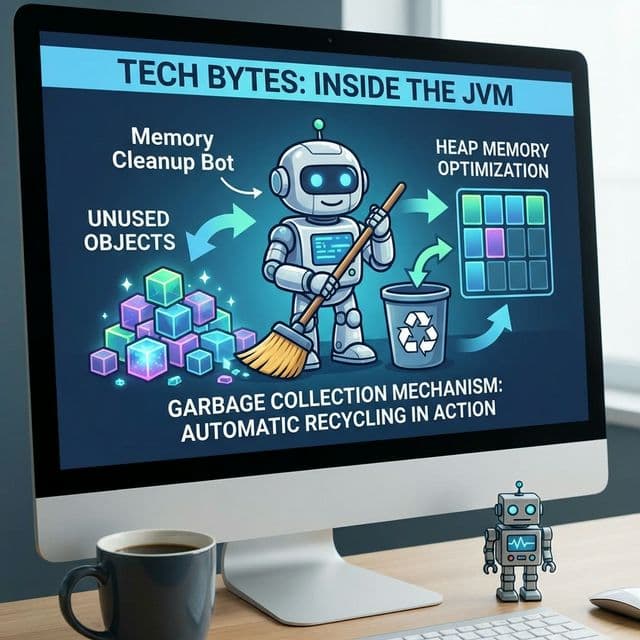

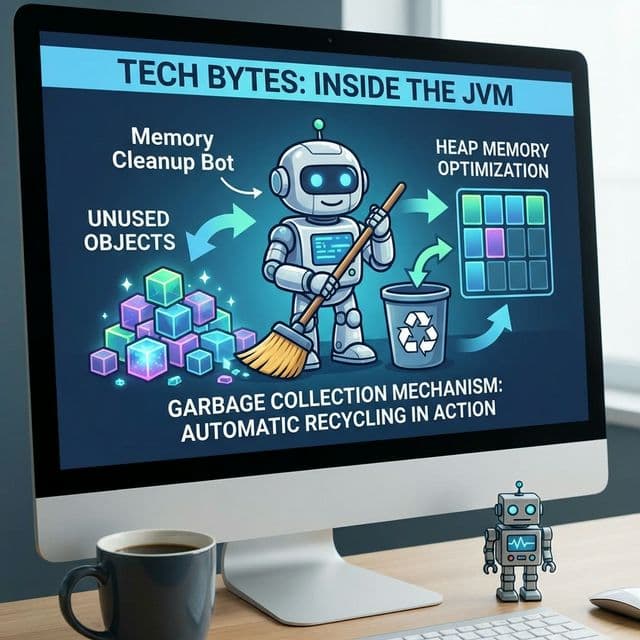

Garbage Collection (GC)

Janitor cleaning up developer's mess. Convenient, but sometimes blocks the hallway (Stop The World).

Janitor cleaning up developer's mess. Convenient, but sometimes blocks the hallway (Stop The World).

Why does my server crash? OS's desperate struggle to manage limited memory. War against Fragmentation.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

Fast by name. Partitioning around a Pivot. Why is it the standard library choice despite O(N²) worst case?

Establishing TCP connection is expensive. Reuse it for multiple requests.

I once tried building something like a game engine in C++. The task seemed simple: dynamically create objects with new, then destroy them with delete when done. The problem? Figuring out "when done" was way harder than I expected.

Some objects were referenced from multiple places, others lingered in ambiguous states. After 30 minutes of runtime, memory usage would balloon past 2GB and the system would crawl. I had a memory leak. Objects I forgot to delete piled up like zombies in memory.

That's when I asked myself: "Why do I have to manage memory manually? Should programmers really be responsible for taking out the trash?" The answer to that question was Garbage Collection (GC).

In C and C++, you manage memory by hand. You borrow with malloc or new, and return it with free or delete. Let me break down why this is hell.

// C-style memory management

void process_data() {

int* data = (int*)malloc(1000 * sizeof(int));

if (data == NULL) {

return; // allocation failed

}

// process data...

// Forget this? Memory leak!

free(data);

}

// More complex example

char* create_string() {

char* str = (char*)malloc(100);

strcpy(str, "Hello");

return str; // Who's responsible for freeing this?

}

void use_string() {

char* msg = create_string();

printf("%s\n", msg);

// Should call free(msg) here... but what if you forget?

}

First problem: Memory leaks. Forget to free, memory accumulates. Second problem: Double free or dangling pointers. Free already-freed memory or access it? Program crashes.

Third problem: Ownership confusion. When multiple functions point to the same memory, who's responsible for freeing it? These problems kept me up at night.

The first automation attempt was reference counting. Each object gets a counter: "How many references point to me?" Reference created? +1. Reference dropped? -1. Counter hits zero? Auto-deallocate.

