CPU vs GPU: 아인슈타인 1명 vs 초등학생 10,000명 (완전정복)

AI와 딥러닝은 왜 CPU를 버리고 GPU를 선택했을까요? ALU 구조 차이부터 CUDA 메모리 계층, 그래픽 API(Vulakn/DirectX), 그리고 생성형 AI의 원리까지 하드웨어 가속의 모든 것을 다룹니다.

AI와 딥러닝은 왜 CPU를 버리고 GPU를 선택했을까요? ALU 구조 차이부터 CUDA 메모리 계층, 그래픽 API(Vulakn/DirectX), 그리고 생성형 AI의 원리까지 하드웨어 가속의 모든 것을 다룹니다.

맥북 배터리는 왜 오래 갈까? 서버 비용을 줄이려면 AWS Graviton을 써야 할까? 복잡함(CISC)과 단순함(RISC)의 철학적 차이를 정리해봤습니다.

AI 시대의 금광, 엔비디아 GPU. 도대체 게임용 그래픽카드로 왜 AI를 돌리는 걸까? 단순 노동자(CUDA)와 행렬 계산 천재(Tensor)의 차이로 파헤쳐봤습니다.

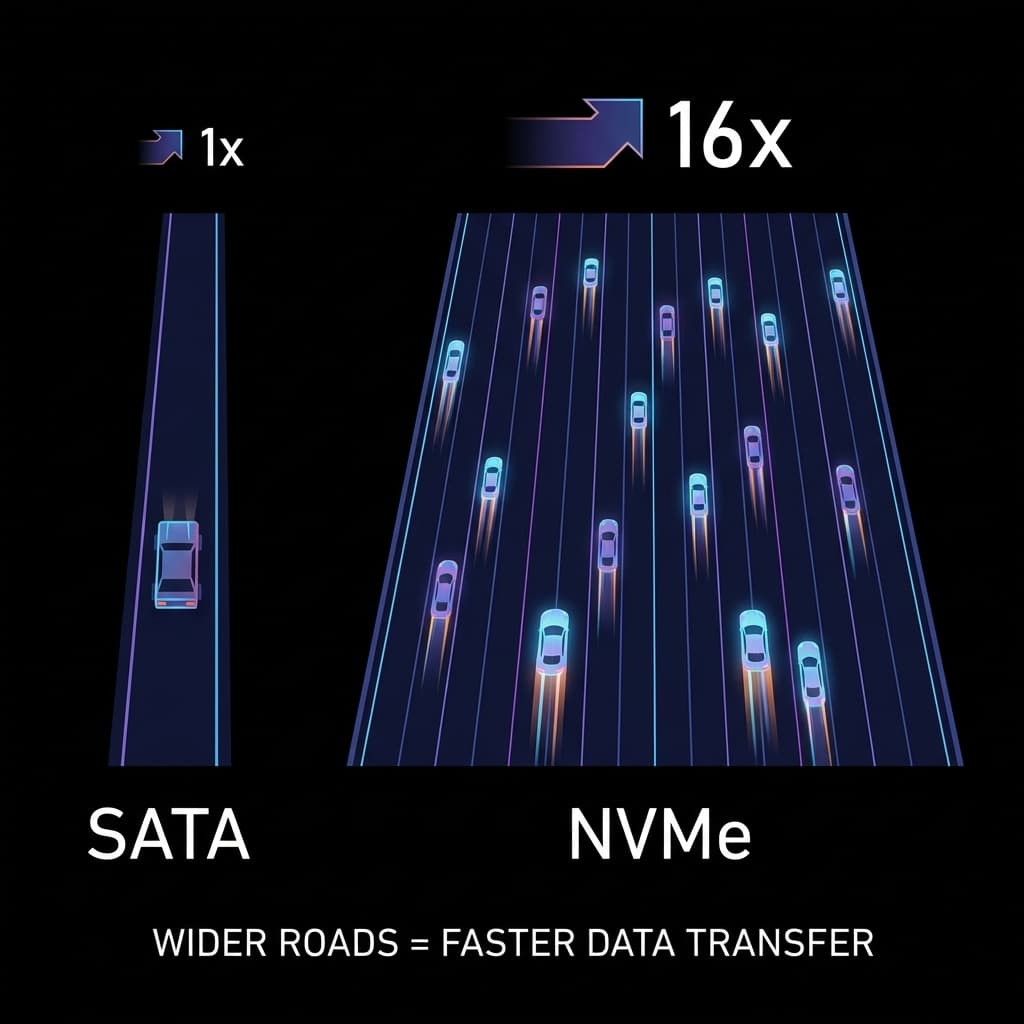

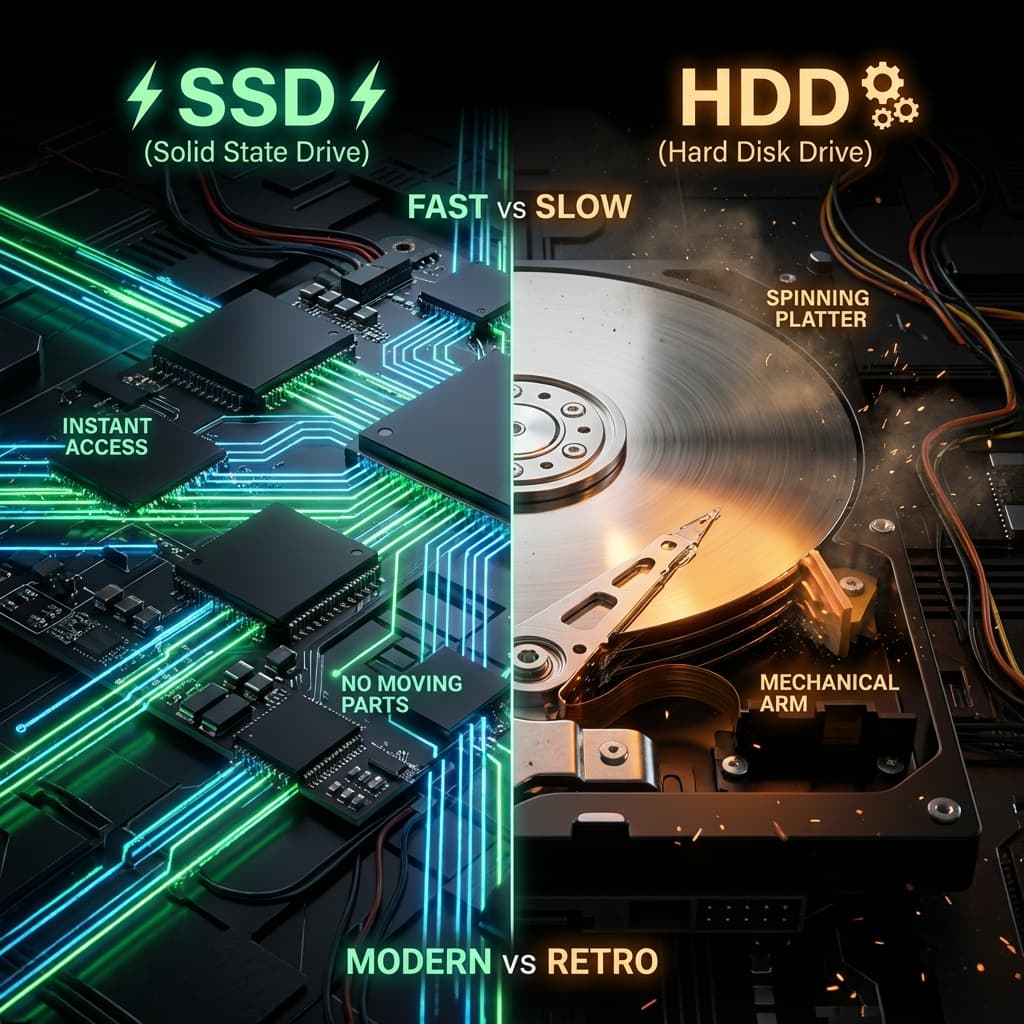

빠른 SSD를 샀는데 왜 느릴까요? 1차선 시골길(SATA)과 16차선 고속도로(NVMe). 인터페이스가 성능의 병목이 되는 이유.

