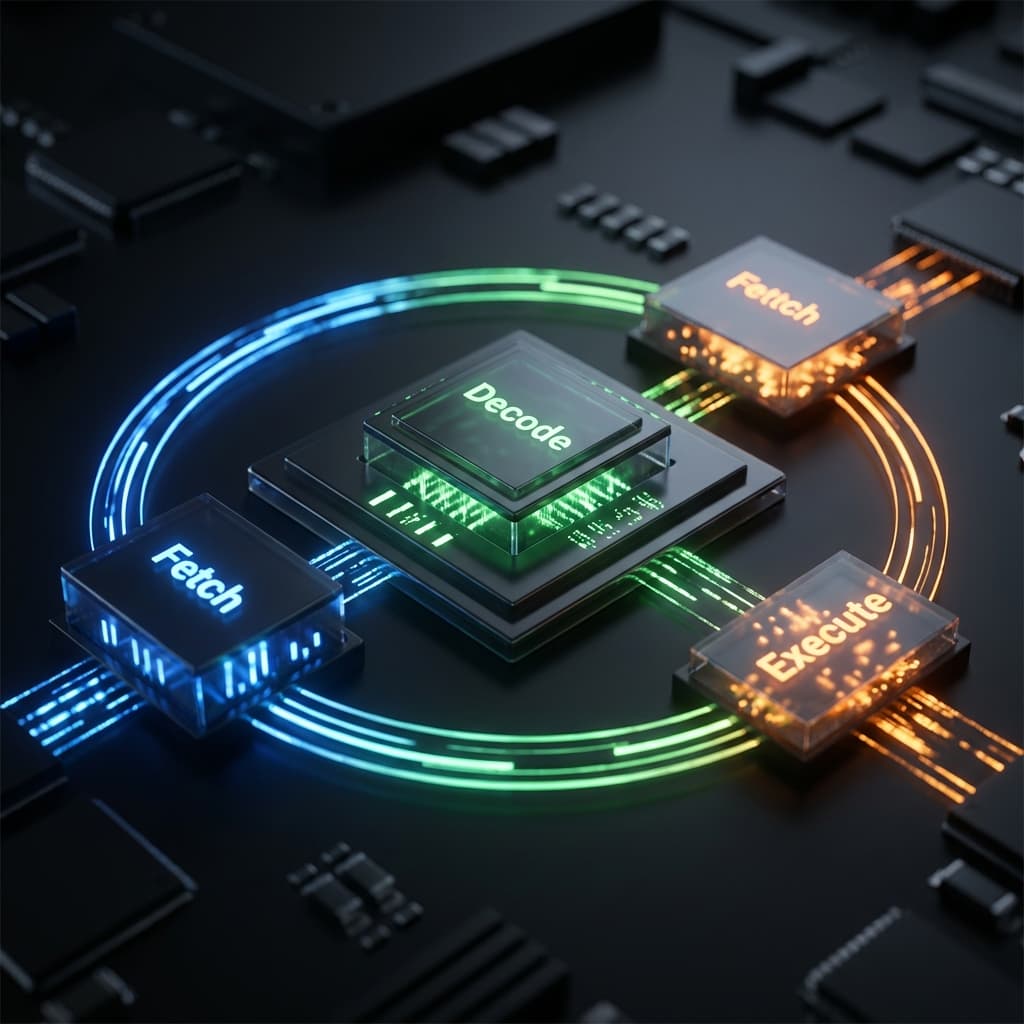

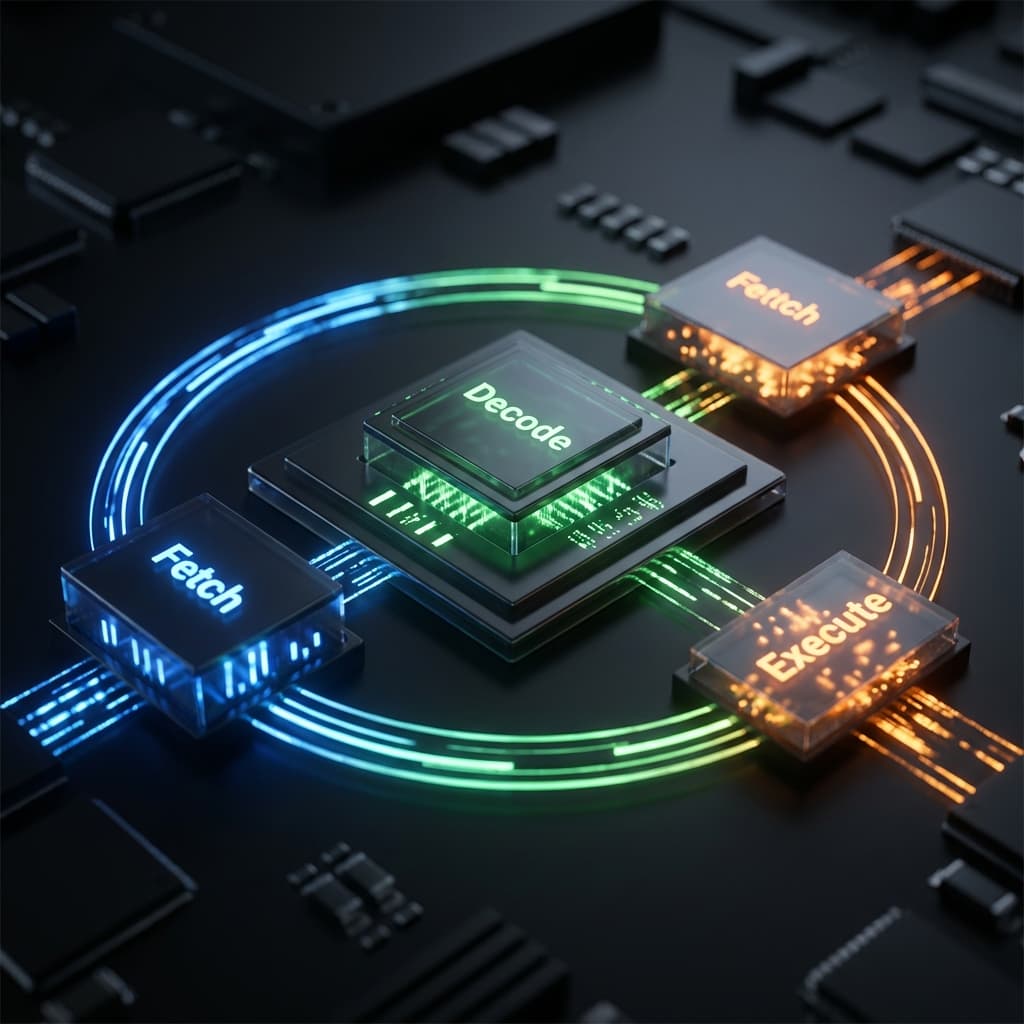

명령어 사이클: Fetch-Decode-Execute

CPU가 숨 쉬는 법. 1초에 수십억 번 반복되는 이 3단계 리듬이 컴퓨터의 생명입니다.

CPU가 숨 쉬는 법. 1초에 수십억 번 반복되는 이 3단계 리듬이 컴퓨터의 생명입니다.

내 서버는 왜 걸핏하면 뻗을까? OS가 한정된 메모리를 쪼개 쓰는 처절한 사투. 단편화(Fragmentation)와의 전쟁.

미로를 탈출하는 두 가지 방법. 넓게 퍼져나갈 것인가(BFS), 한 우물만 팔 것인가(DFS). 최단 경로는 누가 찾을까?

이름부터 빠릅니다. 피벗(Pivot)을 기준으로 나누고 또 나누는 분할 정복 알고리즘. 왜 최악엔 느린데도 가장 많이 쓰일까요?

매번 3-Way Handshake 하느라 지쳤나요? 한 번 맺은 인연(TCP 연결)을 소중히 유지하는 법. HTTP 최적화의 기본.

회사를 창업하고 나서 가장 먼저 부딪힌 벽이 뭐였냐면, "CPU가 정확히 어떻게 일하는가"였습니다. 전 CS 전공이 아니라서 그동안 그냥 "코드 짜면 컴퓨터가 알아서 돌아간다" 정도로만 이해하고 있었거든요.

그러다가 서버 성능 최적화를 해야 하는 상황이 왔는데, CPU 사용률이 100%를 찍으면서도 "뭐가 문제인지" 전혀 감이 안 오는 거예요. 팀원들은 "명령어 파이프라인이", "분기 예측 실패가" 이런 얘기를 하는데 저는 멍하니 듣기만 했습니다.

