버스(Bus) 시스템: 메인보드의 고속도로와 4GB 램의 진실

CPU는 램에서 데이터를 어떻게 가져올까요? 우편 배달부(주소 버스)의 가방 크기가 메모리 용량을 결정합니다. 32비트 OS가 4GB밖에 못 썼던 이유, 그리고 PCIe가 GPU 성능에 미치는 영향을 파헤칩니다.

CPU는 램에서 데이터를 어떻게 가져올까요? 우편 배달부(주소 버스)의 가방 크기가 메모리 용량을 결정합니다. 32비트 OS가 4GB밖에 못 썼던 이유, 그리고 PCIe가 GPU 성능에 미치는 영향을 파헤칩니다.

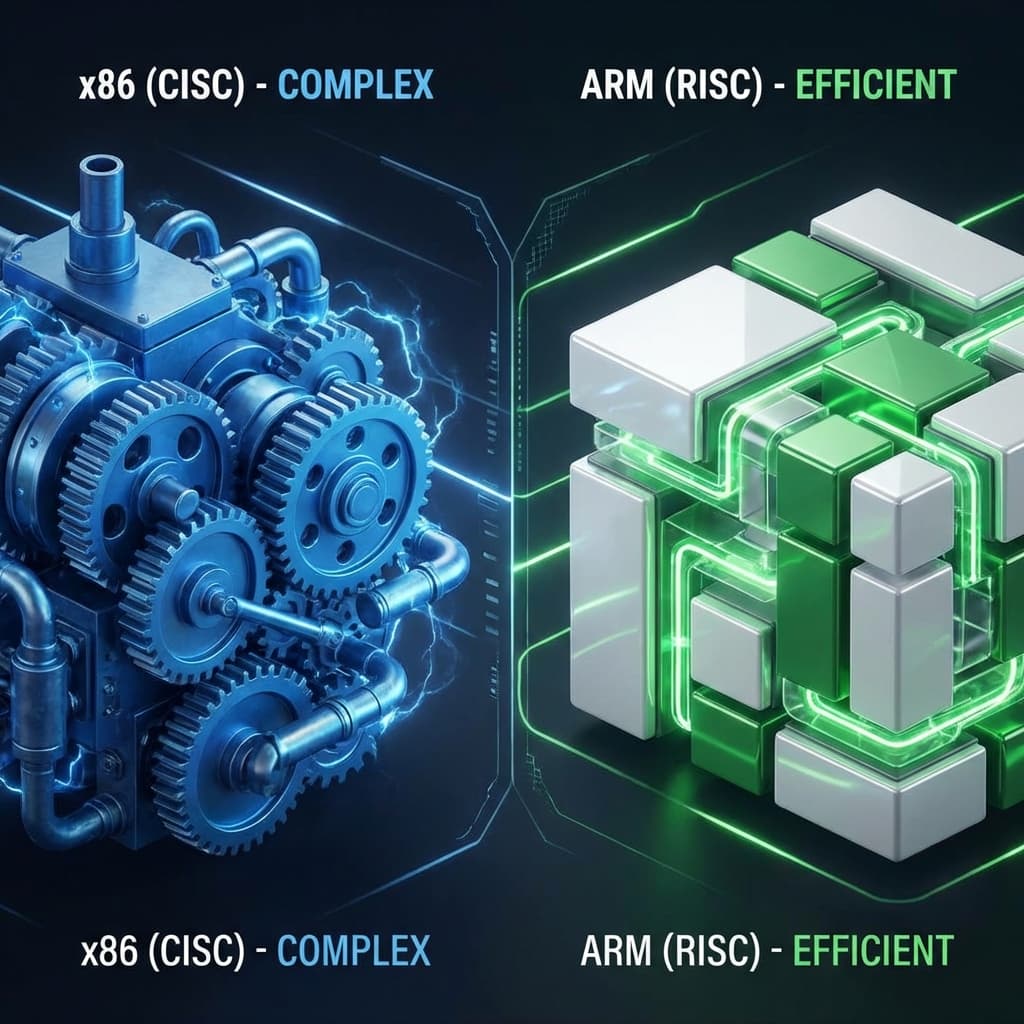

맥북 배터리는 왜 오래 갈까? 서버 비용을 줄이려면 AWS Graviton을 써야 할까? 복잡함(CISC)과 단순함(RISC)의 철학적 차이를 정리해봤습니다.

AI 시대의 금광, 엔비디아 GPU. 도대체 게임용 그래픽카드로 왜 AI를 돌리는 걸까? 단순 노동자(CUDA)와 행렬 계산 천재(Tensor)의 차이로 파헤쳐봤습니다.