LP판과 USB. 물리적으로 회전하는 판(Disc)이 왜 느릴 수밖에 없는지, 그리고 SSD가 어떻게 서버의 처리량을 100배로 만들었는지 파헤쳐봤습니다.

처음 딥러닝에 입문했을 때 황당한 경험을 했다. 큰맘 먹고 산 i9 CPU 노트북으로 모델 학습을 돌려봤다. CPU가 컴퓨터의 두뇌니까, 최고급 모델이면 당연히 빠를 거라 생각했다. 그런데 예상 소요 시간이 "720시간"이라고 떴다. 한 달을 기다리란 말인가?

당황해서 연구실 선배에게 물어봤더니, 선배가 웃으며 서버를 하나 빌려줬다. 그 서버에 달린 건 CPU가 아니라 게임용 그래픽 카드인 GPU였다. 놀랍게도 내 노트북에서 한 달 걸린다던 작업이 그 서버에서는 30분 만에 끝났다.

그때의 충격을 아직도 기억한다. 게임하라고 만든 그래픽 카드가 왜 미적분 수학 문제를 CPU보다 수천 배 잘 푸는 걸까? 이 의문을 풀기 위해 몇 주를 하드웨어 문서와 씨름했고, 결국 이거였다 — "빠른 천재 1명"과 "느린 병사 만 명"의 차이.

이 글은 그때 내가 받아들였던 깨달음을 정리해본다.

처음엔 억울했다. i9 프로세서는 벤치마크에서 항상 최상위권이었고, 단일 코어 성능도 압도적이었으니까. 그런데 딥러닝 모델 학습에선 완전히 무력했다. 도대체 뭐가 문제였을까?

문제는 "무엇을 빨리 하느냐"였다. CPU는 복잡한 한 문제를 빠르게 해결하도록 설계되었다. 컴파일러 최적화, 분기 예측, 비순차 실행(Out-of-Order Execution), 거대한 캐시 메모리 — 이 모든 게 "한 번에 한 작업을 초고속으로" 처리하기 위한 장치들이다.

반면 딥러닝 학습은 단순한 연산을 몇억 번 반복하는 작업이다. 행렬 곱셈이 전부다. 곱하고, 더하고, 곱하고, 더하고... 이런 작업엔 천재 한 명보다 평범한 사람 만 명이 훨씬 효율적이다.

이 깨달음이 와닿았던 순간, 컴퓨터 아키텍처에 대한 내 시각이 완전히 바뀌었다.

이 비유를 처음 들었을 때 모든 게 명확해졌다.

처음엔 이해가 안 갔다. 게임이랑 인공지능이 무슨 공통점이 있다고? 그런데 이해했다 — 둘 다 "단순 막노동"이라는 사실을.

4K 모니터는 약 830만 개의 픽셀이 있다. 각 픽셀의 RGB 값을 바꾸는 건 복잡한 미적분이 아니다. 그냥 R += 10, G -= 5 같은 단순 연산의 반복이다. AI의 행렬 곱셈도 마찬가지다. 수백만 번의 곱셈과 덧셈을 반복하는 일.

이런 "단순 반복 작업"에는 비싼 연봉의 아인슈타인(CPU)보다, 최저시급 알바생 만 명(GPU)이 훨씬 효율적이다. 이 비유가 완벽하게 와닿았다.

GPU가 어떻게 여기까지 왔는지 타임라인을 정리해본다.

CPU가 하던 3D 연산을 처음으로 도와주는 보조 카드 등장. 오직 게임(퀘이크, 툼레이더)만을 위해 존재했다. 삼각형 그리기 원툴.

최초로 "Transform & Lighting" 과정을 하드웨어가 처리했다. 젠슨 황이 처음으로 GPU라는 단어를 마케팅에 사용했다. 이때까지만 해도 그래픽 전용 카드였다.