그때 깨달았죠. CPU의 기본 리듬을 모르면 최적화는 불가능하다는 걸.

컴퓨터를 살 때 우리는 "3.5GHz"라는 스펙을 봅니다. 근데 이게 정확히 뭘 의미할까요? 1초에 35억 번 뭘 한다는 건데, 그 "뭘"이 대체 뭐란 말입니까?

저는 처음엔 "1초에 35억 개의 명령어를 실행한다"라고 생각했어요. 완전히 틀린 건 아니지만, 정확하지도 않더군요. 실제로는 명령어 하나가 여러 클럭 사이클을 먹기도 하고, 반대로 파이프라이닝 덕분에 여러 명령어가 동시에 진행되기도 하니까요.

그래서 저는 CPU 아키텍처 책을 펼쳤습니다. 그리고 가장 먼저 마주한 개념이 바로 명령어 사이클(Instruction Cycle)이었죠.

결론부터 말하면, CPU는 엄청나게 복잡해 보이지만 사실 평생 똑같은 3단계만 반복하는 단순노동자입니다.

이게 전부입니다. 컴퓨터가 켜진 순간부터 꺼질 때까지, CPU는 이 3단계를 1초에 수십억 번 반복합니다. 마치 심장 박동처럼.

비유하자면 CPU는 레시피를 따라 요리하는 로봇 셰프입니다. 레시피북(메모리)을 펼치고, 한 줄 읽고, 그게 뭔 뜻인지 파악하고, 실행하고, 다음 줄로 넘어가는 걸 무한반복하는 거죠. 단지 이 로봇은 1초에 40억 번 레시피를 읽는다는 게 다를 뿐입니다.

Fetch 단계는 생각보다 복잡합니다. CPU 안에는 여러 특수 레지스터들이 있는데, 이들이 협력해서 명령어를 가져옵니다.

핵심 레지스터 4종 세트:# Fetch 단계의 내부 흐름

1. MAR ← PC // "메모리 100번지 읽어줘"

2. MDR ← Memory[MAR] // 메모리가 데이터 돌려줌 (예: 0x8B450012)

3. IR ← MDR // 명령어 레지스터에 복사

4. PC ← PC + 1 // 다음 명령어 주소로 이동 (책갈피 옮기기)

// 예시: 메모리 100번지에 "ADD R1, R2, R3" 명령어가 있다면

// IR에는 이제 "0x8B450012" (ADD의 이진 표현) 같은 값이 들어있음

여기서 중요한 건 PC는 자동으로 증가한다는 점입니다. 기본적으로 명령어는 순차적으로 실행되니까요. 물론 JUMP나 CALL 같은 분기 명령어가 나오면 PC가 다른 곳으로 튀지만, 기본은 "한 칸씩 앞으로"입니다.

IR에 들어온 명령어는 그냥 0과 1의 나열입니다. 예를 들어 10001011 01000101 00000000 00010010 이런 식이죠. 이걸 제어 장치(Control Unit, CU)가 해석합니다.

명령어는 보통 두 부분으로 나뉩니다:

# 명령어 구조 예시 (가상의 32비트 CPU)

[opcode 6비트][operand1 5비트][operand2 5비트][operand3 5비트][나머지 11비트]

예: ADD R1, R2, R3

→ 100010 | 00001 | 00010 | 00011 | 00000000000

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

ADD R1 R2 R3

Decode 결과:

- 연산: ADD (opcode = 100010)

- 목적지: R1 (결과를 저장할 레지스터)

- 피연산자1: R2

- 피연산자2: R3

CU는 이 해석을 바탕으로 제어 신호를 생성합니다. "ALU야, 덧셈 모드로 전환해", "레지스터 파일아, R2랑 R3 값 내놓아", "결과는 R1에 써" 이런 신호들이죠.

CISC vs RISC의 차이가 바로 여기서 드러납니다:

CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer): 명령어 하나가 여러 동작을 함. 예를 들어 MULT [100], R1, R2 같은 명령어는 "메모리 100번지에서 값을 읽고, R1과 곱하고, R2에 저장"을 한 방에 처리. 디코딩이 복잡하고 실행에 여러 클럭 사이클 소요.

RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer): 명령어를 아주 단순하게. LOAD R1, [100] → MULT R2, R1, R3 → STORE R2, [200] 처럼 여러 단계로 쪼갬. 디코딩은 빠르고 각 명령어는 1~2 클럭에 끝남.

x86은 CISC, ARM은 RISC입니다. 최근 Apple Silicon이 빠른 이유 중 하나가 바로 RISC의 단순함 덕분이죠.

디코딩이 끝나면 실행입니다. 이 단계에서는 주로 ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit)가 일합니다.

# Execute 단계 예시

명령어: ADD R1, R2, R3

디코딩 결과: R1 = R2 + R3

1. 레지스터 파일에서 R2, R3 값을 읽음

R2 = 10, R3 = 25

2. ALU에 입력 전달

ALU_Input_A = 10

ALU_Input_B = 25

ALU_Control = ADD (덧셈 모드)

3. ALU 연산 수행

ALU_Output = 10 + 25 = 35

4. 결과를 R1에 Write-back

R1 ← 35

만약 메모리 접근이 필요한 명령어라면 (예: LOAD R1, [100]), 실행 단계에서 다시 한번 메모리 버스를 타게 됩니다. 이 경우 실행 시간이 더 길어지죠. 메모리 접근은 레지스터 접근보다 수십~수백 배 느리니까요.

이론적으로 Fetch-Decode-Execute가 각각 1클럭 사이클이면 명령어 하나가 3클럭에 끝납니다. 하지만 현실은 복잡합니다:

ADD): 1~2 클럭REP MOVSB): 수십~수백 클럭그래서 3.5GHz CPU가 "1초에 35억 개 명령어 실행"이라고 단순하게 말할 수 없는 겁니다.

CPU 설계자들은 생각했습니다. "Fetch-Decode-Execute를 순차적으로 하니까 너무 느린데, 동시에 못 하나?"

파이프라이닝이 바로 그 답입니다. 마치 공장의 컨베이어 벨트처럼, 여러 명령어를 동시에 처리하는 거죠.

# 파이프라이닝 없을 때 (순차 처리)

Clock 1: [명령어1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [명령어1 Decode]

Clock 3: [명령어1 Execute]

Clock 4: [명령어2 Fetch]

Clock 5: [명령어2 Decode]

Clock 6: [명령어2 Execute]

→ 명령어 2개에 6 클럭 소요

# 파이프라이닝 있을 때 (병렬 처리)

Clock 1: [명령어1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [명령어1 Decode] [명령어2 Fetch]

Clock 3: [명령어1 Execute] [명령어2 Decode] [명령어3 Fetch]

Clock 4: [명령어2 Execute] [명령어3 Decode] [명령어4 Fetch]

Clock 5: [명령어3 Execute] [명령어4 Decode]

→ 명령어 4개에 5 클럭 소요 (이상적인 경우)

이론적으로는 3단계 파이프라인이면 처리량이 3배가 됩니다. 물론 현실은 이상적이지 않지만요.

파이프라이닝은 만능이 아닙니다. 세 가지 위험 요소(Hazards)가 있습니다:

1. 데이터 해저드 (Data Hazard)명령어1: ADD R1, R2, R3 // R1 = R2 + R3

명령어2: SUB R4, R1, R5 // R4 = R1 - R5 (R1이 필요!)

파이프라인:

Clock 1: [명령어1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [명령어1 Decode] [명령어2 Fetch]

Clock 3: [명령어1 Execute] [명령어2 Decode] ← 문제! 명령어2가 R1을 읽으려는데

명령어1이 아직 R1에 결과를 안 썼음!

해결책: 포워딩(Forwarding) 또는 스톨(Stall). 포워딩은 "ALU 출력을 바로 다음 명령어 입력으로" 우회시키는 거고, 스톨은 "잠깐 기다려"입니다.

2. 제어 해저드 (Control Hazard)분기 명령어(JMP, BEQ 등)가 나오면 "다음에 실행할 명령어가 어디 있는지" 모릅니다. 조건이 참이면 A로, 거짓이면 B로 가는데, 조건 평가는 Execute 단계에서야 끝나거든요.

명령어1: BEQ R1, R2, Label // R1 == R2이면 Label로 점프

명령어2: ADD R3, R4, R5 // 순차적인 다음 명령어

명령어3: ...