// C++ reference counting (smart pointers)

#include <memory>

void reference_counting_example() {

std::shared_ptr<int> ptr1 = std::make_shared<int>(42);

// ref count: 1

{

std::shared_ptr<int> ptr2 = ptr1;

// ref count: 2

std::cout << *ptr2 << std::endl;

} // ptr2 out of scope, count: 1

std::cout << *ptr1 << std::endl;

} // ptr1 out of scope, count: 0 -> auto freed

I thought this was genius at first. But I soon discovered a fatal flaw: circular references.

// Circular reference in JavaScript

class Node {

constructor(value) {

this.value = value;

this.next = null;

}

}

let node1 = new Node(1);

let node2 = new Node(2);

node1.next = node2;

node2.next = node1; // circular reference!

// node1 references node2, node2 references node1

// neither can reach ref count 0

// never freed

If A references B and B references A, neither reaches zero. They're unreachable from outside but never freed. That's the limit of reference counting.

The real solution required a mindset shift. Not "how many references" but "reachable from root?" That's the core insight of modern GC.

Think of it like this: imagine cleaning an apartment complex. Reference counting asks "how many people touched this trash?" But GC asks "can I reach this by walking from the entrance?" Starting from the entrance (root), you walk through hallways, elevators, apartments. Objects you can reach are "in use," objects you can't are "garbage."

This is the Mark and Sweep algorithm.

Mark and Sweep has two phases.

Phase 1: Mark// Simplified Mark and Sweep concept

class GarbageCollector {

constructor() {

this.heap = [];

this.roots = [];

}

mark() {

const marked = new Set();

const stack = [...this.roots];

while (stack.length > 0) {

const obj = stack.pop();

if (marked.has(obj)) continue;

marked.add(obj);

// Add objects referenced by this object to stack

for (let ref of obj.references) {

stack.push(ref);

}

}

return marked;

}

sweep(marked) {

this.heap = this.heap.filter(obj => {

if (marked.has(obj)) {

return true; // keep

} else {

obj.free(); // release

return false;

}

});

}

collect() {

const marked = this.mark();

this.sweep(marked);

}

}

This approach perfectly solves circular references. Even if A and B reference each other, if unreachable from roots, both are garbage.

Mark and Sweep is elegant but scanning the entire heap every time is inefficient. That's where Generational GC comes in.

It's based on the observation: "Most objects die young." Newly created objects are likely to become garbage soon. Objects that survive tend to stick around.

So the heap is divided into generations.

Young Generation// V8's generational GC (conceptual)

// Young Generation has two spaces

// 1. From Space (living objects)

// 2. To Space (empty)

// Minor GC (Scavenger algorithm):

function minorGC() {

// Copy living objects from From Space to To Space

for (let obj of fromSpace) {

if (isReachable(obj)) {

copyTo(toSpace, obj);

obj.age++;

if (obj.age > PROMOTION_THRESHOLD) {

promoteToOldGen(obj); // promote to Old Gen

}

}

}

// Swap From and To

swap(fromSpace, toSpace);

clear(toSpace); // clear old From Space

}

// Major GC (Mark-Compact algorithm):

function majorGC() {

// Mark and Sweep across entire Old Generation

mark(roots);

compact(); // compact to reduce fragmentation

}

V8 (Chrome, Node.js) uses the Scavenger algorithm for Young Gen, copying living objects to new space. For Old Gen, it uses Mark-Compact, marking then compacting living objects to reduce fragmentation.

Thanks to this approach, most GCs only process the small Young Gen, making them fast. I understood this as the principle of "frequently used items on desk, rarely used in storage."

No matter how clever GC is, it must pause the program during cleanup. This is the Stop-The-World (STW) phenomenon.

Why pause? If new objects are created or references change during cleanup, GC might make wrong decisions. Like trying to clean while people keep moving stuff around.

The problem: users feel this pause. Ever experienced frame drops in games or stutter in web apps? Likely GC.

// Performance issue from GC

function processLargeData() {

const start = Date.now();

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

// Create new object every iteration (Young Gen pressure)

const temp = {

index: i,

data: new Array(100).fill(i)

};

// This object becomes garbage after loop iteration

}

const end = Date.now();

console.log(`Time: ${end - start}ms`);

// Multiple Minor GCs accumulate STW time

}

That led to improvements: Concurrent GC and Incremental GC.

Concurrent GC: Run application threads and GC threads simultaneously. Clean in the background without fully stopping. But implementation is complex, and some phases still need STW.

Incremental GC: Split GC work into small chunks, executing gradually. Instead of one long pause, many short pauses distributed over time. Modern V8 uses this approach.

"If there's GC, aren't memory leaks impossible?" I thought so too. But GC never collects "reachable" objects. The problem: objects accidentally left reachable.

// Memory leak example

function setupUserSession(userData) {

// setInterval captures userData in closure

const intervalId = setInterval(() => {

console.log(`User ${userData.name} is active`);

}, 1000);

// Problem: intervalId not stored anywhere

// No way to call clearInterval

// userData stays in memory forever

}

// Correct approach

function setupUserSession(userData) {

const intervalId = setInterval(() => {

console.log(`User ${userData.name} is active`);

}, 1000);

// Return cleanup function

return () => clearInterval(intervalId);

}

const cleanup = setupUserSession({ name: 'John', data: bigData });

// Later...

cleanup(); // memory freed

I caused a production memory leak with this pattern. Even after users left pages, setInterval kept running, holding large objects.