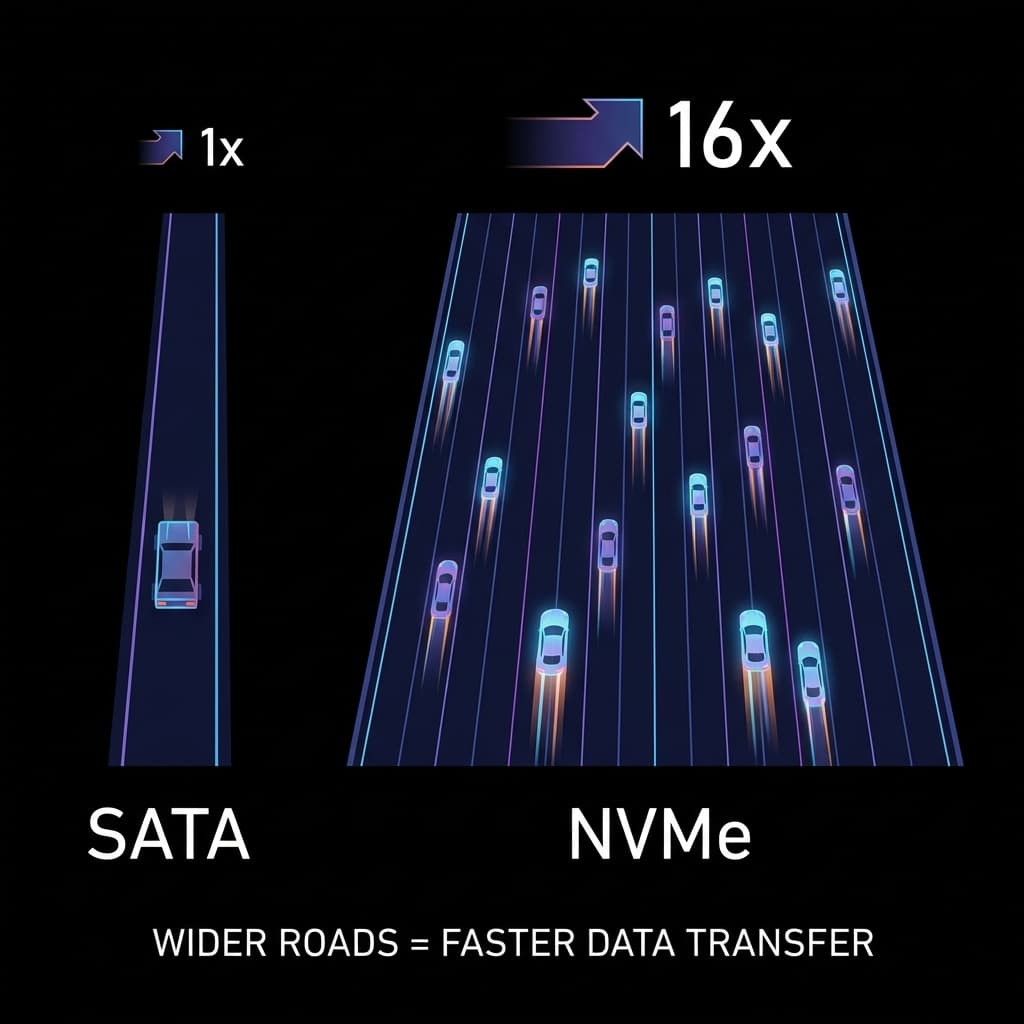

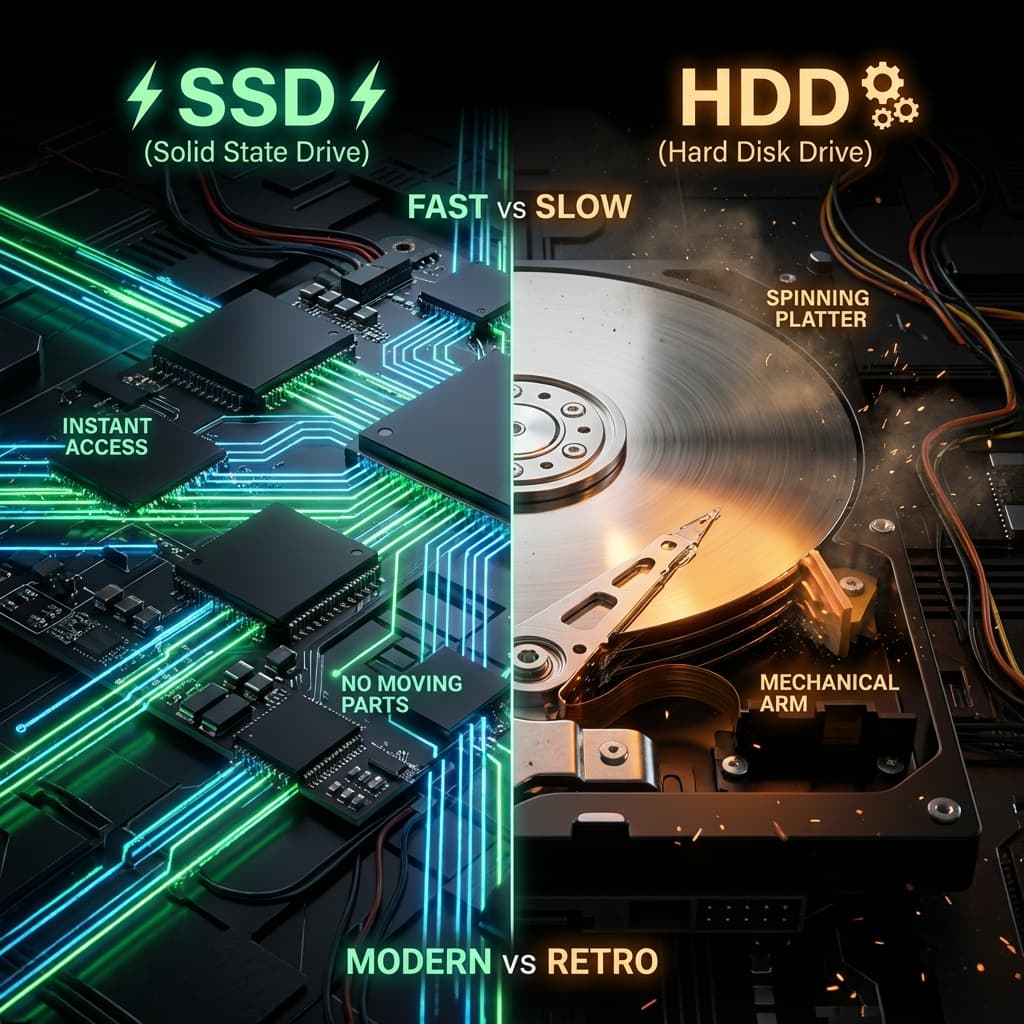

빠른 SSD를 샀는데 왜 느릴까요? 1차선 시골길(SATA)과 16차선 고속도로(NVMe). 인터페이스가 성능의 병목이 되는 이유.

LP판과 USB. 물리적으로 회전하는 판(Disc)이 왜 느릴 수밖에 없는지, 그리고 SSD가 어떻게 서버의 처리량을 100배로 만들었는지 파헤쳐봤습니다.

2010년 여름이었습니다. 제 대학 친구 재민이가 신나서 전화를 걸어왔습니다.

"야! 나 드디어 데스크톱 샀다! 용팔이 PC방 가서 사장님이랑 3시간 상담했어. 게임 돌리려면 램이 많아야 된다길래 8GB로 빵빵하게 넣었지!"

당시는 Core 2 Duo 시절이었고, 램 8GB면 엄청난 고급 사양이었습니다. 저도 4GB 쓰면서 부러워했던 기억이 납니다.

그런데 일주일 후, 재민이가 다시 전화를 걸어왔습니다. 이번엔 목소리가 풀죽어 있었습니다.

"야... 이상한데? 시스템 속성 들어가 봤더니 '설치된 RAM: 8.00GB (3.25GB 사용 가능)' 이러는데? PC방 사장이 사기친 거 아냐?"

저도 처음 듣는 현상이라 인터넷을 뒤졌습니다. 그리고 금방 원인을 찾았습니다.

저: "재민아, 너 혹시 Windows 7 32비트 깔았어?" 재민: "응? 그게 뭔데? 그냥 Windows 7이라고 해서 깔았는데..." 저: "64비트로 다시 깔아야 돼. 32비트는 램을 4GB밖에 못 써." 재민: "32비트가 뭔데? 숫자가 작으면 뭐가 달라지는데? 그리고 왜 4GB? 왜 5GB는 안 되고?"

저도 당시에는 "그냥 그렇다더라"는 수준으로만 알고 있었습니다. 정확한 이유를 몰랐죠. 그냥 "32비트는 옛날 거니까" 정도로만 이해하고 있었습니다.

이 의문은 2년 후, 컴퓨터공학과 2학년 "컴퓨터 구조" 수업에서 비로소 풀렸습니다. 교수님이 칠판에 딱 한 줄을 적었을 때, 머리를 망치로 맞은 듯한 충격이 왔습니다.

"Address Bus Width = 32 bits → 2³² = 4,294,967,296 bytes = 4GB"아, 주소가 32비트구나! 결국 이거였다.

비밀은 버스(Bus) 시스템에 있었습니다.

처음 "버스 시스템"이라는 용어를 들었을 때 저는 진짜 혼란스러웠습니다.

"CPU Bus", "System Bus", "Front-side Bus"... 뭔가 교통수단 얘기를 하는 건가? 메인보드 안에 작은 차들이 다니나? 당시 제 머릿속은 진짜 이런 상상으로 가득했습니다.

