inode: Metadata of Unix Files

Filename is just a shell in Linux. The real identity is inode number. Secret of ls -i.

Filename is just a shell in Linux. The real identity is inode number. Secret of ls -i.

Why does my server crash? OS's desperate struggle to manage limited memory. War against Fragmentation.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

Fast by name. Partitioning around a Pivot. Why is it the standard library choice despite O(N²) worst case?

Establishing TCP connection is expensive. Reuse it for multiple requests.

I used to think filenames were everything. hello.txt was the file, right? Wrong. Linux doesn't care about hello.txt. It cares about inode number 12345678. The name is just a human-friendly alias. The real identity card is a number.

I stumbled into this while studying the error. No space left on device. I checked disk usage: 47%. Wait, what? How is the disk full when half the space is free? I googled "disk full but space available linux". Stack Overflow top answer: "Check your inodes. Run df -i."

Inodes? Never heard of them. I ran df -i:

$ df -i

Filesystem Inodes IUsed IFree IUse% Mounted on

/dev/sda1 1000000 1000000 0 100% /

100% inode usage. The disk had space, but inodes were exhausted. In environments where logs accumulate heavily, a logging library that creates millions of tiny 1KB files can exhaust all inodes. Each file needs an inode, and once they run out, No space left on device appears even with free disk blocks.

That night, I fell down the inode rabbit hole. Here's what I learned.

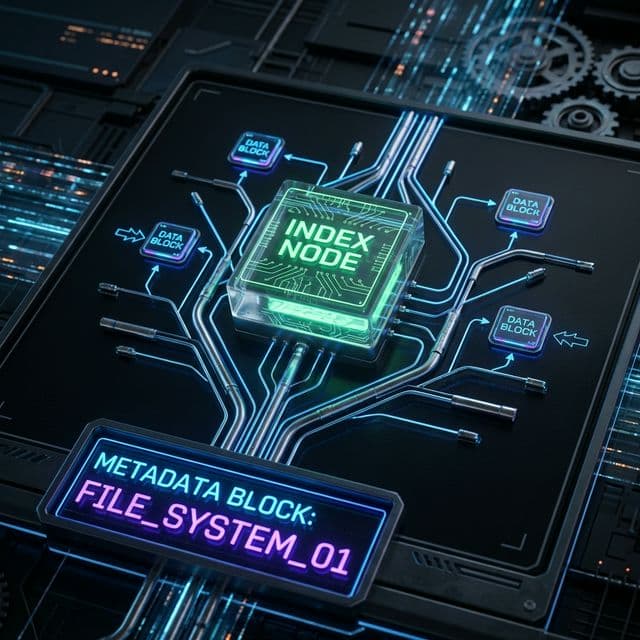

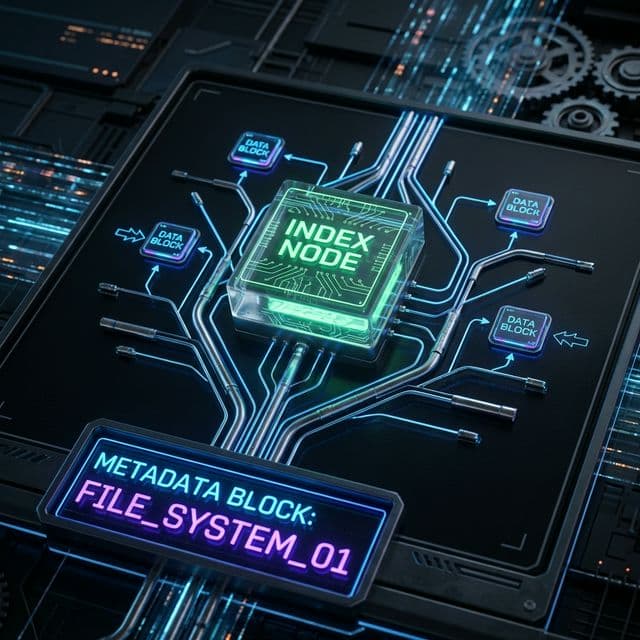

An inode (index node) is like a social security number for files. When you create a file, Linux assigns it an inode number. That number is the file's real identity. The filename is stored separately, in the directory.

Think of it this way:

Let's see it in action. Run ls -i:

$ ls -i

12345678 hello.txt

12345679 world.txt

12345680 README.md

Those numbers are inode numbers. To Linux, hello.txt is just file 12345678. The name is a convenience for humans. Under the hood, everything uses the inode number.

Run stat on a file to see its inode contents:

$ stat hello.txt

File: hello.txt

Size: 1024 Blocks: 8 IO Block: 4096 regular file

Device: 802h/2050d Inode: 12345678 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 1000/ user) Gid: ( 1000/ user)

Access: 2025-03-15 10:30:00.000000000 +0900

Modify: 2025-03-15 10:25:00.000000000 +0900

Change: 2025-03-15 10:25:00.000000000 +0900

An inode stores:

rw-r--r--)Filenames are stored in directories. A directory is just a file containing a table like this:

Filename Inode Number

hello.txt 12345678

world.txt 12345679

README.md 12345680

When you mv hello.txt goodbye.txt, only the directory table gets updated. The inode stays the same. The data blocks stay the same. Renaming is O(1) because nothing gets copied.

