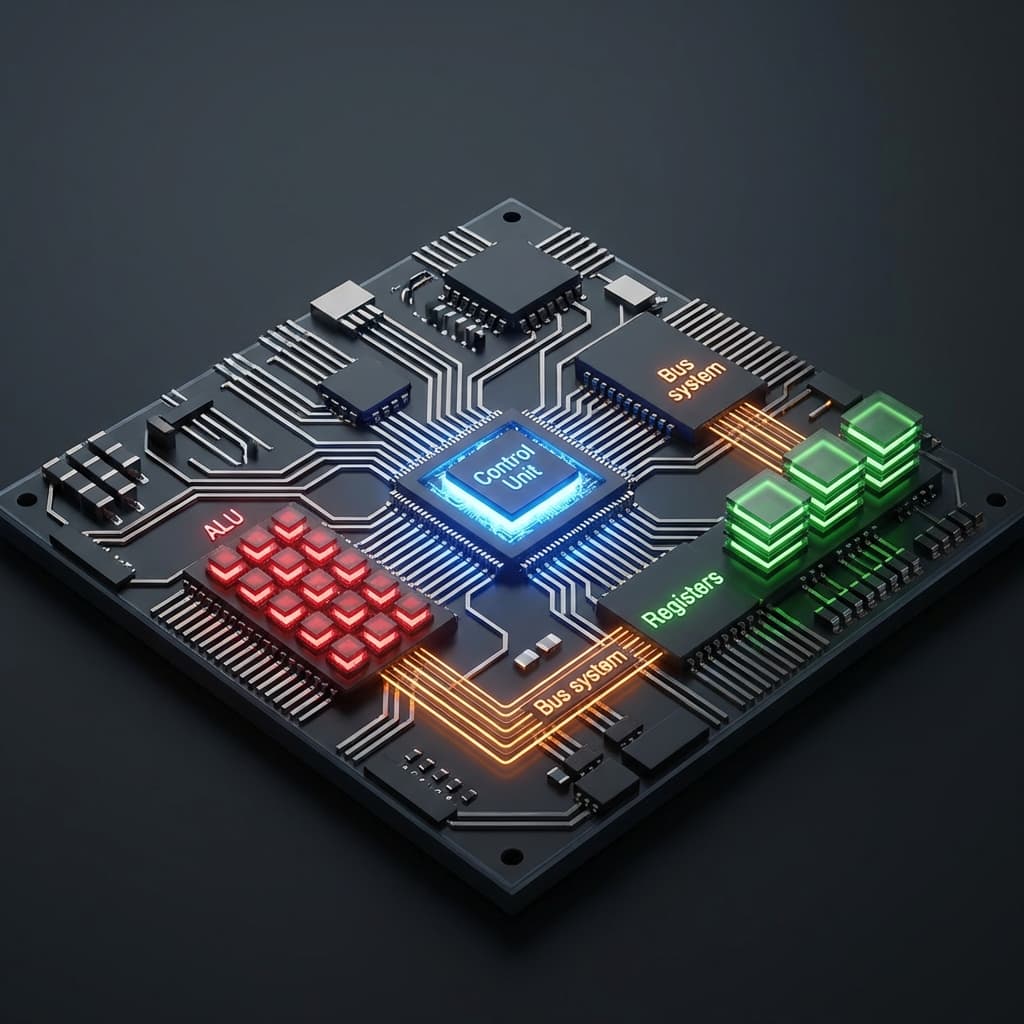

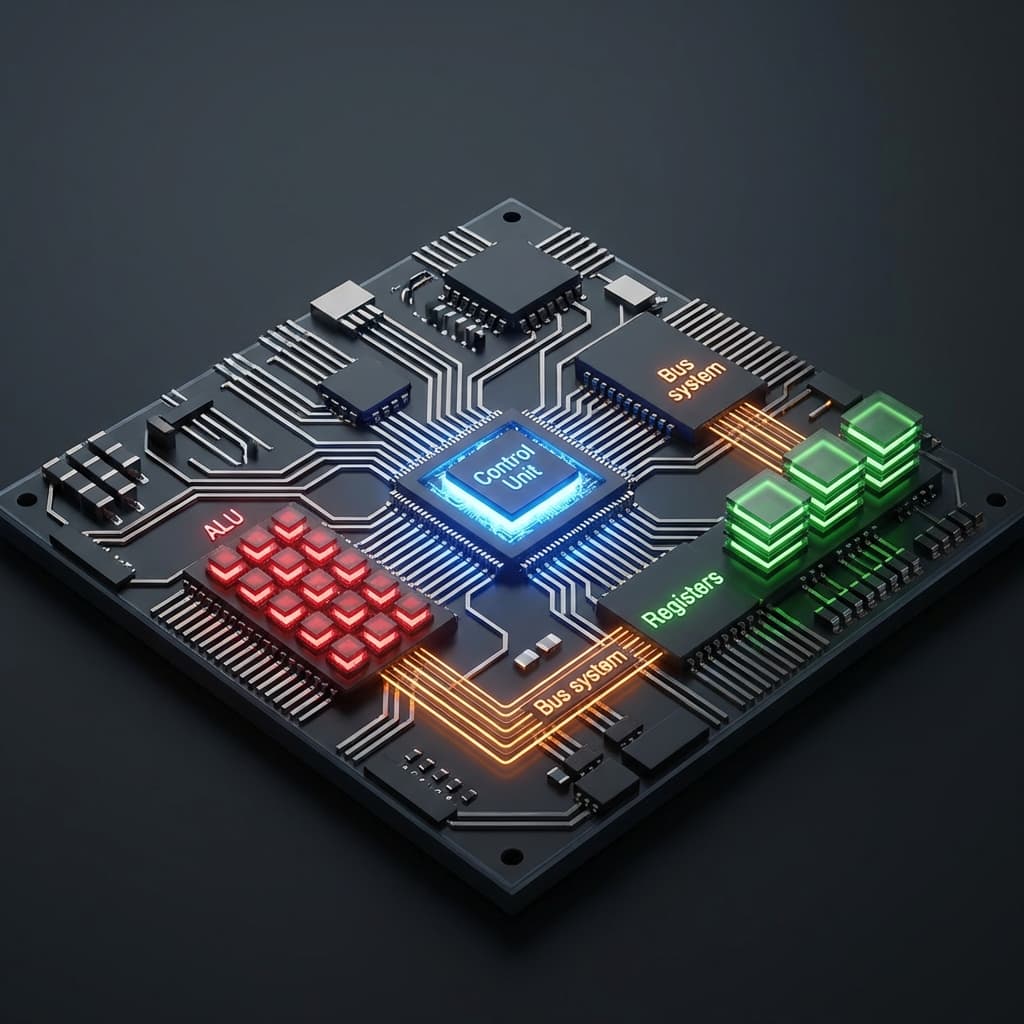

CPU Structure: CU, ALU, Registers

A CPU is actually a giant factory. Inside, there are Managers, Workers, and Workbenches.

A CPU is actually a giant factory. Inside, there are Managers, Workers, and Workbenches.

Why does my server crash? OS's desperate struggle to manage limited memory. War against Fragmentation.

Two ways to escape a maze. Spread out wide (BFS) or dig deep (DFS)? Who finds the shortest path?

Fast by name. Partitioning around a Pivot. Why is it the standard library choice despite O(N²) worst case?

Establishing TCP connection is expensive. Reuse it for multiple requests.

When you write code, sometimes you wonder, "Why is this so slow?" The profiler points to a specific function, but the algorithm complexity looks fine. Then terms like "cache miss" and "branch prediction failure" start appearing, and you realize: to truly understand performance, you need to know what happens inside the CPU.

So I decided to take the CPU apart — conceptually, not physically.

I thought the CPU was just "a fast calculator." Plug in electricity, get addition. Simple.

But looking at the actual structure, it's more intricate than expected:

Trying to understand everything at once was overwhelming, so I settled on a metaphor: the CPU is a factory.

Zoom into a CPU under a microscope, and you'll find a vast city inside. The easiest way to grasp it is by thinking of a factory with three key members:

These three are essentially the entire CPU. Everything else is a variation or optimization of this structure.

Think of an orchestra conductor. The CU fetches instructions from memory, decodes them, and issues orders to each component.

It doesn't do the heavy lifting, but it controls the entire flow. The Manager.

More specifically, the Control Unit:

0x1A into "Ah, this means ADD."Without the CU, even the fastest ALU wouldn't know what to calculate. It's a factory full of workers with no one telling them what to build.

This is where the actual computation happens. The ALU handles two kinds of operations:

Arithmetic Operations:

Logic Operations:

The ALU itself is simple. "Addition complete, boss." "Comparison done." It silently computes whatever it's told. The Worker.

But modern ALUs aren't just simple adders. They contain a dedicated FPU (Floating Point Unit) for decimal math, and SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) units that process multiple data points with a single instruction — a huge boost for image processing and scientific computation.

Ultra-fast temporary memory for the CPU. If RAM is a 'bookshelf', registers are the 'desk'.