Wikipedia를 찾아봤더니 "A bus is a communication system that transfers data between components inside a computer"라고 나옵니다. 번역하면 "버스는 컴퓨터 내부 컴포넌트 간 데이터를 전송하는 통신 시스템"이라는데, 솔직히 이것만 봐서는 여전히 와닿지 않았습니다.

그런데 수업 시간에 교수님이 비유를 들어주셨습니다.

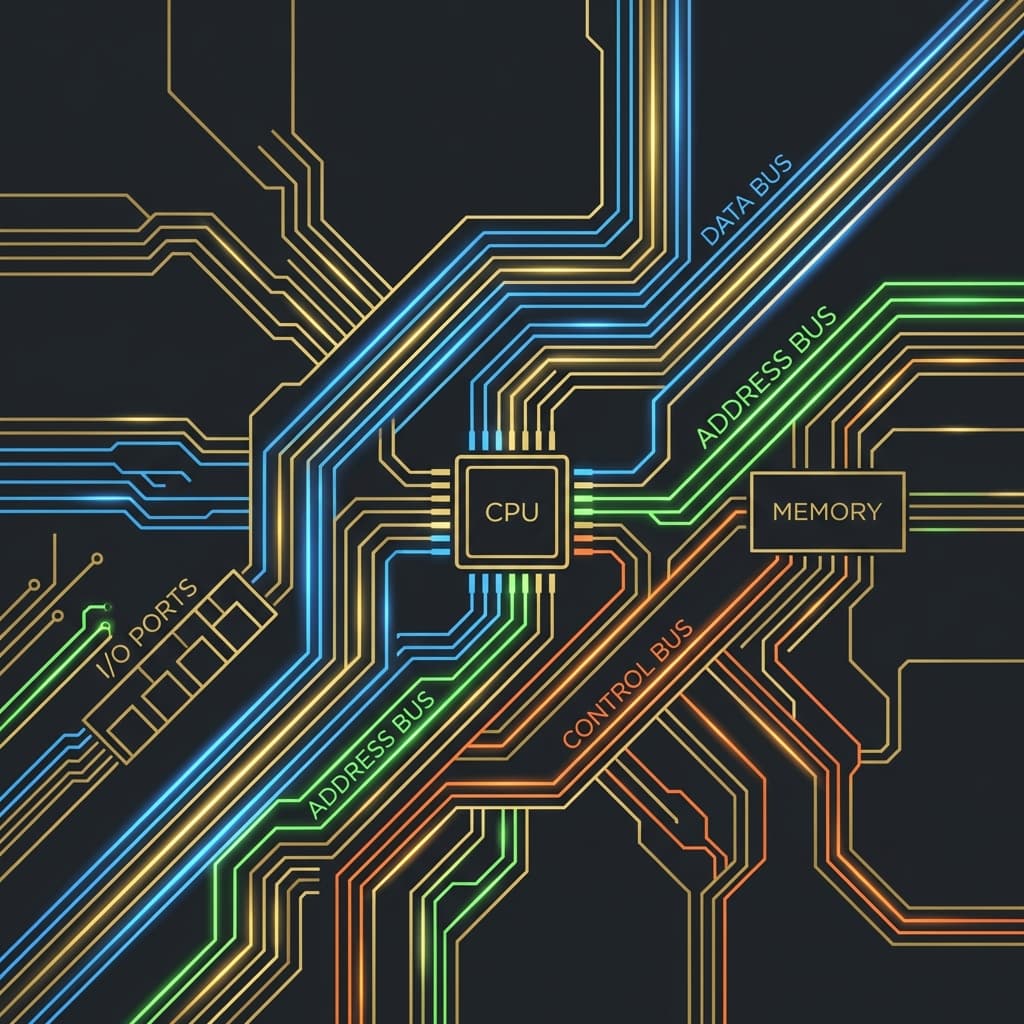

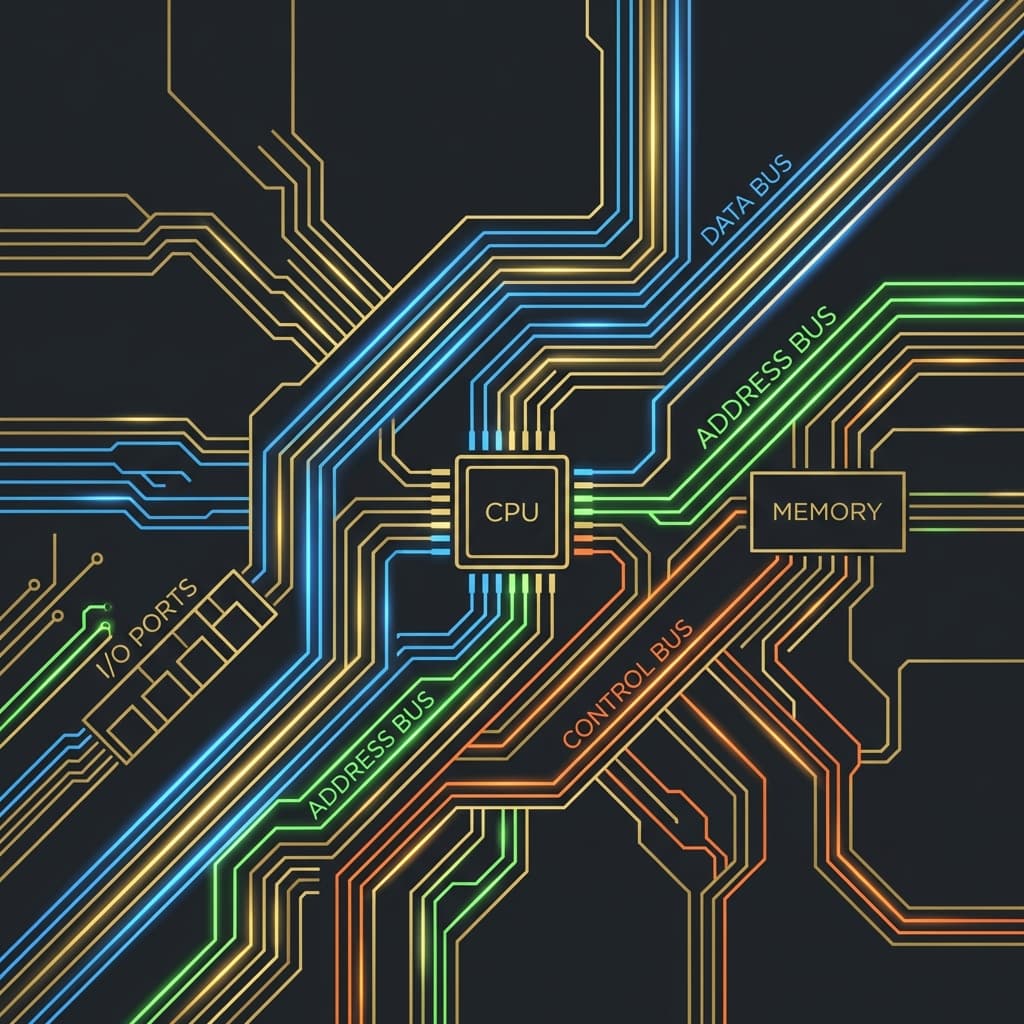

"너희들이 집에서 학교까지 오는 걸 생각해봐. 도로가 있고, 차가 다니지? 컴퓨터도 똑같아. CPU(집)에서 메모리(학교)까지 데이터(사람)가 이동하려면 전기 신호가 다니는 물리적인 선이 필요해. 그게 버스야. 메인보드를 자세히 보면 금색 선들이 촘촘하게 박혀있잖아? 그게 다 버스 라인이야."