Clock 1: [명령어1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [명령어1 Decode] [명령어2 Fetch] ← 이게 맞는 명령어인지 모름!

Clock 3: [명령어1 Execute] [명령어2 Decode] ← 여기서야 분기 여부 판단

해결책: 분기 예측(Branch Prediction). CPU가 "아마 분기 안 할 것 같아"라고 예측하고 미리 명령어를 가져옵니다. 틀리면 파이프라인을 비우고(flush) 다시 시작. 현대 CPU는 95% 이상 정확도로 예측합니다.

3. 구조적 해저드 (Structural Hazard)하드웨어 자원(메모리 버스, ALU 등)이 부족해서 동시 실행이 불가능한 경우입니다. 예를 들어 명령어1이 메모리를 읽는 동시에 명령어3이 데이터를 메모리에 쓰려면 충돌이 나죠.

해결책: 하버드 아키텍처 (명령어 메모리와 데이터 메모리 분리) 또는 다중 포트 메모리.

파이프라이닝도 모자라서, 현대 CPU는 더 극단적인 방법을 씁니다:

슈퍼스칼라(Superscalar): 파이프라인을 여러 개 만들어서 한 클럭에 여러 명령어를 동시에 페치. Intel i9은 한 번에 4~6개 명령어를 처리합니다.

비순차 실행(Out-of-Order Execution): 명령어 순서를 지키되, 실행은 "준비된 것부터". 예를 들어 명령어2가 데이터 대기 중이면 명령어3을 먼저 실행하고 나중에 명령어2를 처리.

원래 순서:

1. LOAD R1, [100] // 메모리 읽기 - 느림

2. ADD R2, R1, R3 // R1이 필요 (대기)

3. MUL R4, R5, R6 // R1과 무관 - 독립적

비순차 실행:

1. LOAD R1, [100] 시작

3. MUL R4, R5, R6 실행 (먼저 끝남)

2. ADD R2, R1, R3 실행 (LOAD 끝나면)

→ 전체 실행 시간 단축

이 모든 기법이 "Fetch-Decode-Execute 사이클을 최대한 빠르게 돌리기 위한" 것들입니다.

명령어 사이클이 항상 순조롭게 진행되는 건 아닙니다. 인터럽트(Interrupt)가 발생하면 현재 사이클을 멈추고 다른 일을 해야 합니다.

정상 흐름:

Fetch → Decode → Execute → Fetch → Decode → Execute ...

인터럽트 발생:

Fetch → Decode → Execute → [인터럽트!] →

→ 현재 상태 저장 (PC, 레지스터 등)

→ 인터럽트 핸들러 실행 (Fetch-Decode-Execute)

→ 원래 상태 복구

→ Fetch → Decode → Execute ... (이어서 진행)

인터럽트는 보통 Execute 단계 끝에서 체크됩니다. 키보드 입력, 타이머, 디스크 I/O 완료 같은 게 인터럽트를 발생시키죠. 이게 없으면 CPU는 "외부 세계"를 전혀 모르는 바보가 됩니다.

창업 초기에 저는 실수로 무한 루프 코드를 배포한 적이 있습니다. while (true) 안에 break 조건을 안 넣은 거죠. 서버 CPU가 100%를 찍고, 다른 요청이 전부 먹통이 됐습니다.

그때는 그냥 "아 실수했네"였는데, 명령어 사이클을 공부하고 나니 왜 CPU가 그렇게 혹사당했는지 이해가 됐습니다.

CPU는 "이거 의미 없는데?"라고 판단하지 못합니다. 그냥 주어진 명령어를 Fetch-Decode-Execute로 반복할 뿐이죠. while (true) 안에 i++ 같은 게 있으면, CPU는 1초에 수십억 번 "i 값 읽기 → 1 더하기 → i에 쓰기"를 반복합니다.

파이프라이닝, 분기 예측, 슈퍼스칼라 같은 모든 최적화 기술이 동원돼서 의미 없는 일을 최대한 빠르게 하는 거죠. 마치 헬스장에서 런닝머신을 최고 속도로 돌리는데 앞으로는 안 가는 상황입니다.