최초의 통합 쉐이더 아키텍처 (Unified Shader)가 등장했다. 더 중요한 건 CUDA의 출시였다.

CUDA는 "그래픽 말고 C언어로 수학 계산도 시켜보자"는 발상에서 나왔다. 이게 GPGPU (General Purpose GPU)의 시작이었고, 과학자들이 GPU를 슈퍼컴퓨터처럼 쓰기 시작했다. 이 시점이 내가 정리해본다면 GPU의 진정한 전환점이었다.

제프리 힌튼 교수팀이 GPU 2장으로 딥러닝 모델을 학습시켜 이미지 인식 대회를 압도적으로 이겼다. 이 사건 이후 "GPU가 AI에 필수"라는 인식이 전 세계로 퍼졌다. 나도 이 논문 때문에 GPU를 공부하기 시작했다.

빛의 경로를 추적하는 RT 코어와 AI 연산을 위한 Tensor 코어가 탑재됐다. 하드웨어 가속이 세분화되기 시작했다. 게임과 AI가 각자의 전용 코어를 갖게 된 시점이다.

게임? 알 바 아님. 오직 AI 학습만을 위해 설계된 데이터센터용 GPU. 가격이 수천만 원을 호가한다. 이제 GPU는 그래픽이 아니라 AI의 심장이 됐다.

이 타임라인을 정리하면서 이해했다 — GPU는 "진화"한 게 아니라 "재탄생"한 거였다.

왜 갑자기 병렬 처리가 중요해졌을까? 이 질문에 답하려면 무어의 법칙을 이해해야 한다.

인텔의 창업자 고든 무어는 "반도체 성능은 18개월마다 2배가 된다"고 했다. 실제로 1970년대부터 2000년대 초반까지 이 법칙은 정확히 맞아떨어졌다. CPU 클럭 속도는 계속 올라갔다.

하지만 2005년쯤부터 CPU 클럭 속도의 향상이 멈췄다. 물리적 한계 — 특히 발열 문제(Thermal Wall) — 때문이었다. 클럭을 더 올리면 칩이 녹아버린다.

CPU를 더 빠르게 만들 수 없다면? 여러 개 붙이자. 이게 멀티코어 시대의 시작이었다. 그리고 GPU는 이 개념을 극단까지 밀어붙였다.

이제 둘의 설계 철학 차이가 명확해졌다.

CPU: Latency 지향 (Low Latency)이 차이를 받아들였을 때, CPU와 GPU가 왜 같은 문제에서도 성능 차이가 수백 배 나는지 완전히 이해됐다.

코드로 보면 더 명확하다.

기본적으로 명령어 하나가 데이터 하나를 처리한다. 물론 현대 CPU도 AVX 같은 SIMD 명령어가 있지만, GPU에 비하면 제한적이다.

# CPU 스타일 - 순차적 실행 (Sequential)

import time

def cpu_add(n):

a = [1] * n

b = [2] * n

c = [0] * n

# 100만 번의 루프를 혼자서 돎

start = time.time()

for i in range(n):

c[i] = a[i] + b[i]

print(f"CPU 처리 시간: {time.time() - start}초")

# n이 1,000,000이면 커피 마시고 와야 함

cpu_add(1_000_000)

이 코드를 처음 돌렸을 때 생각했다. "이게 뭐가 느린 거지?" 하지만 GPU 버전을 보고 나서 충격을 받았다.

명령어 하나("더해라!")를 내리면, 수천 개의 코어가 동시에 각자의 데이터를 잡고 실행한다.

// GPU 스타일: 병렬 실행 (Parallel) - CUDA C++

// __global__ 키워드: GPU에서 실행되는 함수(Kernel)임을 명시

__global__ void gpu_add(int *a, int *b, int *c, int n) {

// threadIdx.x: 현재 스레드의 번호 (나는 몇 번째인가?)

// blockIdx.x: 현재 스레드 블록의 번호

// blockDim.x: 한 블록에 몇 개의 스레드가 있는가?