Walking to the bookshelf every time wastes time. So we put the numbers we need right now on the desk (registers) to work fast.

General Purpose Registers: Temporary boxes for data being calculated. On x86: EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX. On ARM: R0–R15.

Special Purpose Registers:

| Memory Type | Access Time | Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Register | ~0.3ns | Sticky note on your desk |

| L1 Cache | ~1ns | Inside your desk drawer |

| L2 Cache | ~3–10ns | Bookshelf in the same room |

| RAM | ~50–100ns | Library at the end of the hallway |

| SSD | ~100,000ns | Warehouse in another building |

Registers are over 200x faster than RAM. If the CPU had to travel to RAM for every operation, performance would collapse. That's why the CPU loads only the data it needs immediately into registers, computes, then writes results back to memory.

From the moment a CPU powers on until it shuts down, it repeats one loop: the FDE (Fetch-Decode-Execute) cycle, billions of times per second.

These three steps process one instruction. Even a simple line like a = b + c; requires multiple FDE cycles: load b into a register, load c, add them, store the result at a's memory address.

The clock determines the speed of this cycle. It's like a metronome sending "tick, tick, tick" signals at regular intervals.

Each tick advances one stage of the FDE cycle (in practice, pipelining makes this more complex, but the principle holds). When we say a CPU is "fast," we mean this factory runs billions of cycles per second.

When designing a CPU, there's a fundamental philosophical divide: "Should instructions be complex or simple?"

Philosophy: "One instruction should do a lot."

Philosophy: "Keep instructions as simple as possible."

Here's the interesting thing: this distinction is blurring. Intel's x86 CPUs accept CISC instructions on the surface but internally translate them into RISC-style micro-ops for execution. Apple's M1/M2 chips are RISC-based (ARM) but deliver desktop-class performance with exceptional power efficiency.

It's not about "which is better" — it's a trade-off based on use case:

As you can see, the CPU isn't a creative brain. It's a mechanical factory where the Manager (CU) orders the Worker (ALU) to crunch data on the Desk (Registers).

But because this factory runs billions of times per second (GHz), it looks like genius to us.

Every time you type if, for, or +, this factory goes into emergency mode. The Manager yells, the Worker sweats, the Workbench reshuffles.

Understanding CPU structure makes a few things click:

If your code is slow, ask yourself: Am I running this factory inefficiently? (e.g., unnecessary memory accesses, branch-heavy logic, poor data locality)