현대 CPU의 마법 같은 기술입니다.

if (a > 0) 같은 분기문을 만났을 때, CPU는 결과를 계산하기도 전에 "아마 true일 거야"라고 찍어서 미리 다음 명령어를 실행합니다.이 기술 덕분에 파이프라인이 멈추지 않고 돌아갑니다. 하지만 이게 보안 취약점인 Spectre & Meltdown의 원인이 되기도 했죠. 예측이 틀려서 롤백하더라도, 캐시에 흔적이 남아서 해커가 데이터를 훔쳐볼 수 있었으니까요.

파이프라이닝을 가장 쉽게 이해하는 방법은 "빨래"입니다.

No Pipeline (순차 처리):

Pipeline (병렬 처리):

CPU는 거대한 빨래방입니다. 세탁기(Fetch), 건조기(Decode), 다림질(Execute) 기계가 쉴 새 없이 돌아가야 합니다.

파이프라인이 멈추는 현상을 해저드(Hazard)라고 합니다.

if)에서 어디로 갈지 몰라 미리 빨래를 못 넣을 때.CPU 설계자들은 이 해저드를 없애려고 Forwarding, Branch Prediction, Out-of-Order Execution 같은 눈물겨운 기술들을 개발했답니다.

CPU가 이해하는 명령어(Instruction Set)를 어떻게 설계하느냐에 따라 사이클 효율이 달라집니다.

CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer, 예: Intel x86):

MULT a, b (메모리에서 a, b 읽어서 곱하고 저장해라)RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer, 예: ARM):

LOAD a, LOAD b, PROD a, b, STORE a현대의 x86 CPU는 겉으로는 CISC지만, 내부적으로는 복잡한 명령어를 잘게 쪼개서(Micro-ops) RISC처럼 실행하는 하이브리드 방식을 씁니다.

명령어 사이클을 공부하면서 가장 큰 깨달음은 "CPU는 멍청하고, 그래서 빠르다"는 점입니다.

CPU는 맥락을 이해하지 못합니다. 지금 하는 일이 의미 있는지, 효율적인지 판단하지 못합니다. 그냥 주어진 명령어를 기계적으로, 엄청난 속도로 반복할 뿐이죠.

개발자인 우리의 책임은 명확합니다. CPU에게 좋은 명령서를 주는 것. 불필요한 반복을 줄이고, 캐시 친화적으로 데이터를 배치하고, 분기 예측이 잘되도록 코드를 짜는 것.

여러분이 짠 코드는 지금 이 순간에도 CPU를 춤추게 하고 있습니다. Fetch-Decode-Execute-Fetch-Decode-Execute... 수십억 번의 리듬으로.

그 춤이 우아한 왈츠인지, 아니면 혼란스러운 난투극인지는 여러분의 코드에 달려 있습니다.

When I started my company, the first technical wall I hit wasn't about frameworks or languages. It was about understanding how the CPU actually works. Since I'm not a CS major, I'd always thought of it as "you write code, computer runs it" - a black box.

Then came the day our server pegged at 100% CPU usage, and I had zero intuition about why. My teammates threw around terms like "instruction pipeline stalls" and "branch misprediction penalties," and I just nodded along, completely lost.

That's when I realized: you can't optimize what you don't understand at the fundamental level.

When buying a computer, we see specs like "3.5GHz processor." But what does that number actually represent? It's doing 3.5 billion somethings per second, but what's the something?

I initially thought it meant "3.5 billion instructions per second." Not entirely wrong, but not accurate either. Some instructions take multiple clock cycles, while pipelining allows multiple instructions to progress simultaneously. The truth is more nuanced.

So I cracked open a CPU architecture book, and the first concept I encountered was the instruction cycle - the CPU's fundamental rhythm.

Here's the punchline: despite appearing complex, the CPU is fundamentally a repetitive worker doing the same 3 steps forever:

That's it. From power-on to shutdown, the CPU repeats these three steps billions of times per second. Like a heartbeat.

Think of the CPU as a robot chef following a recipe. It opens the cookbook (memory), reads one line, figures out what it means, executes it, moves to the next line. The only difference? This robot reads 4 billion recipe lines per second.