아, 이제 이해했다!

버스는 대중교통이 아니라 데이터가 다니는 물리적인 도로(전기 회로)였습니다. 그리고 그 도로의 폭(bit width), 속도(clock frequency), 차선 개수(lanes)에 따라 컴퓨터 성능이 달라진다는 것도 받아들였습니다.

다시 재민이의 8GB 램 문제로 돌아가 봅시다.

교수님이 칠판에 이걸 적었을 때 비로소 퍼즐이 맞춰졌습니다.

주소 버스(Address Bus) = 32 bits

→ 표현 가능한 주소 개수 = 2^32 = 4,294,967,296

→ 각 주소는 1바이트를 가리킴

→ 총 4,294,967,296 bytes = 4GB

와닿았다!

메모리의 각 바이트는 고유한 주소 번호를 가집니다. 마치 아파트 호수처럼요. "101호", "102호", "103호"... 이렇게 번호를 부여하는데, 32비트 체계에서는 숫자를 최대 약 43억 개까지밖에 만들 수 없습니다.

즉, 43억 번째 주소(4GB) 너머에 있는 메모리는? CPU가 그곳을 부를 번호가 없어서 못 씁니다.

실제 물리적으로는 8GB 램이 꽂혀 있어도, CPU 입장에서는 "5GB 위치야, 데이터 줘봐" 라고 말할 방법이 없는 겁니다. 주소 체계에 그 번호가 없으니까요.

이건 마치 우편 배달부가 4자리 우편번호만 쓸 수 있는데 10000번지 이상의 주소를 배달하려는 것과 같습니다. 주소를 쓸 공간이 부족해서 물리적으로 불가능한 거죠.

반면 64비트 시스템은?

2^64 = 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 bytes

≈ 18 Exabytes (엑사바이트)

= 18,000,000 TB

사실상 무한대입니다. 우리가 살아있는 동안 64비트 주소 공간을 다 쓸 일은 없을 겁니다. (현존하는 슈퍼컴퓨터도 페타바이트 수준)

이제 재민이에게 전화를 걸어 자신있게 설명해줄 수 있게 됐습니다.

"야, 32비트 OS는 주소를 32자리 2진수로밖에 못 써. 그래서 표현 가능한 주소가 2의 32승인 43억 개야. 43억 바이트가 4GB지. 네 램이 8GB여도 나머지 4GB는 주소 번호 자체가 존재하지 않아서 못 쓰는 거야. 64비트로 다시 깔아."

버스가 뭔지는 이제 알겠는데, 버스가 하나만 있는 게 아니었습니다. 교수님이 그린 CPU-Memory 구조도를 보니 선이 세 종류로 나뉘어 있었습니다.

역할: "어디(Where)"를 지정합니다.

이걸 우편 배달 시스템으로 비유하면 딱 와닿습니다.

CPU는 우편 배달부입니다. 메모리는 거대한 아파트 단지(43억 세대)입니다. CPU가 "101동 502호에 있는 데이터 가져와줘" 라고 요청하려면 주소를 말해야 합니다.

특징:

실제 계산 예시:

# 주소 버스 폭에 따른 최대 메모리 계산

def max_memory(address_bits):

max_addresses = 2 ** address_bits

max_bytes = max_addresses # 1 address = 1 byte

max_GB = max_bytes / (1024 ** 3)

return max_GB

print(f"16-bit: {max_memory(16):.6f} GB") # 0.000061 GB = 64KB

print(f"32-bit: {max_memory(32):.6f} GB") # 4 GB

print(f"64-bit: {max_memory(64):.0f} GB") # 17,179,869,184 GB

출력:

16-bit: 0.000061 GB

32-bit: 4.000000 GB

64-bit: 17179869184 GB

이제 재민이의 8GB 램 사건이 완벽히 정리됐습니다.

역할: "무엇(What)"을 실어 나릅니다.

주소 버스가 "어디로 갈지" 정했으면, 이제 실제 데이터를 옮겨야겠죠. 데이터 버스는 그 화물 트럭입니다.

같은 클럭 속도라면 64비트가 이론상 2배 빠릅니다. 한 번 왕복할 때 2배로 많이 싣고 오니까요.

특징:

실제 대역폭 계산 예시:

# 버스 대역폭 계산 공식

# Bandwidth (MB/s) = (Bus Width in bits / 8) × Clock Speed (MHz) × Transfer Rate

def bus_bandwidth(bus_width_bits, clock_mhz, transfers_per_clock=1):

bus_width_bytes = bus_width_bits / 8

bandwidth_mb_per_sec = bus_width_bytes * clock_mhz * transfers_per_clock

return bandwidth_mb_per_sec

# 예시 1 - DDR4-3200 메모리 (64-bit bus, 3200MHz, DDR이므로 2회 전송)

ddr4_bandwidth = bus_bandwidth(64, 3200, 2)

print(f"DDR4-3200: {ddr4_bandwidth:,.0f} MB/s = {ddr4_bandwidth/1024:.1f} GB/s")

# 예시 2 - 32-bit 시스템에서 800MHz 메모리

old_bandwidth = bus_bandwidth(32, 800, 2)

print(f"32-bit 800MHz DDR: {old_bandwidth:,.0f} MB/s = {old_bandwidth/1024:.1f} GB/s")

출력:

DDR4-3200: 51,200 MB/s = 50.0 GB/s

32-bit 800MHz DDR: 6,400 MB/s = 6.2 GB/s

이제 이해했다. 64비트 시스템이 빠른 이유가 주소 공간뿐만 아니라 한 번에 데이터를 2배로 많이 나를 수 있기 때문이라는 것을요.

역할: "동작(Action)"을 지시합니다.

주소(어디)와 데이터(무엇)가 정해졌으면, 이제 "언제", "어떻게" 할지를 정해야 합니다.

제어 버스는 다음과 같은 신호를 보냅니다:

특징:

비유하자면 교통 신호등입니다. 빨간불(Wait), 초록불(Go), 좌회전 신호(Write), 직진 신호(Read)... 이런 걸 제어합니다.

우리가 쓰는 모든 컴퓨터는 폰 노이만 구조(Von Neumann Architecture)입니다.

핵심 개념: CPU와 메모리가 물리적으로 분리되어 있고, 하나의 버스를 공유한다.

이게 왜 문제일까요?

상상해보세요. CPU는 Ferrari F8입니다. 최고속도 시속 340km. 하지만 CPU와 메모리를 연결하는 도로는 편도 1차선 꽉 막힌 고속도로입니다.

