty() { return this.items.length === 0; }

}

const deque = new Deque();

deque.addRear(2); // [2]

deque.addRear(3); // [2, 3]

deque.addFront(1); // [1, 2, 3]

deque.removeRear(); // [1, 2]

Algorithm problem: "Given an array and window size k, find the maximum in each window as it slides right." With a deque, this is O(N).

function maxSlidingWindow(nums, k) {

const deque = []; // Store indices

const result = [];

for (let i = 0; i < nums.length; i++) {

// Remove indices outside window

if (deque.length && deque[0] < i - k + 1) {

deque.shift();

}

// Remove indices of smaller elements (they can't be max)

while (deque.length && nums[deque[deque.length - 1]] < nums[i]) {

deque.pop();

}

deque.push(i);

// Once window is full, record max

if (i >= k - 1) {

result.push(nums[deque[0]]);

}

}

return result;

}

// Example

const nums = [1, 3, -1, -3, 5, 3, 6, 7];

const k = 3;

console.log(maxSlidingWindow(nums, k)); // [3, 3, 5, 5, 6, 7]

The deque's access to both ends makes O(N) possible. A regular queue can't do this.

Initially, I thought, "Aren't they all similar?" But each has distinct use cases.

| Data Structure | Characteristic | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Stack | LIFO (Last In First Out) | Function call stack, bracket validation, DFS |

| Queue | FIFO (First In First Out) | BFS, print queue, message queue |

| Deque | Access both ends | Sliding window, bidirectional search |

| Priority Queue | Priority order | Dijkstra, CPU scheduling, merge sort |

Selection criteria:

After organizing this table, I felt: "Now I can see which data structure to use when I see a problem."

In production systems, you rarely implement queues from scratch. Instead, you use battle-tested services:

const AWS = require('aws-sdk');

const sqs = new AWS.SQS();

const queueURL = 'https://sqs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/123456789/my-queue';

// Enqueue

async function sendMessage(message) {

const params = {

QueueUrl: queueURL,

MessageBody: JSON.stringify(message)

};

await sqs.sendMessage(params).promise();

}

// Dequeue

async function receiveMessages() {

const params = {

QueueUrl: queueURL,

MaxNumberOfMessages: 10,

WaitTimeSeconds: 20 // Long polling

};

const data = await sqs.receiveMessage(params).promise();

return data.Messages || [];

}

const redis = require('redis');

const client = redis.createClient();

// Enqueue (RPUSH = push to right/rear)

await client.rPush('jobs', JSON.stringify({ task: 'send-email', userId: 123 }));

// Dequeue (LPOP = pop from left/front)

const job = await client.lPop('jobs');

console.log(JSON.parse(job));

These services handle durability, replication, and monitoring. You focus on business logic.