// Memory leak example

function createHeavyProcessor() {

const hugeArray = new Array(1000000).fill('data');

// This function doesn't actually use hugeArray

// But closure nature captures entire scope

return function processLight() {

console.log('Processing...');

// hugeArray unused but stays in memory

};

}

const processor = createHeavyProcessor();

// hugeArray stays in memory forever

// Correct approach

function createHeavyProcessor() {

const hugeArray = new Array(1000000).fill('data');

// Extract only needed data

const summary = hugeArray.length;

return function processLight() {

console.log(`Processing ${summary} items...`);

// hugeArray now eligible for GC

};

}

Closures are convenient but can unintentionally hold large objects. After experiencing this, I developed the habit of explicitly extracting only variables actually used in closures.

// Memory leak example

let detachedNodes = [];

function createAndRemoveElement() {

const div = document.createElement('div');

div.innerHTML = '<p>' + new Array(10000).join('text') + '</p>';

document.body.appendChild(div);

// Removed from DOM but JavaScript variable still references it

document.body.removeChild(div);

detachedNodes.push(div); // memory leak!

}

// Correct approach

function createAndRemoveElement() {

const div = document.createElement('div');

div.innerHTML = '<p>content</p>';

document.body.appendChild(div);

document.body.removeChild(div);

// Don't hold reference - GC can collect

}

Storing DOM nodes in JavaScript variables keeps them in memory even after browser removes them from DOM tree. This pattern is especially common in SPAs.

ES2021 added WeakRef and FinalizationRegistry. These "give hints to GC."

// WeakRef usage example

class ImageCache {

constructor() {

this.cache = new Map();

}

add(key, image) {

// Store wrapped in WeakRef

this.cache.set(key, new WeakRef(image));

}

get(key) {

const ref = this.cache.get(key);

if (!ref) return null;

// Access actual object with deref()

const image = ref.deref();

if (!image) {

// GC already collected it

this.cache.delete(key);

return null;

}

return image;

}

}

// Usage

const cache = new ImageCache();

let image = new Image();

image.src = 'large-image.png';

cache.add('hero', image);

// When done with image

image = null;

// GC can collect image under memory pressure

// But might keep it cached if memory is sufficient

FinalizationRegistry lets you run callbacks when objects are GC'd.

// FinalizationRegistry example

const registry = new FinalizationRegistry((heldValue) => {

console.log(`Object ${heldValue} was GC'd`);

});

function createUser(name) {

const user = { name };

// Execute callback when user object is GC'd

registry.register(user, name);

return user;

}

let user = createUser('Alice');

// use user...

user = null;

// Later when GC runs: "Object Alice was GC'd"

I initially understood these as "memory leak debugging tools," but later realized they're useful for cache implementations.

Production environments sometimes require GC tuning. Node.js controls GC via V8 flags.

# Adjust heap size

node --max-old-space-size=4096 app.js # Set Old Gen to 4GB

# Enable GC logging

node --trace-gc app.js

# Sample output:

# [12345:0x123456] 123 ms: Scavenge 2.3 (3.1) -> 1.9 (3.1) MB, 0.5 / 0.0 ms

# [12345:0x123456] 456 ms: Mark-sweep 15.2 (20.1) -> 12.3 (18.5) MB, 12.3 / 0.0 ms

Logs show GC type (Scavenge, Mark-sweep), heap size changes, and duration. I learned to use this information to determine "when GC runs too frequently" or "if heap size is insufficient."

// Monitor memory usage

function logMemoryUsage() {

const usage = process.memoryUsage();

console.log({

rss: `${Math.round(usage.rss / 1024 / 1024)}MB`, // total memory

heapTotal: `${Math.round(usage.heapTotal / 1024 / 1024)}MB`, // total heap

heapUsed: `${Math.round(usage.heapUsed / 1024 / 1024)}MB`, // heap used

external: `${Math.round(usage.external / 1024 / 1024)}MB` // C++ object memory

});

}

setInterval(logMemoryUsage, 5000);

If a server's memory keeps growing, that's a sign of memory leaks. Stable servers show heap usage in a consistent range with a sawtooth pattern (GC drops it, then it grows again).

Garbage collection is ultimately a "convenience vs performance tradeoff." Manual management in C/C++ is painful but gives perfect control. GC is convenient but carries costs like STW.

I only understood "why game engines use C++" and "why server developers obsess over GC tuning" after understanding GC. GC isn't magic, it's a sophisticated algorithm. Understanding how it works helps avoid memory leaks and optimize performance.

The most important lesson: "Having GC doesn't mean you can ignore memory management." Cleaning up timers, cutting unnecessary references, being careful with DOM nodes—these habits build stable applications. I now understand it this way: "GC is the janitor, but not making garbage is my responsibility."