아무리 Ferrari가 빨라도 앞차가 막히면 속도를 낼 수 없습니다. 이게 바로 폰 노이만 병목(Von Neumann Bottleneck)입니다.

실제 숫자로 보면 더 충격적입니다.

| 구분 | Latency (대기 시간) | CPU 클럭 환산 |

|---|---|---|

| L1 Cache (CPU 내장) | ~1 ns | 약 4 클럭 |

| L2 Cache | ~3 ns | 약 12 클럭 |

| L3 Cache | ~12 ns | 약 40 클럭 |

| DDR4 RAM | ~100 ns | 약 300 클럭! |

| NVMe SSD | ~100,000 ns | 약 300,000 클럭 |

즉, CPU가 메인 메모리(RAM)에서 데이터를 가져오려고 하면 약 300 클럭 사이클을 기다려야 합니다.

3GHz CPU라면 1초에 30억 번의 명령을 실행할 수 있는데, 300 클럭을 기다린다는 건 그 시간에 300개의 명령을 더 실행할 수 있었다는 뜻입니다.

정리해본다면, 폰 노이만 병목은 다음과 같습니다:

"CPU(계산 능력)의 발전 속도 >> 메모리(데이터 공급) 속도 발전"

결과: CPU가 계산은 다 끝냈는데, 다음 데이터를 기다리며 멍 때림.

이 문제를 해결하기 위해 하드웨어 엔지니어들이 수십 년간 싸워왔습니다.

① 캐시 메모리 (L1, L2, L3 Cache)CPU 안에 작은 메모리를 박아넣습니다. "자주 쓰는 데이터는 가까이 두자."

클럭 신호의 상승 엣지(Rising Edge)와 하강 엣지(Falling Edge) 양쪽에서 데이터를 전송합니다. 한 클럭당 2번 전송하니 속도가 2배가 됩니다.

③ 다중 채널 메모리 (Dual/Quad Channel)고속도로 차선을 늘리는 겁니다. 1차선(Single Channel) 대신 2차선(Dual Channel), 4차선(Quad Channel)으로 만들어 대역폭을 늘립니다.

④ 하버드 아키텍처 (Harvard Architecture)명령어(Instruction)와 데이터(Data)를 위한 버스를 완전히 분리합니다. 고속도로를 2개 만드는 셈이죠. 임베디드 시스템(ARM 등)에서 많이 씁니다.

하지만 결국 이거였다. 아무리 최적화해도 CPU와 메모리가 떨어져 있는 한, 버스는 영원한 병목이라는 사실을요.

"게이밍 PC 맞출 때 왜 메인보드를 비싼 거 사야 하나요?"

제가 2019년에 RTX 2080 Ti를 샀을 때 이 질문을 처음 받았습니다. 친구가 "그래픽카드만 비싸면 되지, 메인보드는 싸구려도 되지 않냐?"고 물었거든요.

답은 PCIe (PCI Express) 버스 때문입니다.

Peripheral Component Interconnect Express. 줄여서 PCIe.

CPU와 고속 주변장치(그래픽카드, NVMe SSD 등)를 연결하는 직렬 버스 규격입니다.

과거의 PCI 버스(병렬)는 모든 장치가 하나의 버스를 공유했습니다. 한 번에 한 장치만 데이터를 보낼 수 있었죠. 하지만 PCIe는 각 장치마다 전용 레인(Lane)을 할당합니다.

레인은 고속도로의 차선입니다.

| 버전 | 레인당 속도 (양방향 합계) | x16 레인 속도 |

|---|---|---|

| PCIe 1.0 | 250 MB/s | 4 GB/s |

| PCIe 2.0 | 500 MB/s | 8 GB/s |

| PCIe 3.0 | 985 MB/s (약 1 GB/s) | ~16 GB/s |

| PCIe 4.0 | 1969 MB/s (약 2 GB/s) | ~32 GB/s |

| PCIe 5.0 | 3938 MB/s (약 4 GB/s) | ~64 GB/s |

| PCIe 6.0 | 7877 MB/s (약 8 GB/s) | ~128 GB/s |

제가 친구 컴퓨터에서 직접 실험해봤습니다.

결과 (Cyberpunk 2077, 4K Ultra Ray Tracing):

왜 이런 일이 생길까요?

GPU가 계산은 다 끝냈는데, 텍스처(Texture)와 모델(Mesh) 데이터를 CPU에서 받아오는 속도가 느려서 대기합니다. 버스가 병목인 거죠.

특히 고해상도(4K, 8K) + 레이트레이싱 환경에서는 VRAM과 System RAM 간 데이터 교환이 빈번해서 PCIe 대역폭이 중요합니다.

재밌는 기능이 하나 더 있습니다. Bifurcation.

메인보드가 x16 슬롯을 x8 + x8 또는 x4 + x4 + x4 + x4로 쪼갤 수 있습니다.

예를 들어:

이렇게 2개의 GPU를 동시에 쓸 수 있습니다. 머신러닝 서버에서 많이 씁니다.

받아들였다. 메인보드가 비싼 이유가 PCIe 레인 개수와 버전 때문이라는 것을요. 싸구려 메인보드는 PCIe 3.0에 레인도 적습니다.

"왜 포트 모양이 다 다를까요?"

90년대생인 저는 초등학교 때 집에 있던 Windows 98 컴퓨터를 선명히 기억합니다. PC 뒷면을 보면 정말 온갖 포트가 난잡하게 박혀 있었습니다.

각 장치마다 전용 포트가 있었고, 꽂는 방향도 달랐습니다. 특히 프린터 케이블은 나사로 조여야 했죠.

어린 마음에 "왜 이렇게 복잡하게 만들었을까?" 싶었습니다.

그리고 1998년, USB (Universal Serial Bus)가 나왔습니다.

하지만 속도가 너무 느려서 처음엔 잘 안 퍼졌습니다.

이름이 너무 복잡해서 소비자들이 혼란스러워했습니다. 마케팅 팀이 뭘 한 건지...

바로 버스 통합(Bus Convergence) 덕분입니다.

과거에는:

이제는 USB-C 케이블 안에 여러 버스 신호를 다중화(Multiplexing)해서 보냅니다:

즉, USB-C는 단순한 USB 버스가 아니라 메인보드의 모든 버스를 밖으로 연장한 것입니다.

정리해본다. PS/2 키보드 쓰던 시절부터 USB4까지, 버스의 역사는 "통합과 고속화"의 역사였습니다.

여러 장치가 동시에 버스를 쓰고 싶어 하면 어떻게 될까요?

상상해보세요. CPU, DMA 컨트롤러, GPU, NVMe SSD가 모두 동시에 "나 버스 써야 돼!"라고 외칩니다.

버스는 물리적으로 한 번에 하나의 신호만 보낼 수 있습니다. (병렬 전송이라 해도 한 시점에는 한 마스터만)

그럼 누가 먼저 쓸까요? 싸움이 나겠죠.

이 문제를 해결하는 게 Bus Arbitration (버스 중재)입니다.