// 이 공식으로 나의 고유 ID를 계산 (전체 운동장에서 내 위치)

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// 내 담당 구역만 처리 (if문으로 범위 체크)

if (i < n) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

/*

CPU: 루프 돌며 하나씩 처리 (For-Loop)

GPU: "야! 너네 1번부터 100만 번까지 각자 위치로!" -> "실시!" (동시 실행)

이것이 SIMT (Single Instruction Multiple Threads) 모델이다.

*/

// 호스트 코드 (CPU에서 실행)

int main() {

int n = 1000000;

// GPU 메모리 할당 및 데이터 복사

// (생략)

// Kernel 실행: 1000개의 블록, 블록당 1024개의 스레드

int threadsPerBlock = 1024;

int blocksPerGrid = (n + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

gpu_add<<<blocksPerGrid, threadsPerBlock>>>(d_a, d_b, d_c, n);

// 1,024,000개의 스레드가 동시에 실행됨

// 루프 없음. 폭격.

}

이 코드를 처음 이해했을 때의 쾌감을 잊을 수 없다. 루프가 없다. 모든 스레드가 동시에 실행된다. 이게 바로 GPU의 본질이었다.

GPU 프로그래밍에서 가장 어려운 부분이 메모리 관리다. 이걸 이해하는 데 꽤 오래 걸렸다.

GPU도 CPU처럼 메모리 계층이 있다.

CUDA 최적화의 핵심은 "느려터진 Global Memory 접근을 줄이고, Shared Memory를 활용하는 것"이다. 이것이 타일링(Tiling) 기법이다.

// Shared Memory를 활용한 행렬 곱셈 (간소화 버전)

__global__ void matmul_shared(float *A, float *B, float *C, int N) {

// Shared Memory 선언 (블록 내 모든 스레드가 공유)

__shared__ float As[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

__shared__ float Bs[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

// Global Memory → Shared Memory로 데이터 복사

As[ty][tx] = A[row * N + (tile * TILE_SIZE + tx)];

Bs[ty][tx] = B[(tile * TILE_SIZE + ty) * N + col];

// 동기화: 모든 스레드가 데이터 복사를 끝낼 때까지 대기

__syncthreads();

// Shared Memory에서 계산 (Global Memory보다 100배 빠름)

for (int k = 0; k < TILE_SIZE; k++) {

sum += As[ty][k] * Bs[k][tx];

}

// 다시 동기화

__syncthreads();

}

이 패턴을 이해했을 때, "아, GPU 프로그래밍은 결국 메모리 게임이구나"라고 받아들였다.

GPU에게 일을 시키려면 언어(API)가 필요하다. 각 API마다 철학이 다르다.

옛날엔 GPU로 계산하려면 "이 숫자를 픽셀 색깔인 척" 속여서 그림을 그려야 했다. 눈물 나는 똥꼬쇼였다.

하지만 Compute Shader가 나오면서, 그래픽 파이프라인과 상관없이 GPU를 순수 계산기처럼 쓸 수 있게 됐다. 유니티(Unity)나 언리얼 엔진에서도 이 기능을 써서 수만 마리의 물고기 떼(Flocking) 시뮬레이션을 돌린다.

이 부분을 정리해본다 — GPU는 이제 그래픽이 아니라 범용 병렬 컴퓨터다.

Stable Diffusion 같은 AI 그림 생성은 어떻게 돌아갈까? 이걸 이해하는 데 꽤 시간이 걸렸다.

CPU로 돌리면 한 장 뽑는 데 10분 걸리지만, GPU는 5초면 끝난다.

RTX 시리즈의 Tensor Core는 FP16(반정밀도) 행렬 곱셈에 특화됐다. AI 학습과 추론에선 32비트 정밀도가 필요 없다. 16비트면 충분하다. Tensor Core는 이걸 하드웨어 레벨에서 가속한다.

