Does Parent Render Always Trigger Child Render? A Deep Dive into React Optimization

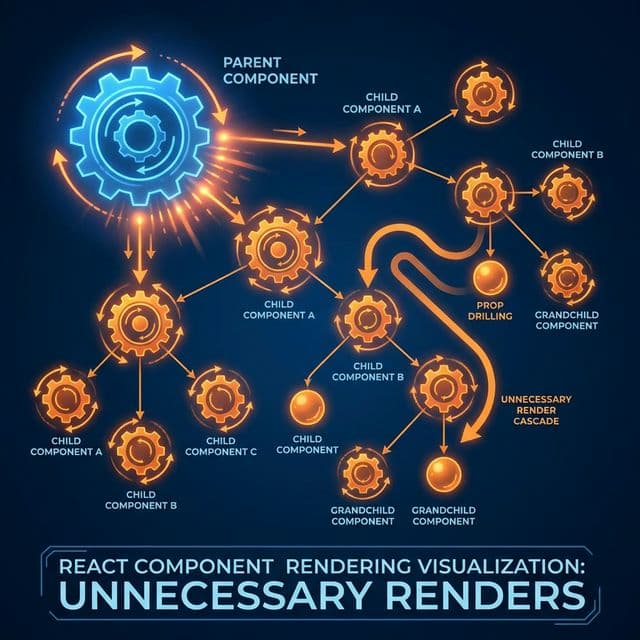

1. The Default Behavior: "Render Everything!"

A common misconception among React beginners is:

"If I don't change the props passed to a child component, it won't re-render, right?"

Wrong.

React's default rule is simple and slightly brutal:

"When a Parent Component renders (runs), all of its Child Components re-render recursively."

It doesn't matter if the props are identical to the last render. The default behavior is to re-execute the child function.

function Parent() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setCount(c => c + 1)}>Count: {count}</button>

<HeavyComponent />

</div>

);

}

Every time you click the button, Parent re-runs. Consequently, <HeavyComponent /> re-runs too, even though it takes no props at all. This is the "Cascading Render".

2. Why Does React Do This?

Is React inefficient? No, it's prioritizing Safety and Simplicity.

- Safety: Updates might happen via Context or other side channels (like direct DOM manipulation or global stores). Assuming "Props didn't change = No updates needed" could lead to Stale UI bugs where the screen shows old data.

- Performance Check: "Rendering" in React just means calling the function and creating a tree of objects (Virtual DOM). This is extremely fast in JavaScript via the V8 engine. The real heavy lifting is updating the actual Browser DOM, which React only does if the diffing result shows a change.

However, if <HeavyComponent /> works hard (e.g., calculates prime numbers, draws a complex SVG chart, or renders a list of 1000 items), re-running it on every keystroke in the Parent is a performance killer.

3. The Shield: React.memo

To opt-out of this default behavior, we use React.memo. It wraps a component and tells React: "Only re-render this component if its PROPS have actually changed."

const HeavyComponent = React.memo(function HeavyComponent() {

console.log("Heavy Rendered");

return <div className="chart">...</div>;

});

Now, if Parent updates its state, HeavyComponent will measure its previous props against its new props. If they are equal (shallow comparison), it skips the rendering phase entirely.

4. The Pitfall: Referential Equality

You wrapped your component in React.memo, but it's still re-rendering. Why?

Usually, it's because you are passing an Object or a Function as a prop.

In JavaScript:

"hello" === "hello" (True - Primitive)1 === 1 (True - Primitive){ id: 1 } === { id: 1 } (False! - Reference)() => {} === () => {} (False! - Reference)

Every time the Parent renders, it creates a new function instance or a new object literal. The memory address changes.

React.memo looks at the props, sees a new memory address for the onClick function, says "Props changed!", and triggers a re-render. This is the most common bug in React performance optimization.

The Solution: useMemo and useCallback

This is why hooks exist. They preserve the memory reference (pointer) across renders.

- useCallback: Caches a function definition.

- useMemo: Caches a value (object, array, or calculation result).

const handleClick = useCallback(() => {

console.log('hi');

}, []); // No dependencies -> Same function instance forever

const style = useMemo(() => ({ color: 'red' }), []);

return <Child onClick={handleClick} style={style} />; // Optimization Works!

5. The Elegant Pattern: Component Composition

Before you sprinkle memo and useCallback everywhere, there is a better way.

Change the Structure of your code.

Lift the expensive component UP, and pass it down as children.

Before (Slow)

function App() {

const [color, setColor] = useState('red');

return (

<div style={{ color }}>

<input onChange={e => setColor(e.target.value)} />

<ExpensiveChild /> {/* Re-renders when color changes */}

</div>

);

}

After (Fast)

function ColorPickerWrapper({ children }) {

const [color, setColor] = useState('red');

return (

<div style={{ color }}>

<input onChange={e => setColor(e.target.value)} />

{children} {/* This is just a prop! */}

</div>

);

}

function App() {

return (

<ColorPickerWrapper>

<ExpensiveChild /> {/* Created in App, not ColorPickerWrapper */}

</ColorPickerWrapper>

);

}

In the "After" example:

- When

ColorPickerWrapper updates its state (color), it re-renders.