우선순위 예시:

시나리오: 당신이 4K 유튜브 영상을 보면서 동시에 100GB 파일을 다운로드합니다.

동시에 일어나는 일:

버스 중재자: "잠깐만! 차례차례!"

이해했다. 버스가 공유 자원이기 때문에 교통정리가 필요하다는 것을요.

2000년대 초반까지 인텔 CPU는 Front-side Bus (FSB)를 썼습니다.

CPU와 노스브리지 칩(Northbridge Chip) 사이를 연결하는 버스였습니다.

[CPU] <-- FSB --> [Northbridge] <--> [RAM]

↓

[Southbridge] <--> [HDD, USB, etc.]

문제는 FSB가 병목이었다는 겁니다.

CPU가 빨라도 FSB가 느려서 데이터를 못 받아옵니다. 또 폰 노이만 병목입니다.

인텔이 2008년, Core i7 (Nehalem)부터 FSB를 없애고 QPI를 도입했습니다.

핵심 변화:

[CPU Core 1] ┐

[CPU Core 2] ├─ Integrated Memory Controller ─> [RAM]

[CPU Core 3] ┘ ↓ QPI

[다른 CPU 또는 I/O Hub]

속도: 25.6 GB/s (FSB보다 약 10배 빠름)

인텔이 QPI를 개선한 버전.

예시: Xeon Platinum 8380 프로세서 2개를 UPI로 연결 → 80 코어 시스템 구성 가능.

AMD는 Ryzen 시리즈부터 Infinity Fabric이라는 자체 인터커넥트를 씁니다.

속도: DDR4-3200 메모리 사용 시, Infinity Fabric도 1600 MHz로 동기화 (2:1 비율)

와닿았다. Front-side Bus 시절의 병목을 해결하기 위해 아예 메모리 컨트롤러를 CPU 안에 넣어버린 것이었습니다.

1990년대 후반, 제가 Windows 98 쓸 때 경험한 일입니다.

CD 굽기 프로그램(Nero Burning ROM)으로 CD를 구울 때, 컴퓨터가 완전히 멈췄습니다. 마우스도 안 움직이고, 음악도 끊겼습니다.

왜 그랬을까요? PIO (Programmed I/O) 모드 때문이었습니다.

PIO: CPU가 일일이 데이터를 옮김.

# 의사 코드 - PIO 방식으로 하드디스크에서 RAM으로 1GB 파일 복사

file_size = 1_000_000_000 # 1GB

bytes_copied = 0

while bytes_copied < file_size:

byte = read_from_hdd() # CPU가 직접 HDD에서 1바이트 읽음

write_to_ram(byte) # CPU가 직접 RAM에 1바이트 씀

bytes_copied += 1

# CPU는 이 작업 외에 다른 걸 못 함!

결과: CPU 사용률 100%. 다른 프로그램 실행 불가.

"CPU야, 너는 비싸고 귀한 몸이니까 이런 허드렛일 하지 마. DMA 컨트롤러가 대신 할게."

DMA 방식:

# 의사 코드 - DMA 방식

def copy_file_with_dma(source, destination, size):

# CPU가 DMA 컨트롤러에게 명령만 내림

dma_controller.setup(

source_address=source,

dest_address=destination,

byte_count=size,

operation="COPY"

)

dma_controller.start()

# CPU는 이제 다른 일 할 수 있음

play_youtube_video()

browse_web()

# DMA가 끝나면 인터럽트로 알려줌

wait_for_interrupt("DMA_COMPLETE")

print("파일 복사 완료!")

핵심: CPU가 명령만 내리고, 실제 데이터 전송은 DMA 컨트롤러가 알아서 함.

현대 NVMe SSD는 DMA를 극도로 활용합니다.

NVMe SSD 읽기 과정:

성능 차이:

| 방식 | CPU 사용률 | 읽기 속도 |

|---|---|---|

| PIO | 100% | ~100 MB/s |

| DMA (SATA) | ~5% | ~550 MB/s |

| DMA (NVMe) | ~1% | ~7000 MB/s |

받아들였다. DMA 없이는 현대 컴퓨터가 불가능하다는 것을요. CPU가 모든 데이터 복사를 직접 했다면 멀티태스킹 자체가 불가능했을 겁니다.

이론만 알면 뭐 합니까. 직접 계산해봐야죠.

주어진 정보:

계산:

bus_width_bits = 64

clock_mhz = 1600 # 실제 클럭

ddr_multiplier = 2 # DDR이므로 2배

bus_width_bytes = bus_width_bits / 8 # 8 bytes

transfers_per_second = clock_mhz * 1_000_000 * ddr_multiplier

bandwidth_bytes_per_sec = bus_width_bytes * transfers_per_second

bandwidth_gb_per_sec = bandwidth_bytes_per_sec / (1024 ** 3)

print(f"대역폭: {bandwidth_bytes_per_sec:,.0f} bytes/s")

print(f"대역폭: {bandwidth_gb_per_sec:.2f} GB/s")

출력:

대역폭: 25,600,000,000 bytes/s

대역폭: 23.84 GB/s

주어진 정보:

계산:

bandwidth_per_lane_gb = 2 # GB/s

num_lanes = 16

total_bandwidth_gb = bandwidth_per_lane_gb * num_lanes

print(f"PCIe 4.0 x16 대역폭: {total_bandwidth_gb} GB/s")

출력:

PCIe 4.0 x16 대역폭: 32 GB/s

시나리오: 32비트 시스템에서 메모리 주소 0x12345678이 가리키는 물리적 위치는?

address_hex = "0x12345678"

address_dec = int(address_hex, 16)

print(f"16진수 주소: {address_hex}")

print(f"10진수 주소: {address_dec:,} bytes")

print(f"메가바이트: {address_dec / (1024**2):.2f} MB")

출력:

16진수 주소: 0x12345678

10진수 주소: 305,419,896 bytes

메가바이트: 291.27 MB

즉, 이 주소는 RAM의 약 291MB 위치를 가리킵니다.

친구 재민이의 "왜 8GB 램을 4GB밖에 못 써?"라는 질문에서 시작된 여정이 여기까지 왔습니다.

핵심 깨달음들을 정리해본다:

결국 이거였다.

컴퓨터의 모든 성능 문제는 "데이터를 얼마나 빨리 나를 수 있는가?"로 귀결됩니다. CPU가 아무리 빨라도 데이터가 안 오면 소용없고, GPU가 아무리 좋아도 PCIe가 느리면 병목입니다.

버스는 컴퓨터의 고속도로이자 혈관입니다.

재민이에게 이제 자신있게 말할 수 있습니다.

"야, 64비트로 다시 깔아. 주소 버스가 32비트면 2의 32승인 43억 개 주소밖에 못 만들거든. 43억 바이트가 4GB야. 네 램이 8GB여도 나머지는 주소 번호 자체가 없어서 못 쓰는 거야. 이제 알았지?"

Summer 2010. My college friend Jaemin called me, super excited.

"Dude! I finally got a desktop PC! Spent 3 hours at the PC cafe with the owner. He said I need lots of RAM for gaming, so I maxed out with 8GB!"

Back then, during the Core 2 Duo era, 8GB RAM was premium-tier. I was running 4GB and honestly jealous.