Fetch is more complex than it sounds. Inside the CPU, several specialized registers collaborate to fetch instructions:

The Four Key Registers:# Internal flow of Fetch stage

1. MAR ← PC // "Read memory address 100"

2. MDR ← Memory[MAR] // Memory returns data (e.g., 0x8B450012)

3. IR ← MDR // Copy to instruction register

4. PC ← PC + 1 // Move to next instruction (advance bookmark)

// Example: If memory address 100 contains "ADD R1, R2, R3"

// IR now holds "0x8B450012" (binary representation of ADD)

The crucial point: PC automatically increments. Instructions normally execute sequentially. Of course, branch instructions like JUMP or CALL can make PC leap elsewhere, but the default is "one step forward."

The instruction in IR is just ones and zeros. Something like 10001011 01000101 00000000 00010010. The Control Unit (CU) interprets this.

Instructions typically have two parts:

# Instruction structure example (hypothetical 32-bit CPU)

[opcode 6 bits][operand1 5 bits][operand2 5 bits][operand3 5 bits][remaining 11 bits]

Example: ADD R1, R2, R3

→ 100010 | 00001 | 00010 | 00011 | 00000000000

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

ADD R1 R2 R3

Decode result:

- Operation: ADD (opcode = 100010)

- Destination: R1 (register to store result)

- Operand1: R2

- Operand2: R3

Based on this interpretation, CU generates control signals: "ALU, switch to addition mode," "Register file, output R2 and R3 values," "Write result to R1."

CISC vs RISC differences emerge here:

CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer): One instruction does multiple operations. Example: MULT [100], R1, R2 reads from memory address 100, multiplies with R1, stores in R2 - all in one instruction. Complex decoding, multiple clock cycles.

RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer): Instructions are ultra-simple. Break it into steps: LOAD R1, [100] → MULT R2, R1, R3 → STORE R2, [200]. Fast decoding, each instruction completes in 1-2 clocks.

x86 is CISC, ARM is RISC. One reason Apple Silicon is fast? RISC simplicity.

After decoding, execution happens. The ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit) does most of the heavy lifting.

# Execute stage example

Instruction: ADD R1, R2, R3

Decode result: R1 = R2 + R3

1. Read R2, R3 values from register file

R2 = 10, R3 = 25

2. Feed inputs to ALU

ALU_Input_A = 10

ALU_Input_B = 25

ALU_Control = ADD (addition mode)

3. ALU performs operation

ALU_Output = 10 + 25 = 35

4. Write-back result to R1

R1 ← 35

If the instruction requires memory access (e.g., LOAD R1, [100]), the execute stage hits the memory bus again. This takes longer since memory access is tens to hundreds of times slower than register access.

Theoretically, if Fetch-Decode-Execute each take 1 clock cycle, one instruction completes in 3 clocks. Reality is messier:

ADD): 1-2 clocksREP MOVSB): tens to hundreds of clocksThat's why a 3.5GHz CPU can't simply claim "3.5 billion instructions per second."

CPU designers thought: "Sequential Fetch-Decode-Execute is too slow. Can we parallelize?"

Pipelining is the answer. Like a factory assembly line, multiple instructions process simultaneously.

# Without pipelining (sequential)

Clock 1: [Instruction1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [Instruction1 Decode]

Clock 3: [Instruction1 Execute]

Clock 4: [Instruction2 Fetch]

Clock 5: [Instruction2 Decode]

Clock 6: [Instruction2 Execute]

→ 2 instructions in 6 clocks

# With pipelining (parallel)

Clock 1: [Instruction1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [Instruction1 Decode] [Instruction2 Fetch]

Clock 3: [Instruction1 Execute] [Instruction2 Decode] [Instruction3 Fetch]

Clock 4: [Instruction2 Execute] [Instruction3 Decode] [Instruction4 Fetch]

Clock 5: [Instruction3 Execute] [Instruction4 Decode]

→ 4 instructions in 5 clocks (ideal case)

Theoretically, a 3-stage pipeline means 3x throughput. Reality isn't ideal, though.

Pipelining isn't magic. Three types of hazards exist:

1. Data HazardInstruction1: ADD R1, R2, R3 // R1 = R2 + R3

Instruction2: SUB R4, R1, R5 // R4 = R1 - R5 (needs R1!)

Pipeline:

Clock 1: [Instruction1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [Instruction1 Decode] [Instruction2 Fetch]

Clock 3: [Instruction1 Execute] [Instruction2 Decode] ← Problem! Instruction2 tries to read R1

but Instruction1 hasn't written result yet!