# Stable Diffusion의 핵심 루프 (간소화)

for step in range(50): # 50번 반복

# U-Net Forward Pass

noise_pred = unet(latent, timestep, text_embedding)

# 노이즈 예측값만큼 빼기

latent = latent - noise_pred * scheduler_scale

# 각 스텝마다 수십억 번의 곱셈/덧셈 발생

# GPU 없으면 불가능

이것이 FP16과 Tensor Core의 힘이다. 정리해본다 — 생성형 AI는 GPU 없이는 불가능했을 것이다.

"왜 똑같은 칩인데 쿼드로는 5배 비싼가요?" 이 질문을 처음 받았을 때 나도 몰랐다. 알아보니 이유가 있었다.

결론: 돈 버는 도구는 비싸다. 취미로 쓰는 건 싸다. 시장의 이치다.

이제 실제로 어떻게 선택할지 정리해본다.

if-else 지옥)예시: 웹 서버, 데이터베이스 쿼리, OS 실행

예시: AI 학습/추론, 비디오 인코딩, 물리 시뮬레이션

# Bad: GPU로 짧은 루프 돌리기 (오버헤드만 큼)

for i in range(100): # 너무 작음

gpu_kernel(data[i])

# Good: CPU로 처리

for i in range(100):

result = simple_calc(data[i])

# Good: GPU로 긴 루프 돌리기

gpu_kernel(data) # 한 번에 100만 개 처리

이해했다 — 도구의 선택은 작업의 성격에 달려 있다.

"CPU가 좋나요, GPU가 좋나요?"는 우문이다. "페라리가 좋나요, 버스가 좋나요?"와 같은 질문이니까.

데이트하러 갈 땐 페라리(CPU)가 좋고, 수학여행 갈 땐 버스(GPU)가 좋다.

개발자로서 여러분은 내 코드가 어떤 성격인지 파악해야 한다.

컴퓨터는 혼자 일하지 않는다. 천재 교수(CPU)와 수만 명의 제자들(GPU)이 협업할 때, 비로소 최고의 성능이 나온다.

결국 이거였다 — 하드웨어는 도구일 뿐이고, 진짜 실력은 적재적소에 쓰는 능력이다.

| 특성 | CPU (Central Processing Unit) | GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) |

|---|---|---|

| 코어 수 | 적음 (4개 ~ 64개) | 엄청 많음 (수천 개 ~ 수만 개) |

| 코어 당 성능 | 매우 높음 (천재) | 낮음 (초등학생) |

| 핵심 목표 | Low Latency (빠른 응답) | High Throughput (대량 처리) |

| 제어 로직 | 복잡함 (분기 예측, OOO 실행) | 단순함 |

| 캐시 메모리 | 큼 (L1/L2/L3) | 작음 (공유 메모리 활용) |

| 명령어 구조 | SISD (or limited SIMD) | SIMT (Single Instruction Multiple Threads) |

| 특화 작업 | OS 실행, 웹 서버, 복잡한 로직 | 그래픽 렌더링, 딥러닝, 암호화폐 채굴 |

| 비유 | 페라리, 아인슈타인 | 버스, 초등학생 군단 |

| 가격 (소비자용) | 30만 원 ~ 200만 원 | 50만 원 ~ 300만 원 |

| 가격 (서버용) | 100만 원 ~ 1000만 원 | 500만 원 ~ 5000만 원 (H100) |

When I first tried deep learning, I made an expensive mistake. I bought a top-tier i9 laptop, thinking, "The CPU is the brain of the computer, so the best CPU must be the fastest."

I launched my first training job. The estimated time: 720 hours. A full month.

Confused and frustrated, I asked a senior researcher. He laughed and lent me a server. It had a gaming graphics card — a GPU. The same task that would've taken 30 days on my laptop finished in 30 minutes.

I was shocked. Why was a card designed for playing video games thousands of times better at math than my expensive CPU?

That question haunted me for weeks. I dug into hardware documentation, benchmark tests, and architecture papers. And then it clicked — the difference between "one genius" and "ten thousand workers."

This post is my attempt to share that revelation.

At first, I felt betrayed. My i9 processor was always at the top of benchmarks. Single-core performance? Unmatched. But when it came to deep learning, it was completely powerless.

What went wrong?