A week later, Jaemin called again. This time his voice was deflated.

"Bro... something's weird. I checked System Properties and it says 'Installed RAM: 8.00GB (3.25GB usable)'. Did the shop owner scam me?"

I had no clue either. After some Googling, I found the answer.

Me: "Jaemin, did you install Windows 7 32-bit?" Jaemin: "Huh? What's that? I just installed Windows 7..." Me: "You need to reinstall with 64-bit. 32-bit can only use 4GB of RAM." Jaemin: "What's 32-bit? Why does a smaller number limit my RAM? And why exactly 4GB? Why not 5GB?"

I didn't know the precise answer back then. Just "32-bit is old, so..." kind of understanding.

This mystery was finally solved 2 years later in my Computer Architecture class. When the professor wrote one line on the board, it hit me like a hammer.

"Address Bus Width = 32 bits → 2³² = 4,294,967,296 bytes = 4GB"Oh. The address is 32 bits. That's what it was all along.

The secret was in the Bus System.

When I first heard "Bus System," I was genuinely confused.

"CPU Bus", "System Bus", "Front-side Bus"... Are we talking about vehicles? Do tiny buses drive around inside the motherboard? My mind was literally imagining little buses transporting data.

I looked up Wikipedia: "A bus is a communication system that transfers data between components inside a computer." Still didn't click.

Then my professor gave an analogy that made everything clear.

"Think about how you get from home to campus. There's a road, and cars drive on it, right? Computers work the same way. For data (people) to travel from the CPU (home) to memory (campus), you need physical wires carrying electrical signals. That's the bus. Look closely at a motherboard—those golden traces etched everywhere? Those are bus lines."

Now I understood!

A bus isn't public transportation—it's the physical road (electrical circuit) that data travels on. And the road's width (bit width), speed (clock frequency), and number of lanes all determine computer performance.

Back to Jaemin's 8GB RAM problem.

When the professor wrote this on the board, the puzzle pieces finally fit together.

Address Bus = 32 bits

→ Possible addresses = 2^32 = 4,294,967,296

→ Each address points to 1 byte

→ Total: 4,294,967,296 bytes = 4GB

It clicked!

Every byte in memory has a unique address number. Like apartment unit numbers: "101", "102", "103"... In a 32-bit system, you can only create about 4.3 billion different numbers.

So what about memory beyond the 4 billionth address (beyond 4GB)? The CPU literally has no number to call it.

Even if you physically plug in 8GB of RAM, the CPU can't say "Hey 5GB location, give me that data" because that number doesn't exist in the addressing scheme.

It's like a mail carrier who can only write 4-digit zip codes trying to deliver to a 5-digit address. Physically impossible due to format limitations.

In contrast, 64-bit systems?

2^64 = 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 bytes

≈ 18 Exabytes

= 18,000,000 TB

Essentially infinite. We won't exhaust 64-bit address space in our lifetimes. (Even the world's biggest supercomputers use petabytes)

Now I could confidently explain to Jaemin:

"Dude, 32-bit OS can only write addresses as 32-digit binary numbers. That means 2^32 = 4.3 billion possible addresses. 4.3 billion bytes = 4GB. Even though you have 8GB physically installed, the remaining 4GB has no address numbers, so it can't be accessed. Reinstall with 64-bit."

So buses aren't just one thing. Looking at the CPU-Memory architecture diagram my professor drew, I saw three types of lines.

Role: Specifies "Where"

The mail delivery analogy works perfectly here.

The CPU is the mail carrier. Memory is a massive apartment complex (4.3 billion units). For the CPU to request "fetch data from Building 101, Unit 502," it needs to specify an address.

Characteristics:

Real calculation example:

# Calculate max memory based on address bus width

def max_memory(address_bits):

max_addresses = 2 ** address_bits

max_bytes = max_addresses # 1 address = 1 byte

max_GB = max_bytes / (1024 ** 3)

return max_GB

print(f"16-bit: {max_memory(16):.6f} GB") # 0.000061 GB = 64KB

print(f"32-bit: {max_memory(32):.6f} GB") # 4 GB

print(f"64-bit: {max_memory(64):.0f} GB") # 17,179,869,184 GB

Output:

16-bit: 0.000061 GB

32-bit: 4.000000 GB

64-bit: 17179869184 GB

Jaemin's 8GB RAM mystery: completely solved.

Role: Carries "What" (the actual data)

Once the address bus specifies where to go, we need to actually move the data. The data bus is the cargo truck.

At the same clock speed, 64-bit is theoretically 2x faster since it hauls 2x more data per round trip.

Characteristics:

Real bandwidth calculation:

# Bus bandwidth formula

# Bandwidth (MB/s) = (Bus Width in bits / 8) × Clock Speed (MHz) × Transfer Rate

def bus_bandwidth(bus_width_bits, clock_mhz, transfers_per_clock=1):

bus_width_bytes = bus_width_bits / 8

bandwidth_mb_per_sec = bus_width_bytes * clock_mhz * transfers_per_clock

return bandwidth_mb_per_sec

# Example 1: DDR4-3200 memory (64-bit bus, 3200MHz, DDR = 2 transfers)

ddr4_bandwidth = bus_bandwidth(64, 3200, 2)

print(f"DDR4-3200: {ddr4_bandwidth:,.0f} MB/s = {ddr4_bandwidth/1024:.1f} GB/s")

# Example 2: 32-bit system with 800MHz memory

old_bandwidth = bus_bandwidth(32, 800, 2)

print(f"32-bit 800MHz DDR: {old_bandwidth:,.0f} MB/s = {old_bandwidth/1024:.1f} GB/s")

Output:

DDR4-3200: 51,200 MB/s = 50.0 GB/s

32-bit 800MHz DDR: 6,400 MB/s = 6.2 GB/s

Now I understood why 64-bit systems are faster: not just the address space, but 2x more data per transfer.

Role: Commands "Actions"

Once we know where (address) and what (data), we need to specify "when" and "how."

The control bus sends signals like:

Characteristics:

Think of it as traffic lights: red (Wait), green (Go), left turn (Write), straight (Read).

Every computer we use follows Von Neumann Architecture.

Core concept: CPU and memory are physically separated and share a single bus.

Why is this a problem?

Imagine the CPU is a Ferrari F8. Top speed 340 km/h. But the road connecting CPU and memory is a one-lane highway in bumper-to-bumper traffic.

No matter how fast the Ferrari is, it can't speed if the car ahead is crawling. This is the Von Neumann Bottleneck.

The numbers are even more shocking.

| Component | Latency | CPU Clock Cycles |

|---|---|---|

| L1 Cache (inside CPU) | ~1 ns | ~4 cycles |

| L2 Cache | ~3 ns | ~12 cycles |

| L3 Cache | ~12 ns | ~40 cycles |

| DDR4 RAM | ~100 ns | ~300 cycles! |

| NVMe SSD | ~100,000 ns | ~300,000 cycles |

When the CPU fetches data from main memory (RAM), it waits about 300 clock cycles.

For a 3GHz CPU that can execute 3 billion instructions per second, waiting 300 cycles means 300 instructions could have executed in that time.