Now hard links make sense. When you create a hard link:

$ ln hello.txt alias.txt

$ ls -i

12345678 hello.txt

12345678 alias.txt

Same inode number. Both names point to the same file. No data gets copied. The inode's link count goes from 1 to 2. A hard link is literally another name in the directory table pointing to the same inode.

Delete hello.txt:

$ rm hello.txt

$ ls -i

12345678 alias.txt

The file still exists. The data blocks are still there. Why? Because the inode's link count is 1, not 0. Only when the link count hits 0 does Linux delete the actual data.

This blew my mind. "Deleting a file" doesn't delete data. It removes a directory entry and decrements the link count. If other links exist, the data survives.

The inode stores pointers to data blocks. But files vary in size. Small files need a few pointers. Large files need thousands. How does ext4 handle this?

Three-tier pointer system:Analogy:

Most files are small, so direct pointers suffice. Large files pay the cost of traversing indirect blocks. It's a trade-off optimized for the common case.

Back to the inode exhaustion scenario. A server with 1 million inodes, a logging library creating 1 million tiny files. Disk blocks: 47% used. Inodes: 100% used.

When you run out of inodes, you get No space left on device even with free disk space. It's confusing because df -h shows plenty of room:

$ df -h

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/sda1 100G 47G 53G 47% /

But df -i reveals the truth:

$ df -i

Filesystem Inodes IUsed IFree IUse% Mounted on

/dev/sda1 1000000 1000000 0 100% /

The fix: delete files. Each deleted file frees an inode. We nuked the log directory:

$ find /var/log/app -type f -name "*.log" -delete

$ df -i

Filesystem Inodes IUsed IFree IUse% Mounted on

/dev/sda1 1000000 300000 700000 30% /

Crisis averted. Lesson learned: monitor both disk space AND inodes. Always check df -i, not just df -h.

You can't add more inodes after creating the filesystem. The count is set when you run mkfs.ext4. The default is roughly one inode per 16KB of disk space.

If you know you'll store millions of tiny files, increase the inode ratio:

$ mkfs.ext4 -i 8192 /dev/sda1

This creates one inode per 8KB instead of 16KB. More inodes, less space per inode. Trade-offs.

For most use cases, the default is fine. But if you're running a mail server (millions of small emails) or a cache directory (tons of temp files), bump the inode count.

Windows NTFS uses MFT (Master File Table) instead of inodes. Conceptually similar. Each file has an MFT entry storing metadata and data block pointers.

Key difference:

NTFS doesn't suffer from inode exhaustion because the MFT expands. But MFT fragmentation can hurt performance. Linux inodes are predictable and simple. You know upfront how many files you can create.

Hard links for deduplication: If you have identical config files across many directories, hard links instead of copies means the same inode with multiple names. Saves space and guarantees consistency.

Debugging "disk full" on build servers: CI/CD pipelines create tons of temp files. Monitoring df -i is worth making standard practice.

Understanding why mv is fast: Moving files within the same filesystem just updates the directory entry. The inode and data blocks don't move. Instant. Moving across filesystems requires copying data. Slow.

Zombie files: Deleted a large file, but df -h showed no space freed. Why? Another process had the file open. The directory entry was gone, but the inode persisted (link count 0, but open file descriptor keeps it alive). Kill the process, space freed.

Not all inodes are created equal.

This is why XFS is often recommended for massive storage servers, while Ext4 is the standard for boot drives.

A classic junior admin panic. You rm a 50GB log file, but df -h shows no change.

rm removes the directory entry and decrements the inode's Link Count. But since the process holds a file descriptor, the Reference Count > 0. The OS cannot free the inode or data blocks until the process releases it.systemctl restart apache2) or kill it.echo "" > access.log. This truncates the content to 0 bytes while keeping the inode alive.Symbolic Links (Soft Links) created with ln -s are different from Hard Links. They have their own inode.

So where is the "target path" stored?

How can Linux mount ext4, xfs, and ntfs drives all at once and treat them the same?

It's thanks to the VFS (Virtual File System) layer in the kernel.

When you run cp a.txt b.txt, the cp program doesn't know (or care) about the underlying filesystem. It just calls VFS system calls like open(), read(), write().

VFS translates these calls: "Oh, this file is on ext4, call the ext4_read function." or "This is on NFS, send a network packet."

This abstraction is the magic behind the Unix philosophy "Everything is a file".

Before learning about inodes, I thought hello.txt was the file. Now I know better. The filename is just a directory entry. The inode is the file's soul.

Try these commands:

ls -i to see inode numbersstat filename to inspect inode metadatadf -i to check inode usageln file1 file2 to create hard links and observe shared inodesFilesystems are invisible infrastructure. Inodes are at the heart of that design. Once you see the numbers behind the names, Linux file management makes a lot more sense.

Q: Can I increase inodes without formatting?

A: On Ext4, NO. You must format (mkfs). That's why planning ahead with df -i is critical. XFS handles this better dynamically.

Q: Do directories use inodes? A: Yes. A directory is just a file containing a list of names. It consumes one inode.

Q: do Hard Links use new inodes? A: No. They point to the existing inode. They just increase the Reference Count.