The problem wasn't speed. It was what kind of speed mattered.

CPUs are designed to solve one complex problem extremely fast. Compiler optimizations, branch prediction, out-of-order execution, massive caches — all these exist to handle one task at light speed.

But deep learning training is about repeating simple operations billions of times. Matrix multiplication. Multiply, add, multiply, add, multiply, add... For this kind of work, one genius is far less efficient than ten thousand average workers.

When I finally understood this, my entire view of computer architecture changed.

This analogy made everything clear.

At first, this confused me. What do video games and artificial intelligence have in common?

Then I realized — both are "simple, repetitive labor."

A 4K monitor has 8.3 million pixels. Changing each pixel's RGB value isn't rocket science. It's just simple arithmetic: R += 10, G -= 5, repeat 8 million times. AI's matrix multiplication is the same. Millions of multiplications and additions.

For this kind of "manual labor," 10,000 minimum-wage workers (GPU) are far more efficient than one high-salary genius (CPU).

This metaphor clicked for me perfectly.

How did GPUs get here? Let me trace the timeline.

The first 3D accelerator card. Could only draw triangles for games like Quake and Tomb Raider.

NVIDIA's Jensen Huang coined the term GPU for marketing. First hardware Transform & Lighting. Still just graphics.

First Unified Shader Architecture. More importantly, CUDA launched.

CUDA's pitch: "Let's use GPUs for math, not just graphics." This was the birth of GPGPU (General Purpose GPU). Scientists started using GPUs as supercomputers. In my view, this was the real turning point.

Geoffrey Hinton's team trained a deep learning model on 2 GPUs and crushed the ImageNet competition. After this, "GPUs are essential for AI" became gospel. I started studying GPUs because of this paper.

RT Cores for ray tracing and Tensor Cores for AI. Hardware acceleration became specialized. Games and AI each got dedicated cores.

Gaming? Irrelevant. Designed purely for AI training in data centers. Costs tens of thousands of dollars. GPUs are no longer graphics cards — they're AI engines.

When I mapped this timeline, I realized GPUs didn't just "evolve" — they were reborn.

Why did parallel processing suddenly matter?

To answer this, we need to understand Moore's Law.

Intel founder Gordon Moore predicted: "Semiconductor performance doubles every 18 months." From the 1970s to the early 2000s, this held true. CPU clock speeds kept rising.

But around 2005, CPU clock speeds stopped increasing. We hit a physical limit — the Thermal Wall. Push the clock higher, and the chip melts.

If we can't make CPUs faster, let's add more of them. This kicked off the multi-core era. GPUs took this concept to the extreme.

Now the design philosophies became crystal clear.

CPU: Latency-Oriented (Low Latency)Understanding this difference explained why CPUs and GPUs can have 100x performance differences on the same problem.

Code makes this even clearer.

One instruction processes one piece of data. Modern CPUs have SIMD extensions like AVX, but they're limited compared to GPUs.

# CPU Style: Sequential Execution

import time

def cpu_add(n):

a = [1] * n

b = [2] * n

c = [0] * n

# One loop running 1 million times

start = time.time()

for i in range(n):

c[i] = a[i] + b[i]

print(f"CPU Time: {time.time() - start}s")

# If n = 1,000,000, grab a coffee

cpu_add(1_000_000)

When I first ran this, I thought, "What's so slow about this?" Then I saw the GPU version.

One command ("ADD!") triggers thousands of cores simultaneously.

// GPU Style: Parallel Execution (CUDA C++)

// __global__: Function runs on GPU (Kernel)

__global__ void gpu_add(int *a, int *b, int *c, int n) {

// threadIdx.x: My thread number (which one am I?)

// blockIdx.x: My block number

// blockDim.x: How many threads per block?

// Calculate my unique ID (my position in the field)

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// Process only my assigned data

if (i < n) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

/*

CPU: Loop through one by one (For-Loop)

GPU: "Hey! Positions 1 through 1 million, GO!" (simultaneous execution)

This is the SIMT (Single Instruction Multiple Threads) model.