The Von Neumann Bottleneck in a nutshell:

"CPU (computation) advancement speed >> Memory (data supply) advancement speed"

Result: CPU finishes calculations but sits idle waiting for next data.

Hardware engineers have battled this for decades.

① Cache Memory (L1, L2, L3 Cache)Embed tiny memory inside the CPU. "Keep frequently used data nearby."

Transfer data on both the rising edge and falling edge of the clock signal. 2 transfers per clock cycle = 2x speed.

③ Multi-channel Memory (Dual/Quad Channel)Add more highway lanes. Instead of single-channel (1 lane), use dual-channel (2 lanes) or quad-channel (4 lanes) to increase bandwidth.

④ Harvard ArchitectureCompletely separate buses for instructions and data. Like building two highways. Common in embedded systems (ARM, etc.).

But here's the fundamental truth I accepted: As long as CPU and memory are physically separated, the bus will eternally be a bottleneck, no matter how much we optimize.

"Why do I need an expensive motherboard for a gaming PC?"

I first got this question in 2019 when I bought an RTX 2080 Ti. A friend asked, "Isn't the graphics card the only expensive part? Can't I cheap out on the motherboard?"

The answer: PCIe (PCI Express) bus.

Peripheral Component Interconnect Express. PCIe for short.

A serial bus standard connecting the CPU to high-speed peripherals (graphics cards, NVMe SSDs, etc.).

The old PCI bus (parallel) had all devices sharing one bus. Only one device could send data at a time. But PCIe allocates dedicated lanes to each device.

Lanes are highway lanes.

| Version | Per-Lane Speed (bidirectional) | x16 Lane Speed |

|---|---|---|

| PCIe 1.0 | 250 MB/s | 4 GB/s |

| PCIe 2.0 | 500 MB/s | 8 GB/s |

| PCIe 3.0 | 985 MB/s (~1 GB/s) | ~16 GB/s |

| PCIe 4.0 | 1969 MB/s (~2 GB/s) | ~32 GB/s |

| PCIe 5.0 | 3938 MB/s (~4 GB/s) | ~64 GB/s |

| PCIe 6.0 | 7877 MB/s (~8 GB/s) | ~128 GB/s |

I actually tested this on my friend's computer.

Results (Cyberpunk 2077, 4K Ultra Ray Tracing):

Why does this happen?

The GPU finishes calculations, but texture and mesh data transfer from CPU is slow, causing waits. The bus is the bottleneck.

Especially in high-resolution (4K, 8K) + ray tracing scenarios, frequent VRAM ↔ System RAM data exchange makes PCIe bandwidth critical.

There's one more interesting feature: Bifurcation.

Motherboards can split an x16 slot into x8 + x8 or x4 + x4 + x4 + x4.

Example:

This lets you run 2 GPUs simultaneously. Common in machine learning servers.

I finally accepted it. Expensive motherboards are worth it because of PCIe lane count and version. Cheap motherboards have PCIe 3.0 with fewer lanes.

"Why are there so many different port shapes?"

As a '90s kid, I vividly remember the Windows 98 computer at home in elementary school. The back of the PC had a chaotic array of ports:

Each device had its own dedicated port with different orientations. The printer cable even needed screws to secure it.

Young me wondered: "Why make it so complicated?"

Then in 1998, USB (Universal Serial Bus) arrived.

But it was too slow initially, so adoption was slow.

The naming was so confusing consumers were lost. What was the marketing team thinking...

Thanks to Bus Convergence.

In the past:

Now USB-C cables multiplex multiple bus signals:

USB-C isn't just a USB bus—it's all motherboard buses extended outside.

In summary: From the PS/2 keyboard era to USB4, bus history has been about "integration and speed".

What happens when multiple devices want to use the bus simultaneously?

Imagine: CPU, DMA controller, GPU, and NVMe SSD all shouting "I need the bus!"

The bus can physically only carry one signal at a time. (Even with parallel transmission, only one master at any moment)

So who goes first? Chaos would ensue.

Bus Arbitration solves this.

Priority example:

Scenario: You're watching a 4K YouTube video while downloading a 100GB file.

Simultaneous events:

Bus Arbiter: "Hold on! Take turns!"

I understood: Since the bus is a shared resource, traffic control is essential.

Until the early 2000s, Intel CPUs used the Front-side Bus (FSB).

The bus connecting CPU and Northbridge chip.

[CPU] <-- FSB --> [Northbridge] <--> [RAM]

↓

[Southbridge] <--> [HDD, USB, etc.]

Problem: FSB was a bottleneck.

Fast CPU but slow data delivery. Von Neumann Bottleneck again.

In 2008, Intel eliminated FSB with Core i7 (Nehalem), introducing QPI.

Key change:

[CPU Core 1] ┐

[CPU Core 2] ├─ Integrated Memory Controller ─> [RAM]

[CPU Core 3] ┘ ↓ QPI

[Other CPU or I/O Hub]

Speed: 25.6 GB/s (~10x faster than FSB)

Intel's improved QPI version.

Example: Connect two Xeon Platinum 8380 processors via UPI → 80-core system.

AMD uses Infinity Fabric starting with Ryzen.

Speed: With DDR4-3200 memory, Infinity Fabric syncs at 1600 MHz (2:1 ratio)

I realized: To solve the FSB bottleneck, they moved the memory controller inside the CPU entirely.

Late '90s, when I used Windows 98, I experienced this:

When burning a CD with Nero Burning ROM, the computer completely froze. Mouse wouldn't move, music stopped.

Why? PIO (Programmed I/O) mode.

PIO: CPU manually moves every byte.

# Pseudocode: Copying 1GB file from HDD to RAM using PIO

file_size = 1_000_000_000 # 1GB

bytes_copied = 0

while bytes_copied < file_size:

byte = read_from_hdd() # CPU directly reads 1 byte from HDD

write_to_ram(byte) # CPU directly writes 1 byte to RAM

bytes_copied += 1

# CPU can't do anything else during this!

Result: 100% CPU usage. Can't run other programs.

"CPU, you're too valuable for this grunt work. Let the DMA controller handle it."

DMA approach:

# Pseudocode: DMA method

def copy_file_with_dma(source, destination, size):

# CPU just issues command to DMA controller

dma_controller.setup(

source_address=source,

dest_address=destination,

byte_count=size,

operation="COPY"

)

dma_controller.start()

# CPU is now free to do other things

play_youtube_video()

browse_web()

# DMA notifies via interrupt when done

wait_for_interrupt("DMA_COMPLETE")

print("File copy complete!")

Key point: CPU just issues the command, DMA controller handles actual data transfer.

Modern NVMe SSDs heavily utilize DMA.

NVMe SSD read process:

Performance comparison:

| Method | CPU Usage | Read Speed |

|---|---|---|

| PIO | 100% | ~100 MB/s |

| DMA (SATA) | ~5% | ~550 MB/s |

| DMA (NVMe) | ~1% | ~7000 MB/s |

I accepted: Modern computing would be impossible without DMA. If CPU had to manually copy all data, multitasking itself would be impossible.