- However, the

children prop it received from App is already created by App.

- Since

App didn't re-render, the reference to <ExpensiveChild /> hasn't changed.

- React sees the same exact element object and skips rendering

ExpensiveChild.

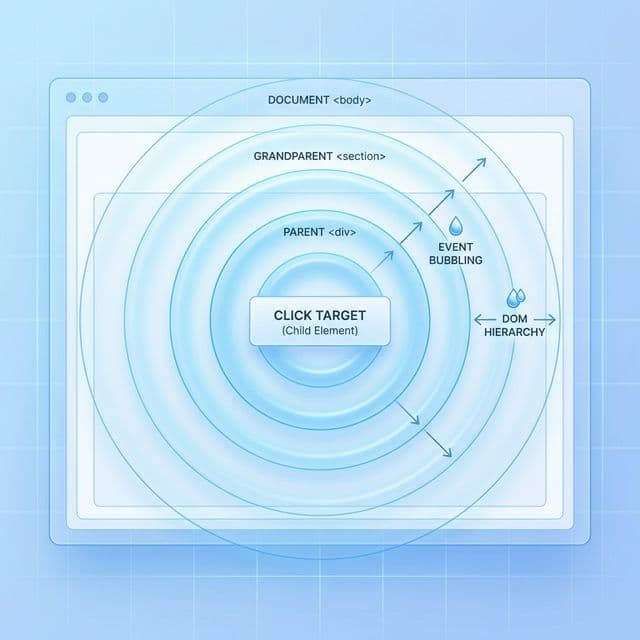

6. Context API Optimization

Another silent performance killer is the Context API.

When a Context Provider's value changes, ALL consumers of that context re-render, regardless of what part of the value they use.

The Problem

// Passing state and dispatch together. A BAD practice.

<MyContext.Provider value={{ state, dispatch }}>

<DisplayComponent /> {/* Uses state */}

<ButtonComponent /> {/* Uses dispatch */}

</MyContext.Provider>

When state updates, the value object is recreated. ButtonComponent re-renders even though dispatch hasn't changed. This causes unnecessary ripples of rerenders across your app.

The Fix: Split Contexts

Separate the contexts based on change frequency and responsibility.

<DispatchContext.Provider value={dispatch}>

<StateContext.Provider value={state}>

<DisplayComponent />

<ButtonComponent />

</StateContext.Provider>

</DispatchContext.Provider>

Now, ButtonComponent only consumes DispatchContext, which (if dispatch is stable) never changes. It won't re-render when state updates.

7. Importance of Immutability

React relies on shallow comparison. It assumes that if the reference is the same, the content is the same.

If you mutate an object directly (obj.prop = 'new') and pass it as a prop, React won't know it changed. It will bail out of rendering, and your UI will be out of sync.

This is why you must always create new copies of objects/arrays (using Spread syntax ... or libraries like Immer) when updating state.

Immutability is the contract you sign with React to get predictable rendering updates.

8. State Colocation

A simple but effective rule: "Keep state as close to where it's used as possible."

Don't put everything in a global Context or Redux store if only one component needs it.

If a modal's isOpen state stays inside the Modal component (or its direct parent), toggling it won't re-render the entire App.

Push state down the tree. It naturally reduces the "Blast Radius" of a re-render.

9. Advanced Profiling Techniques

How do you know if you succeeded?

9.1. React DevTools

The standard tool. Enable "Highlight updates when component renders" in settings.

If you see a green/yellow flash on a component that shouldn't change, investigate.

9.2. "Why Did You Render" (WDYR)

You can install a library called @welldone-software/why-did-you-render.

It monkey-patches React to log to the console when a component re-renders unnecessarily.

It will print: Component Child re-rendered because of props changes: onClick (function value changed). This is gold.

10. Q&A: Rerender Myths

Q: Does key prop prevent rerenders?

A: No, the key prop is used by React to identify which items in a list have changed, added, or removed. While it helps React reconcile lists efficiently, it doesn't prevent a component from re-rendering if its parent renders. In fact, changing a key forces a component to unmount and remount (destroy and recreate), which is the most expensive operation.

Q: Should I wrap everything in React.memo?

A: No. Memoization has a cost (memory to store previous props + CPU to compare them). If a component is simple (like a button or a text label), the cost of comparing props might be higher than just re-rendering it. Use memo only for heavy components or those that re-render very frequently with the same props.

Q: Is Virtual DOM slow?

A: The Virtual DOM is fast, but it's pure overhead. It's faster than the Real DOM, but slower than "Svelte" or "SolidJS" which compile away the Virtual DOM. React's performance is "good enough" for 99% of apps, but you must avoid unnecessary work (renders) to keep it snappy.

11. Conclusion

Performance optimization in React is a fine balance between code readability and speed.

Start with clean architecture (Composition) and State Colocation. Then, identify heavy components using the Profiler. Finally, apply memoization surgically.

Don't be afraid of renders; be afraid of expensive and unnecessary renders.

With the upcoming React Compiler, many of these concerns will vanish, but the fundamental understanding of the Virtual DOM diffing algorithm will always be a superpower for a frontend engineer.