*/

// Host code (runs on CPU)

int main() {

int n = 1000000;

// GPU memory allocation and data transfer

// (omitted for brevity)

// Kernel launch: 1000 blocks, 1024 threads per block

int threadsPerBlock = 1024;

int blocksPerGrid = (n + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

gpu_add<<<blocksPerGrid, threadsPerBlock>>>(d_a, d_b, d_c, n);

// 1,024,000 threads execute simultaneously

// No loop. Bombardment.

}

When I finally grasped this code, the satisfaction was immense. No loop. All threads execute at once. This was GPU's essence.

The hardest part of GPU programming is memory management. It took me a while to understand this.

GPUs have a memory hierarchy like CPUs.

The core of CUDA optimization: "Minimize slow Global Memory access, maximize Shared Memory usage." This is called Tiling.

// Matrix multiplication using Shared Memory (simplified)

__global__ void matmul_shared(float *A, float *B, float *C, int N) {

// Declare Shared Memory (shared by all threads in block)

__shared__ float As[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

__shared__ float Bs[TILE_SIZE][TILE_SIZE];

// Copy data: Global Memory → Shared Memory

As[ty][tx] = A[row * N + (tile * TILE_SIZE + tx)];

Bs[ty][tx] = B[(tile * TILE_SIZE + ty) * N + col];

// Synchronize: Wait for all threads to finish copying

__syncthreads();

// Compute from Shared Memory (100x faster than Global)

for (int k = 0; k < TILE_SIZE; k++) {

sum += As[ty][k] * Bs[k][tx];

}

// Synchronize again

__syncthreads();

}

When I understood this pattern, I realized: "GPU programming is fundamentally a memory game."

To command a GPU, you need a language (API). Each has a different philosophy.

In the old days, to use GPUs for computation, you had to "pretend numbers were pixel colors" and draw fake images. It was ridiculous.

But Compute Shaders changed that. Now you can use GPUs as pure calculators, independent of the graphics pipeline. Unity and Unreal Engine use this for simulations like fish flocking (thousands of fish).

My takeaway: GPUs are no longer graphics cards — they're general-purpose parallel computers.

How do AI image generators like Stable Diffusion work? It took me a while to understand.

On a CPU, generating one image takes 10 minutes. On a GPU, it takes 5 seconds.

RTX series Tensor Cores specialize in FP16 (half-precision) matrix multiplication. For AI training and inference, 32-bit precision isn't necessary — 16-bit is enough. Tensor Cores accelerate this at the hardware level.

# Stable Diffusion's core loop (simplified)

for step in range(50): # 50 iterations

# U-Net Forward Pass

noise_pred = unet(latent, timestep, text_embedding)

# Subtract predicted noise

latent = latent - noise_pred * scheduler_scale

# Each step: billions of multiplications/additions

# Impossible without GPU

This is the power of FP16 and Tensor Cores. My conclusion: Generative AI would've been impossible without GPUs.

"Why is Quadro 5x more expensive than GeForce with the same chip?"

I didn't know either at first. But there are real reasons.

Conclusion: Tools that make money cost money. Hobby tools are cheap. Market logic.

Let me summarize when to choose each.

if-else hell)Examples: Web servers, database queries, OS operations

Examples: AI training/inference, video encoding, physics simulation

# Bad: Using GPU for short loops (overhead dominates)

for i in range(100): # Too small

gpu_kernel(data[i])

# Good: CPU for small tasks

for i in range(100):

result = simple_calc(data[i])

# Good: GPU for massive tasks

gpu_kernel(data) # Process 1 million items at once

I learned: Tool choice depends on task nature.

"Is CPU better or GPU better?" is a silly question. It's like asking "Is a Ferrari better or a bus better?"

For a date, take the Ferrari (CPU). For a school trip, take the bus (GPU).

As a developer, you need to understand your code's nature.

Computers don't work alone. When the genius professor (CPU) and ten thousand students (GPU) collaborate, peak performance emerges.

My final realization: Hardware is just a tool. True skill is knowing when to use which tool.