Solutions: Forwarding or Stall. Forwarding bypasses ALU output directly to next instruction's input. Stall means "wait a moment."

2. Control HazardBranch instructions (JMP, BEQ, etc.) create uncertainty about "which instruction comes next." Condition evaluation finishes in Execute stage.

Instruction1: BEQ R1, R2, Label // Jump to Label if R1 == R2

Instruction2: ADD R3, R4, R5 // Sequential next instruction

Instruction3: ...

Clock 1: [Instruction1 Fetch]

Clock 2: [Instruction1 Decode] [Instruction2 Fetch] ← Don't know if this is correct yet!

Clock 3: [Instruction1 Execute] [Instruction2 Decode] ← Branch decision happens here

Solution: Branch Prediction. CPU guesses "probably won't branch" and speculatively fetches instructions. If wrong, flush the pipeline and restart. Modern CPUs predict with 95%+ accuracy.

3. Structural HazardInsufficient hardware resources (memory bus, ALU, etc.) prevent simultaneous execution. Example: Instruction1 reads memory while Instruction3 tries writing memory - collision.

Solution: Harvard Architecture (separate instruction and data memory) or multi-port memory.

Pipelining wasn't enough, so modern CPUs went further:

Superscalar: Multiple pipelines fetching several instructions per clock. Intel i9 processes 4-6 instructions simultaneously.

Out-of-Order Execution: Maintain instruction order semantics but execute "whatever's ready first." If Instruction2 waits for data, execute Instruction3 first and do Instruction2 later.

Original order:

1. LOAD R1, [100] // Memory read - slow

2. ADD R2, R1, R3 // Needs R1 (must wait)

3. MUL R4, R5, R6 // Independent of R1

Out-of-order execution:

1. LOAD R1, [100] starts

3. MUL R4, R5, R6 executes (finishes first)

2. ADD R2, R1, R3 executes (after LOAD completes)

→ Total execution time reduced

All these techniques exist to spin the Fetch-Decode-Execute cycle as fast as possible.

The instruction cycle doesn't always flow smoothly. Interrupts force the CPU to stop current work and handle something else.

Normal flow:

Fetch → Decode → Execute → Fetch → Decode → Execute ...

Interrupt occurs:

Fetch → Decode → Execute → [Interrupt!] →

→ Save current state (PC, registers, etc.)

→ Execute interrupt handler (Fetch-Decode-Execute)

→ Restore original state

→ Fetch → Decode → Execute ... (resume)

Interrupts are usually checked at the end of Execute stage. Keyboard input, timer, disk I/O completion trigger interrupts. Without this, the CPU would be oblivious to the outside world.

Early in my startup days, I accidentally deployed code with an infinite loop. while (true) without a break condition. Server CPU hit 100%, all other requests froze.

At the time, I just thought "oops, my mistake." But after studying instruction cycles, I understood why the CPU suffered so much.

The CPU doesn't judge "this is pointless." It just repeats Fetch-Decode-Execute on whatever instructions it's given. If while (true) contains i++, the CPU repeats "read i → add 1 → write i" billions of times per second.

Pipelining, branch prediction, superscalar - every optimization technique gets mobilized to do meaningless work as fast as possible. Like a treadmill at max speed while you go nowhere.

The magic of modern CPUs.

if (a > 0), the CPU guesses "It'll probably be true" and executes the next instructions before knowing the actual result.This keeps the pipeline full. However, this optimization caused the famous Spectre & Meltdown vulnerabilities. Even if the CPU rolls back a wrong guess, traces remain in the Cache, which hackers exploited to read protected memory.

The best way to understand pipelining is doing laundry.

No Pipeline (Sequential):

Pipeline (Parallel):

The CPU is a giant laundromat. The Washer (Fetch), Dryer (Decode), and Iron (Execute) must never be idle.

How we design the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) fundamentally affects cycle efficiency.

CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer, e.g., Intel x86):

MULT a, b (Load a & b from memory, multiply, store result).RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer, e.g., ARM, RISC-V):

LOAD a, LOAD b, PROD a, b, STORE a.Modern x86 CPUs are hybrids: they take CISC instructions and translate them internally into simple Micro-ops that behave like RISC instructions.